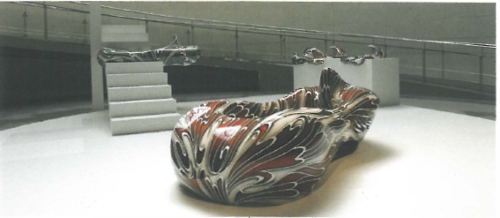

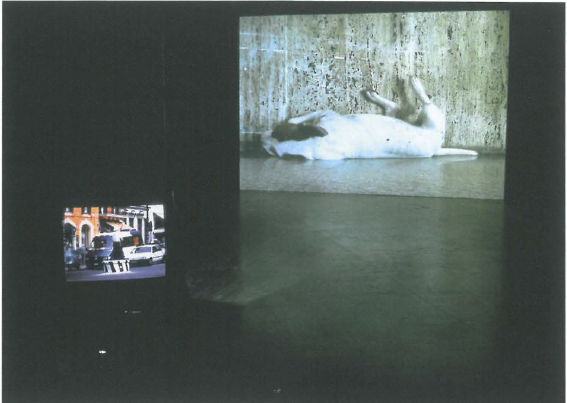

When viewing Artificially Reconstructed Habitats it's worth bearing in mind that before Finola Jones' wide-ranging career as an artist began she once worked as a window-dresser for a department store. I mention her early training because of the finesse with which this complex 22 channel video and sound installation has been arranged in the habitat of the Canberra Contemporary Art Space. Monitors of various sizes concurrently play video footage of humans and animals filmed in urban environments around the world. These are displayed at different heights in clusters – configurations that evoke social groupings themselves – and are further flanked by two large projections, one of a dog fast asleep at Stationzale Centrale Napoli, the other screening underwater footage of penguins and ducks from the Berlin Zoo.

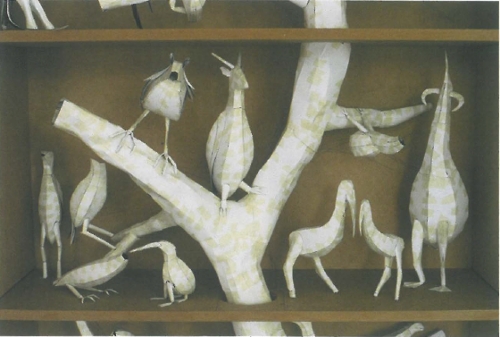

Jones is not a video artist per se; she identifies with the conceptual art notion that 'the idea dictates the medium' and has worked across many media from sculpture to performance-based work. The idea for Artificially Reconstructed Habitats emerged from an earlier video piece, More Major Mammals, made while an artist-in-residence in New York and exhibited in Dublin. Faced with the problem of a restrictive workspace, Jones taught herself to shoot and edit video inspired by TV footage of an underwater hippopotamus swimming in its zoo enclosure. Something about its high meniscus line recalled the colour fields of a minimalist painting.

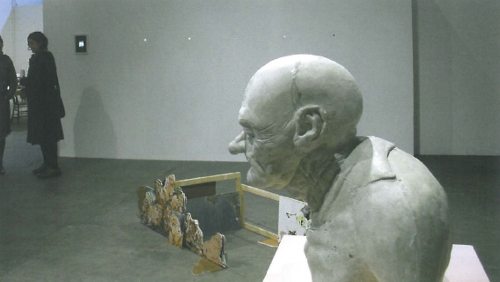

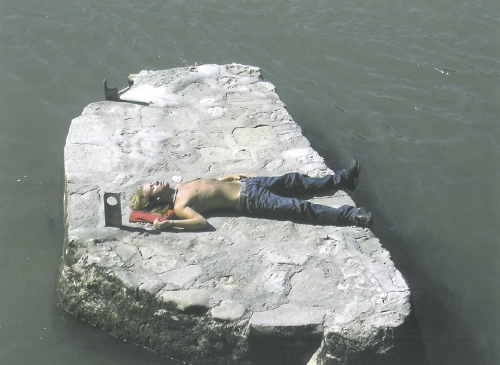

The cramped conditions that generated More Major Mammals stimulated Jones to 'look at animal behaviour in unwilling confinement and human behavior in willing confinement'. It's an idea that animates the show beyond purely subject and theme. Her subjects are filmed in long takes, using predominantly stable, fixed camera set-ups that restrict contextualising information. In the footage of the sleeping dog, for instance, his slumbering form fills the frame for close to twenty minutes; flickering shadows on the marble floor and loudspeaker announcements provide the only clues to the animal's environment. It's a technique that provokes both curiosity and anticipation.

Furthermore, Jones has selected footage that resonates across monitors, relying on the repetition of gesture, framing (a penchant for horizontal compositions) and sound to unify the work. Hidden behind a partition is the humorous slow-mo TV footage of a UK Big Brother contestant, Sandy, jogging laps in the swimming pool while whistling the theme to Star Wars. It merges in the gallery space with bird song emanating from another monitor. Jones invites us to notice the similarities between man and animal – the swimming ducks on one monitor, and Big Brother contestant on another, man and bird both in song.

Despite its many if simple pleasures, it's difficult not to feel somewhat uncomfortable with the bleak but cloying premise that underlies the exhibition. Jones' camera and installation not only anthropomorphises but aesthetisises the animals and their enclosures. More interesting is the way in which Jones' passion for travel has intersected with her compulsive collecting of things. The 'moving snapshots' of Artificially Reconstructed Habitat were taken while travelling and as a resident in various international cities. This exhibition offers an insight not only into confinement but also the global labour force of contemporary and Jones' own unrestricted mobility.