In 1965, when Dan Graham confronted the ideological implications of the proverbial 'white cube' he acknowledged the potentially exclusionary nature of the gallery: its physical limitations, curatorial agendas and economic imperatives. Art practice, he claimed, should 'resolve the contradictions [between art and the gallery] by bypassing the gallery structure altogether'. While artists, such as Marcel Broodthaers and Michael Asher, have done much to disrupt the institutional regulation of art, one Sydney-based collective – the Network of Uncollectible Artists (NUCA) – has engaged with artists and viewers who do not necessarily embrace the traditional parameters of contemporary collectibility and connoisseurship. The result is an artistic grassroots movement that both corrosively critiques and cleverly manipulates the conventions that might otherwise eclipse works by the project's self-described explosionists, noxious weed celebrationists and obsessive stickerers.

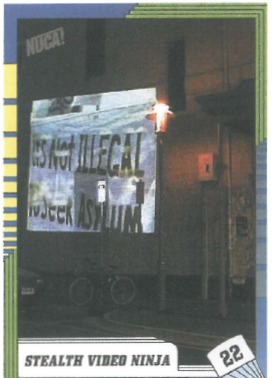

NUCA began by circulating a call for submissions, in which practitioners and aficionados could submit their top picks for 'ephemeral projects, participatory experiences, illegal art actions and activities that oddify everyday life'. By brainstorming the restrictive criteria by which art is conventionally judged, NUCA established a fresh continuum of characteristics by which contributors' works could be evaluated: authored vs. anonymous, apolitical vs. political, material vs. immaterial, done-for-money vs. done-for-love. In keeping with batting averages printed on baseball trading cards, each contributor's work receives a NUCA rating out of a possible score of 100. Sold by NUCA vendors wearing grey trench coats and infiltrating the venues associated with the 2004 Sydney Biennale, the cellophane-wrapped packs of collector cards provided a potent alternative to the festival's more normative and normalising elements: overpriced catalogues, restrictive thematics, and blowout budgets. Significantly, NUCA accomplished what the Biennale could not: a unique exhibition of politically edgy work that resisted the diluting and homogenising influences of bureaucracy and institutionalisation.

NUCA not only cherishes the placelessness, illegality, absurdity and experimentation that underpin many contemporary works (or others' subsequent rejection of them), but also acknowledges the crucial roles that viewers play in making art 'happen'. These roles, however, are assumed at a cost, as individuals plunk down $2.50 for each opportunity to build their collections. Gone are the days of Felix Gonzalez-Torres' works that initiated rituals of gift-giving; in their place is an anti-aestheticised culture of wheeling and dealing that appeals squarely to punters' desires to barter and acquire.

When I attended the inaugural opening of NUCA's collector card sales at Sydney's Hollywood Hotel, the evening quickly transformed from an opportunity to learn about some of Australia's most creative artists into a desperate free-for-all to obtain those cards missing from my collection. Although the event exposed the fetishism that can ultimately corrupt the critical eye, it also forced attendees to step outside their comfort zones, to interact with people they might not otherwise approach and to massage hardcore hoarders into giving up their stashes.

Ultimately, the viewer/consumer's desires to possess proved ancillary to the ideas impelling the more memorable works in NUCA's project. Among them is Bec Dean's installation of several variable message boards that flashed eulogistic texts from survivors who lost loved ones to HIV/AIDS. Normally warning of road hazards and traffic conditions, the signs placed in Perth's Robertson Park served as an ephemeral memorial – distinct from the materiality of other projects, such as the AIDS Quilt, and unique in terms of the signs' re-negotiated sense of purpose.

Such interrogations of materialism and viewer/object relationships are more pointedly reflected in works, such as Christian de Vietri's in(security), that force 'art' to undergo the ultimate disappearing act. The installation consists of fifty security guards – procured with de Vietri's artist's fee – whose task was to patrol the gallery, 'protect' the artworks and keep a close watch on visitors to the exhibition. Since the guards themselves constitute the artwork, de Vietri's installation draws attention to both the power imbued in scopic relationships and the persistence of viewers' object-focussed expectations within gallery environments.

Perhaps NUCA's most extreme foil to the gallery and material culture is the National Iconoclastic Lobby Group (NILG), which 'calls for the destruction of images everywhere' and angrily protests 'the wastage associated with outdated modern art museums the world over'. Unflinchingly motivated by a belief in viewers' integrity and their ultimate ability to fashion their own histories of art, NILG convincingly declares that 'memory is our only museum'. While conventional galleries might disagree with their mission, NUCA's ongoing project serves as a timely forum for those artists whose works confront and subvert the institutions that all too frequently ignore them.