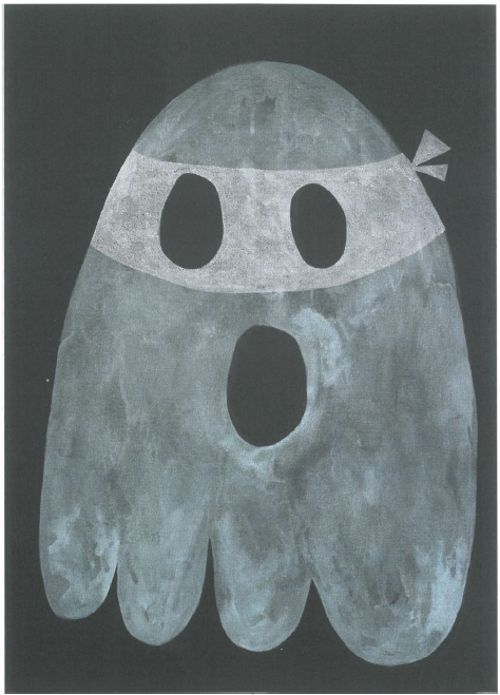

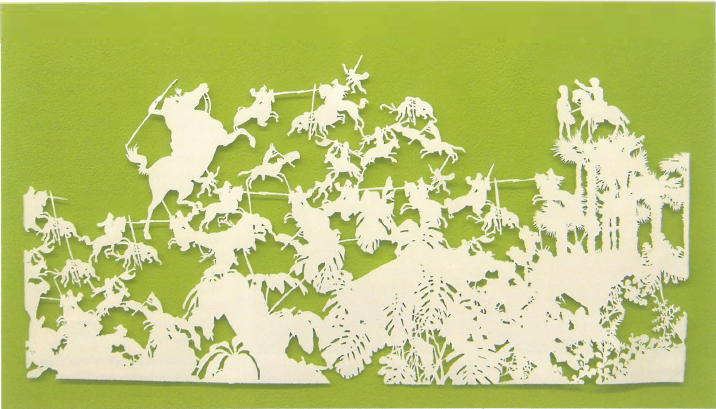

The lives and frequently gory deaths of the saints form the basis of a series of new works by Melbourne artist Emma van Leest, in the exhibition December Saints. One need not be well versed in medieval scripture or folklore to be touched by these works in paper, for their strength lies in the way they tell stories with simplicity and a strength which defies their beautifully minimal means of expression.

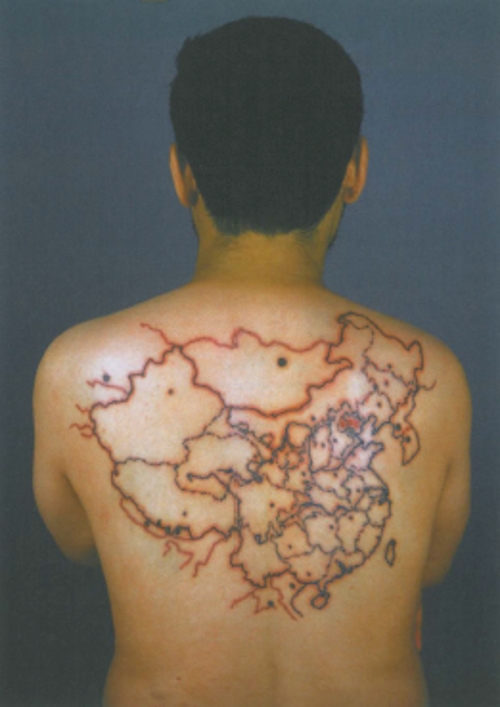

Van Leest's laborious art-making process is descended partly from women's handiwork traditions. Like knitting or stitching, the process by which van Leest has restored life to these long-dead saints is about taking a methodical, meditative, artisan-like approach. The inexorable link this process shares with domestic craft-making, as a vehicle for expressing deeper artistic concerns, feeds its symbolic fertility and ripens its potential to subvert. The paper cut-outs become lace-embellished fetish objects, which crawl under your skin and invite all other dispossessed art/craft forms in for the party.

Having initially employed paper to investigate the effects of light and shadow within a two-dimensional construct, December Saints now sees van Leest couple her craft with a narrative force, which acts to ground the work even more firmly in the literal. This is done by quoting directly from a variety of source material, such as medieval and classical children's book illustrations, and horticultural imagery. Starkly silhouetted but intricately picked out, the figures dance and play like puppets on a stage, where the gallery becomes a scaled-down theatre set.

The immediate impression is of Hans Christian Anderson-like frivolity, but like all satisfying and absorbing art the work takes on different meanings on closer inspection. The saints are being merrily decapitated, disembowelled, hacked down and dismembered. The marriage of extreme violence and beauty, found so commonly throughout Western culture, is rescued from cliché and flippancy here by the sheer volume of obsessive labour. The violence and beauty in the narrative is absorbed into the flatness of the work with the same nonchalance as the formal elements of light and shadow. The grief or pleasure found in the work by the viewer is therefore something brought to the work. Before you know it, you are engrossed in your own reactions to what on the surface appear to be very self-absorbed elegies to classical mythology.

In many ways van Leest's work defies categorisation; however it is surely emblematic of a growing interest among young Australian artists finding and expressing meaning through imagery which inspired wonder in childhood. As reflected in Ricky Swallow's paean to his fishing village boyhood, Killing Time, artists today are using less pastiche, and more homage, to extol the virtues of a time when simple delight could be found in the everyday motif, and to reflect on the changing nature of value sets and broader cultural meaning.