'Never judge a book by its cover', goes the old adage, and so it is with the cover of KaltjaNOW: Indigenous Arts Australia, edited by Ian Chance. On the cover, an Aboriginal woman is posed in profile with what looks like a Western Desert acrylic painting wrapped in the style of a possum-skin cloak, around her shoulders. This rather tacky image is reminiscent of those insidious early colonial postcards that we so detest, yet surreptitiously admire without ever really knowing why. But it is inside where it all counts, the meat around the bones so to speak, that holds everything together. Or does it?

Intended as a magazine-style publication "of what we hope will develop as a series of annual occasional publications from Tandanya", (From the Board of Management of the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute – Tandanya, the Preface p.vi), "KaltjaNOW is a collection of nineteen essays written mostly by Indigenous Australian authors, with others by non-Indigenous writers 'closely dependent on Indigenous sources".

The work of Indigenous photographers is featured strongly and several essays comprise translations of individual artists' own stories. Topics include insights into their work practice and their lives, such as with Janis Koolmatrie's fitting homage The Ngarrindjeri weaver to master artist Yvonne Koolmatrie, beautifully complemented by Agnes Love's photographs. Anita Heiss in Who's been writing Blak? offers a belated plug for Indigenous literature and a convincing plea for an increase in Blak writings of "our stories, our histories, our visions of the future" (ibid.: 144), as more of our elders pass on the further we move into this new century.

Curator Franchesca Cubillo outlines the cultural context for and the eventual re-discovery of "The remarkable Kundu masks of the Nyangumarta" in her most informative essay. However it is way too short and one gets the sense that this piece has been 'chopped and changed' and seems to have been over-edited for brevity. Sandra Phillip's A child's Dreaming, helps us to successfully sort the gold from the dross among the many illustrated children's books purporting to be based on Indigenous stories. She provides clues about how to 'judge' them, along with a well-researched bibliography of children's book titles. Michelle Torres talks to Alexis Wright in Cinema song woman, but one is left wanting to know more about this artist and visual story-teller from Broome in this all too-short piece. Selective editing is evident throughout KaltjaNOW with some pieces being too long and others inexplicably short.

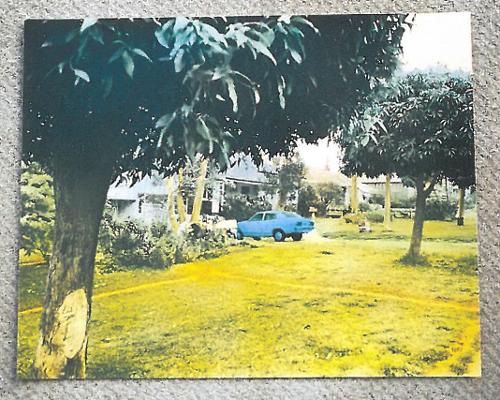

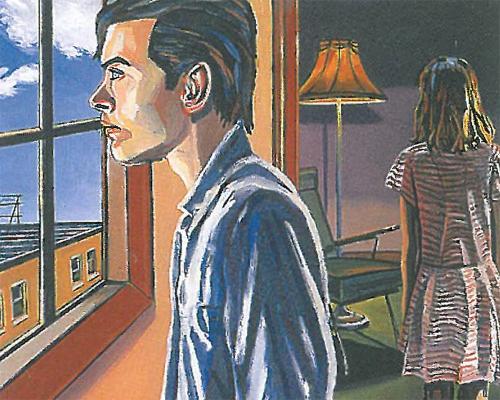

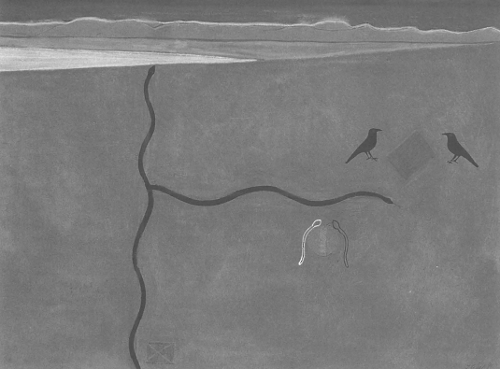

It is the photographs of the Indigenous photographers in KaltjaNOW, which are a standout for this reviewer. The late artist and photographer Kerry Giles and Fred Nam's photo essay Native orange country captures the beauty, grandeur and spirituality of the Adnyamathanha landscape in the northern Flinders and Gammon Ranges. Mervyn Bishop's colour portraits of senior Pitjantjatjara custodians in their country in and around their Angatja homeland community are also worthy of special mention. As well as the aforementioned images by Agnes Love most of the photo illustrations throughout KaltjaNOW are superb and well-chosen. The same could be said for the book's production values.

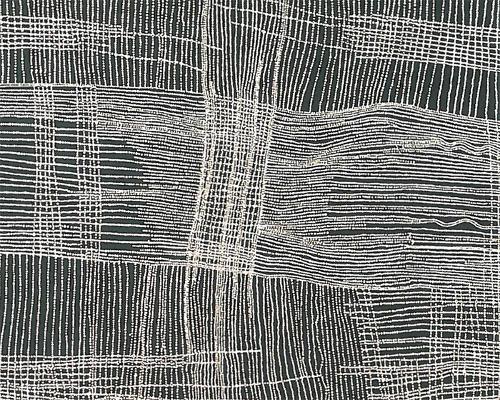

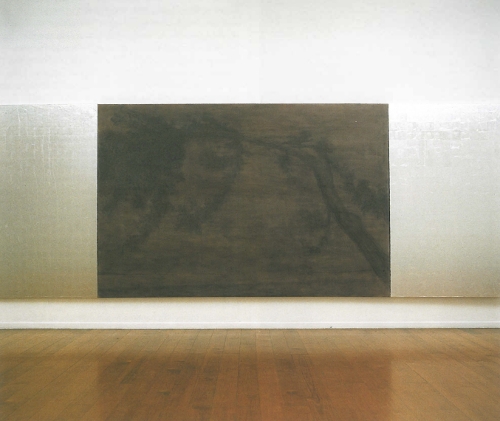

Can the same be said for the essays? The excellent pieces by Hetti Perkins, From genesis to genius and The international artist, and Diane Moon's Carried lightly, have all appeared before, and while there's no disputing their relevance or authority, one can't help wonder why these two very informed curators weren't invited to contribute other pieces instead? This publication started its life in 1995 so there must have been enough time to commission authors of this calibre. Yet many pieces are too short and others too long while some have been totally assimilated. This brings me to the translated artists' stories that promised so much and yet are a disappointment. In Painting up big – the Ngurrara canvas six members of Mangkaja Arts in Fitzroy Crossing talk to Pat Lowe about their art practice, and their making of the five by ten metre Ngurrara Canvas. This remarkable painting is also a title document to their lands in the Great Sandy Desert, yet their stories and their language has been re-written and Anglicised. This begs but one question – Why? The Walmajarri and the Wangkajunga language of these artists has been translated into 'correct' English, sanitised, which for this Aboriginal reviewer is both irritating and disrespectful. You have to wonder why a Walmajarri/Wangkajunga text wasn't provided along with an English translation?

This assimilating of Aboriginal language finds its worst expression in Kathy's story. The inspiring life of Pitjantjatjara video and documentary maker Kathy McKenzie and her story of the pivotal role in the early days of EVTV – Ernabella Television, is severely diminished because her speech has been 'adapted'. The bastardisation of Aboriginal languages in KaltjaNOW, as in this essay, detracts from the Indigenous voices throughout this publication. If the purpose was to make the stories more 'understandable' or accessible, then it has failed. There are no reasons today why this kind of authorial text-intervention needs to still occur and yet here is a prime example. KaltjaNOW doesn't quite live up to its promise "in, short, to provide a great read", although in its second promise that it will "display some great images" (ibid.:vi), it certainly does.