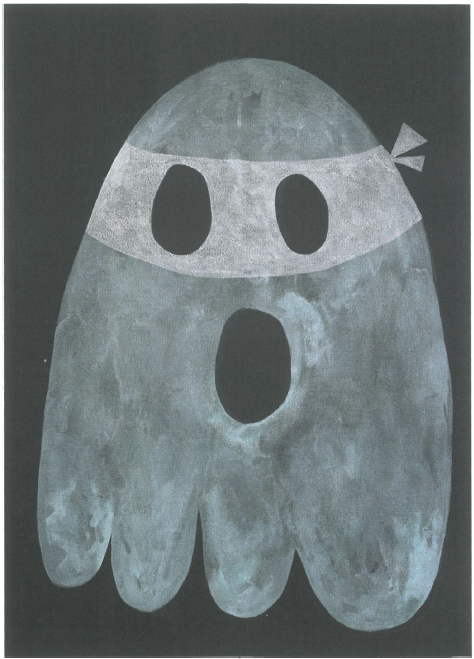

The defining image in Nell's Happy Ending is called The Ghost Who Walks Will Never Die. For those steeped in the Western tradition of comic strip superheroes this conjures up images of the Phantom, dweller of the Skull Cave. However Nell's ghosts belong to a different culture, both more recent and more distant than American-influenced Western pop in the mid twentieth century.

The image, as stark and simplified as any Ned Kelly mask by Sidney Nolan, is a riff on the graphic style of computer games such as Pacman, which in turn come from the kind of nature spirits who inhabit the forest in Hayao Miyazaki's Princess Monomoke. It is not a hostile image, it is even friendly. This ghost is a creature that it might be good to meet at times of uncertainty, transition, or death.

Nell's is an exhibition about what happens when it all ends in violence, and young people die. She is making an attempt to find a new visual language to show what might lie beyond the place where life turns violent and flees young bodies without a visible trace.

The central piece, Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again? is a sculptural memorial to people, usually adolescents, killed by car. Nell claims that this is based on memorials she sees as a part of the culture of the roads near her childhood home of Maitland, near Newcastle. Despite her claims, roadside memorials are not solely a Hunter Valley phenomenon. The flowers in the whisky bottle, the roadside cross, are familiar to those who drive Australia's roads. Flowers are often taped to telegraph poles at the point of death, or piled in mounds on suburban crossroads. Nevertheless, this piece is an important commentary on a modern cultural phenomenon. It is only in recent years that spontaneous shrines have been made at actual sites of Australian road deaths. It is all a part of the cultural shift towards celebrating death and possible spirit worlds that took place at the end of the materialistic twentieth century.

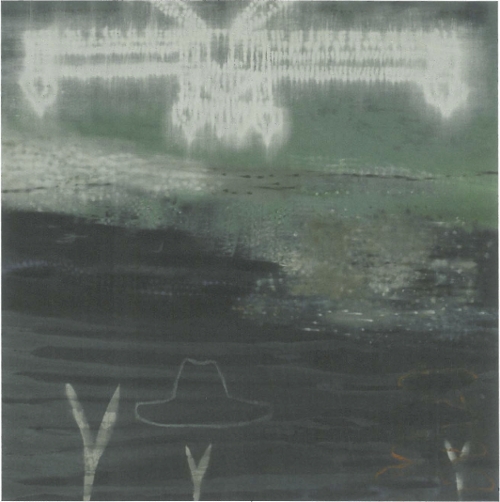

These young ghosts (and too many of them are young) haunt the roads of the world. Nell draws these as ectoplasm, hovering above the memories of the accidental dead, hovering in a neverland of iridescent colours and metallic paint.

With their intense matte background these images exist in a zone of heightened intensity of colour. Their flat forms cite the graphic style of sci-fi magazines, with their fantastic shapes and organic forms. Absurdly, the intensity of this tonal contrast also recalls the whimsical drawings that decorate inner city cafe menus, which is fair enough as Nell is attempting to construct a visual mythology to deal with the grim realities of young death and elaborate mourning. So Guardians of the Eastern Dark reveals a fantastic multi-headed creature to guide the way, and a sperm-like big-headed organism, weeping tears from its very body, while Come As You Are implies a party mood in hot pink.

It is hard enough to deal with death, and nigh impossible to cope with the relentless meaningless deaths of young people on cruel roads. Memorials and mythologies have their purpose here, in making sense of the senseless, giving comfort to the comfortless. Trying to say that bright spirits might arise from the ruined crash of the fluoro turbo-drive car on a black road in darkest night.