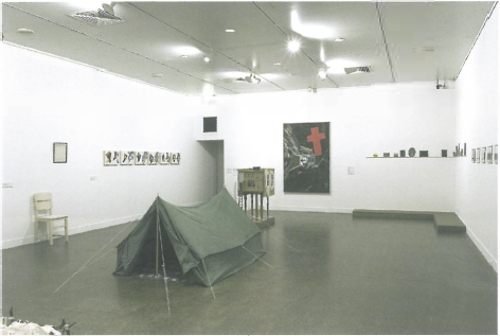

If Australia's nationhood is grounded upon a contested history, one that the postcolonial theorist Helen Gilbert has described as 'marked by gaps and ruptures', then the physical landscape itself can be seen as ever-marked by this tension. This idea is explored by Jo Darbyshire in her exhibition Ghost River Paintings, shown recently at Span Galleries in Melbourne and Gallery East in Fremantle. Using the realm of water to de-anchor the murkily buried knowledges that contest dominant histories, Darbyshire's specific interest is in the river, in particular the lifeblood of Perth city, the Swan.

It is a subject not unfamiliar to representation - you only have to see a panorama postcard of the city's shiny boats on shiny waters to glimpse the beating heart of the metropolis. And it's been a long time beating out identification, with the colony's very location chosen for the river's use as a highway to the inland for early settlers. However Darbyshire's landscape paintings point to beneath the river's surface, to the narratives of darknesses that have been smoothed over in the development of the 'City of Light'.

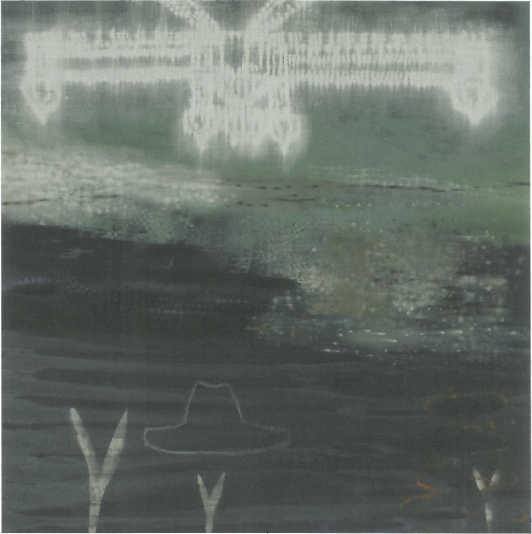

In a number of works, site-related landmarks from different periods in history are presented suspended within a watery underworld. In The Victorian Baths, a bathing pavilion that operated in the 1900s hangs swimmingly, submerged within mottled depths. Within Pièce de resistance, arches of flickering streetlights that commemorated a 1954 visit by Queen Elizabeth are glisteningly revived.

The result is an ethereal shrine to colonial markings upon a landscape, which in turn hints at the battles of occupation that remain unmarked by commemorations, the historical gaps that are generally unacknowledged – that this river was not an uncontested acquisition. The fraught human layers of this abject underbelly are also intimately personal for the artist, not just as an inhabitant of the city, but by her great-aunt's suicide in this river on Mother's Day in 1974.

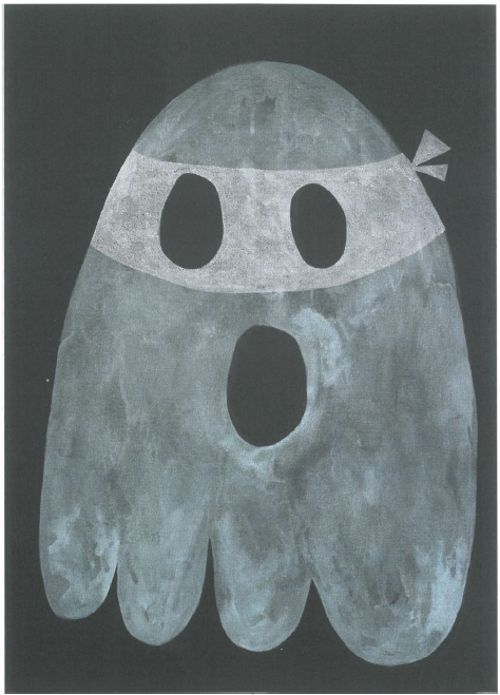

The positioning of the landscape as a cultural production is reflected in the structure of the paintings, which give the sensation of being within the water looking up and out, peering through immersive depths. Structural clues of architecture, swathes of light and obscure objects are combined in a way that intersect and intertwine. Squint your eyes and the Baths could be silky reeds or paperbark trees, the glossy phosphorous patterns in the striking Two-up could be fish scales or lights. A repeated jellyfish shape appears organic until closer inspection reveals that it has been made using a doily as imprint, suggesting a lost world of feminine ritual and colonial production.

In The Victorian Baths the use of a heady teal offers a rare glimpse of romance, a familiar signification of water as-we-want-to-know-it, sun-blasted and pure. The effect is dizzying and gives a rare, comforting feeling of knowable waters. But this is a tease – in the others, fluorescent shades glow unsettlingly, set evocatively against dense pools. It's pretty clear that you could drown in here.

Darbyshire's method of building up cumulative layers of stains, washes and imprints features a blend of oils with gum from the Marri tree, with its own blood-like associations, signalling an engagement with place again marked by the question that underscores the exhibition: how to identify with an unresolved landscape?

While offering a dip into a recuperative project of unearthing buried knowledge in relation to a specific location, the artist employs an interesting tactic of diversion. It's never really clear, even from the catalogue, which specific stories are referred to - instead we are just given ghostly clues. The catalogue universalises themes of humans and water, with text from sources ranging from Bachelard to Flinders. But while this approach might appear to conflictingly muddy specifics of location, it actually works to galvanise the viewer into a position of action - urging us do our own peering, to shine lights a little harder upon the gaps and ruptures, to what lies beneath.