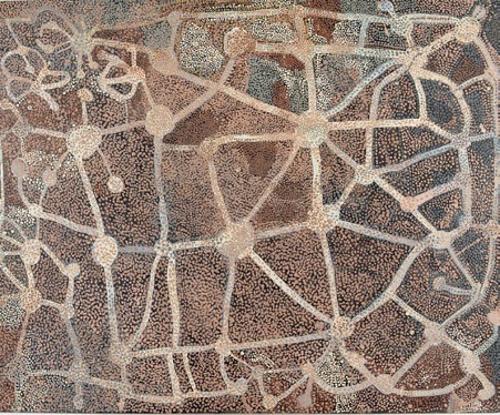

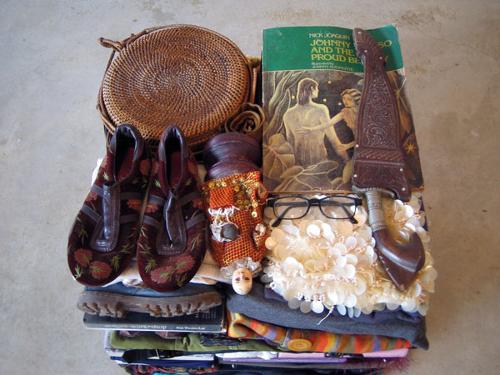

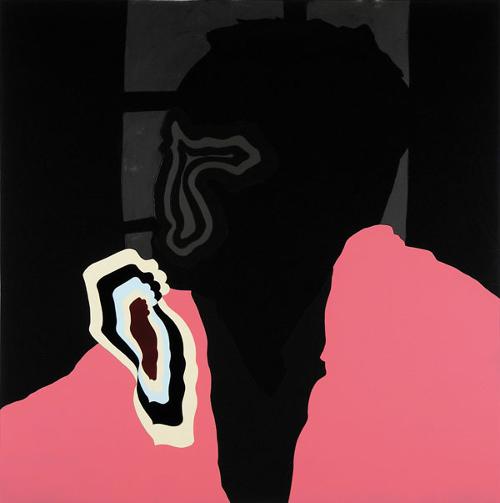

Juan Davila: Queering the South

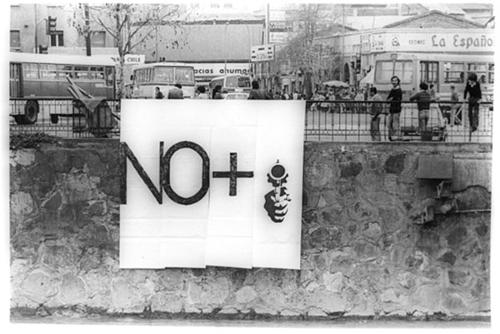

Juan Davila's recent retrospectives, held in Sydney and Melbourne, affirmed the astonishing array of historical, political, artistic, and cultural references populating his oeuvre since his move from Chile to Australia in 1974. As Davila explains:

The circumstance of living in two extremes of the world, in two peripheral cultures, slowly forced me to look at the materiality of the circumstances where artworks operate

. This text examines the work of Davila as being, in libidinal and critical measure, queer, and the extent to which this provides a signifying key to the artists TransPacific vision. The term queer is not merely called upon as one bound by its sexual connotations but as one used to describe a generalised sense of deviation from normalcy, within which Davilas work is here positioned. Specific works examined are: The Arse End of the World, Fable of Australian Painting, Retablo and Our Own Death amongst other key pieces.