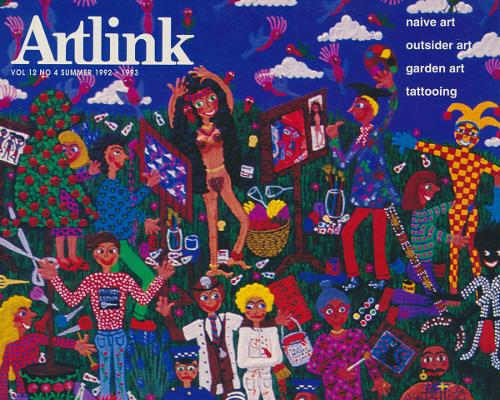

QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection is a sprawling hang split across all seven galleries of the third floor of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) International. It is the largest queer exhibition ever staged at a state gallery in Australia, consisting of approximately 400 works from antiquity to the present including fine art, fashion and design. The exhibition was brought together by a curatorium of five internal curators: Ted Gott, Angela Hesson, Myles Russell-Cook, Meg Slater, and Pip Wallis. QUEER doesn’t attempt to provide a definitive history of queer art—that would be impossible, especially given the historical limits of the explicitly queer content in the NGV’s collection—instead the central ambition of QUEER is to explore the NGV collection through a ‘queer lens’. Divided into several loose thematic groupings that bleed into each other, the list of artists is so vast it is impossible to succinctly survey: Andy Warhol, Vivienne Binns and a Grecian vase from 540BCE are included in this broad church. After all, QUEER is a collection hang, where the imperative is to ‘get it out and show it off’. This is evident in the crowded exhibition design, a not uncommon result of collective curatorial visions, especially one that is attempting to satisfy intergenerational and diverse queer communities. In QUEER, design interventions are minimal: no mirrored walls or architectural interventions typically associated with the NGV’s major exhibitions. The lack of pizzazz that one might expect from a queer celebration leaves it feeling a little straight. Accompanying the exhibition is a 628–page publication with over sixty texts, and like the exhibition the catalogue surveys queerness not only though expressions of identity but as a politics, a sensibility, and an aesthetic movement.

Because QUEER is so tightly woven and ambitious, it is difficult to untangle. What I intend to do here is explore the exhibition through its curatorial framework and extrapolate the relationship between queerness and the NGV as an institution. Queer people are no strangers to the proliferation of corporations capitalising on the success and popularity of queer politics. The principal sponsorship of QUEER by American Express is a case in point, given the company actively supressed a garment included in this exhibition from appearing in the film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), but are now happy to bankroll the exhibit. Unsurprisingly, the accompanying didactic for Lizzy Gardiner’s gown of gold credit cards makes no mention of American Express’ original actions. There are a multitude of examples of complicated relationships between queer culture and commodification that run throughout QUEER—none more obvious than themed merchandise in the gift-store. More on that later.

The first ‘corridor’ room in QUEER addresses the origins of the LGBTQIA+ rights movements, its entry emblazoned with the exhibition title in huge letters. We are greeted by Gilbert Baker’s now ubiquitous Rainbow flag designed in 1978, followed by a digital display of David McDiarmid’s Rainbow Aphorism series from 1993–5. McDiarmid’s works are one of the most iconic Australian inclusions throughout the exhibition, in part a legacy of his survey exhibition at the NGV in 2014 (the gallery holds 103 works). McDiarmid’s aphorisms speak to the AIDS induced nihilism which Lee Edelman’s polemic No Future (2004) attributes to a generation of gay men defined by loss and death. More broadly the works in this space coalesce around the subject of how a strong empathetic gay community and aesthetic emerged from grief and mortality despite the hysteria surrounding HIV/AIDS which fuelled gay hate in the 1980s and ‘90s.

.jpg)

At this point it’s clear that gay liberation and its social implications are the predominant subject of this relatively small gallery space. Intermediately scattered throughout are works most associated with ‘gay (and feminist) lib’ 1970s-90s, with inclusions from Nan Goldin, Guerrilla Girls, David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring and others. Ngāpuhi/Māori artist Ross T Smith’s L’Amour et le mort (sont la même chose) (1990-92) is a standout, consisting of black and white prints cut up and adhered to a sheet of aged plywood. The prints depict an abstracted nude male figure strewn across the panel, made at a time when gay intimacy and skin was rendered in the public realm as abject and sickly. Nearby, Ponch Hawkes No title (Two women embracing, ‘Glad to be gay’) (1973) is one of the rare instances in Queer that represents Lesbian intimacy. Hawkes’ striking images stand out in a room that prioritises the politics of survival from a queer/gay, male perspective. Alongside these late twentieth century artists are contemporary artists’ works that include Textaqueen’s Gandhi returns (self portrait) 2013, eX de Medici’s .308 (rifle) (2004), and Paul Yore’s recent The Evacuation of Mallacoota (2021). Yore’s work formally and conceptually acts as a conduit to the previous generation of ad-hoc, DIY activism, his stitching and collaging of intense imagery continuing a legacy of impolite queer politics. The artist’s work consistently pushes against the sanitisation of queer culture. For the most part, the thematic linkage between all the works in this room is a Western context of activism that has defined American, Australian and European queer practice: whether that be actual art-as-activism via poster making, photography documenting these events, or the aesthetic lineages of this intensive period. Despite the awkward hang, the constellation of works speaks acutely to the realities of making politically queer work either at the institutional peripheries—or when evoking the periphery from within the institution.

One of the key components of QUEER is the laborious and meticulous task of queering so many works from the collection. Anecdotally, this is one of the most divisive aspects among audiences—and they are many and varied opinions if conversations with friends, colleagues, and social media commentary is anything to go by. Here the NGV’s revisionist art historical strategy—by no means a new technique for a museum of this vintage and scale—can be easily read as overcompensating for the historical gaps in their collection of the missing work made by queer people that address queerness as the primary subject. The collection as it stands reflects generations of negative institutional sentiment towards queerness—especially evident is the lack of queer women and transgender artists collected. This is not a fault of the curatorium per se, but that of the institution they are contained by. The curators appear to have leveraged this exhibition to grow the collection in the future, specifically focusing on collecting works by gender diverse and queer POC artists—not dissimilar to the recently announced National Gallery of Australia’s Gender Equity Action Plan (2021-26).

.jpg)

The dense queering of works includes numerous antiquities, many works on paper that draw on a myriad of queer historical tangents. Spending time with these often intimate pieces can be a rewarding experience. At times it is exciting connecting the dots, akin to the work of an amateur detective making sense of who or what is queer. Standout examples are two adjacent etchings: Daniel Chodowiecki’s Frédérick II, King of Prussia (Frédéric, Roi de Prussia) (1778) alongside Giambattista Tiepolo’s The Banquet of Cleopatra (1744)—the original painting (not included in QUEER) is a prized possession of the NGV. In the wall text we learn about King Frederick II of Prussia, whose father introduced a law banning sodomy. At the age of sixteen Frederick II was made to watch his first lover burn at the stake. We then learn about the acquisition of Tiepolo’s painting via Count Francesco Algarotti, who later became a lover of King Frederick II. Like much of the other queered work in the exhibition this rich history is drawn from anecdote, personal relationships, and gossip: in this context the label further expands the complicated matrix through which the Tiepolo painting came into the NGV collection. There is also a queer potential of Tiepolo’s painting itself: the moment of anticipation before Cleopatra famously drops her priceless pearl earring into a glass of vinegar (to trump Mark Antony’s excesses), exudes a camp drama that is explored in the following rooms.

The most explicitly ‘camp’ themed gallery has a focus on the NGV’s decorative arts and design holdings, though they are not confined to this space, with ill-plonked mannequins in the most peculiar of places, albeit acting as a kind of thread. This eclectic, interconnected series of camp displays are bookended by two short videos by queer women of colour. Hannah Brontë’s Umma’s Tongue–molten at 6000° (2017) sees a cast of Indigenous female rappers call to a matriarchal figure of nature in the face of dystopia, drawing audiences into the space. Tourmaline’s Atlantic is a sea of bones (2017) is based on Lucille Clifton’s poem of the same name about the New York City performer Egyptt LaBeija. Both works, via different means, speak to a feminine black queer aesthetic and sensibility that is often appropriated by white queers—highlighting the under-recognised legacies of queer black people.

The most resolved thematic hangs in QUEER are the two galleries on the right wing. Here the internal politics of the works are consistently in resistance to the hegemonic systems the works are contained by. Queer space takes centre stage, from the intimate settings of home to cruising spaces, bath houses and nightclubs. Many represent site-specific queer experiences of time and space that deviates from the norms of heterosexuality, with implicit and explicit rejections of traditional notions of family and work life. The transgressive nature of bathhouses and public cruising spaces were for a long time one of the only ways for gay men to meet each other. The most tender of these depictions is Hoda Afshar’s Untitled #4 (2015) from the Behold series. The de-saturated image depicts topless male figures embracing in an undisclosed Middle Eastern bathhouse, behind these four walls the men re-enacted for Afshar their ability to embrace and participate in desire for others that is otherwise not part of their daily life—we are reminded that a permissiveness of sexual encounter is not a universal privilege. Contextually centring Afshar’s image in the hang foregrounds the geographic and racial disparities between different queer experiences including photographs and etchings that document gay beats and club life. A curious collection-omission is Scott Redford’s Urinal, Broadbeach (2000) or Urinal Surfers Paradise (2000) whose detached depictions of urinals at popular cruising locations speak to the anonymity of public sex. In addition to bathhouses and parks, public restrooms have and still play a significant role in cruising culture—you don’t have to walk far from the NGV to find one yourself.

In a generous room of its own, the immersive Moving Backwards (2019) by Renate Lorenz and Pauline Boudry is a proportional outlier in QUEER, its scale dwarfing every other work. Conceived for the Swiss Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the large-scale video installation complicates notions of backwards movement. Set on a theatre stage described as an abstract club space, a series of intergenerational queer people move in and out of the frame; their bodies at different times interact and dance together. The film is an awkward and joyful signposting to the critical importance of queer club spaces and the multiple temporalities that unfurl there. What is particularly resonant with this work is its evidencing of the politics of club spaces: not only their internal politics but also how political organising has historically come out of fringe sites.

Entering the fifth gallery space, a Virginia Woolf quote from A Room of One’s Own demarcates a literary theme, densely filled by numerous works plucked from obscurity. At the back of this menagerie sit some of the most controversial inclusions in QUEER. The thematic for this cave-like space is the historical persecution of gay sex and its representation through artworks in the collection. The works here are contextualised by wall texts, without which most audiences would struggle to interpret their meaning. An example is an illustration of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher resting one hand on an axe and cradling her own head in the other. Close by is a self-portrait by former NGV director James Stuart MacDonald (1922). In his role as a critic and in his directorships of the NGV and Art Gallery of NSW, MacDonald was notoriously conservative and anti-modern, so ostensibly deriding woman and queer artists as instigators of aesthetic decadence. The inclusion of works in this section brings up an interesting impasse for the institution. On the one hand it is important that these uncomfortable and horrifying histories—many resulted in the murder and execution of queer people at the hand of the state—are told. However, its imperative these stories are stated without giving voice to those in support of or responsible for these events. I question the purpose of seeing these historical works if they aren’t paired with artworks that actively critique them. For the most part, these historic works rely on didactics—the curator’s voices telling rather than showing. The exception is Bidjara/Chinese–Australian artist Christian Thompson’s Othering the ethnologist, Augustus Pitt Rivers (2015), evidence that self-reflexivity is a postmodern strategy embraced by contemporary artists, whereas the institutions older collection pieces do not adequately address these stories. That is, relaying the past comes via objects which are sometimes only tangentially or problematically related.

The left wing galleries offer the final statements and are dedicated to a contemporary understanding of queer, defined as a methodology that challenges hierarchical and social norms, clearly signposted with an Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick quote. Ironically, directly adjacent is a work by Chilean/Australian artist Juan Davila who, true to postmodern form and aversion for identity politics, explicitly rejects the queer label. As the wall label states, ‘Juan Davila rejects the application of labels to his practice and therefore the contextualisation of his work in QUEER.’ In a way this explicit rejection of queer is a little queer itself. In Where’s Mickey? (2002) Destiny Deacon (Kuku/Erub/Mer) reimagines Mickey Mouse in drag to reinvent and twist depictions of race, gender and sexuality. Deacon, whose work embodies both humour and tragedy, in this instance challenges stereotypical representation of queer Aboriginal people. Moving through these two galleries, representations of queer sexuality and desire is prioritised. Agnes Goodsir’s The Letter (1926), painted in Paris, is a warm portrait of her partner Rachel Dunn. Goodsir was known for tender portraits of other women that challenged normative depictions at the time. Nearby, Brook Andrew’s (Wiradjuri/Ngunnawal) S & D II (1997) reconfigures how cultural memory is imagined beyond the assumed heterosexuality of Aboriginal men from a settler-colonial perspective – a reading Queer invites for this celebrated work, and Andrew’s own revised artist’s statement can be accessed via a QR code. Reversing this racialised voyeurism, in the centre of the last room a dated-CRT monitor plays Tracey Moffatt’s short film Heaven (1997) (concurrently showing on a big screen in the 2022 Adelaide Biennial Free/State), in which Moffatt (along with six female friends), filmed clips of male surfers at beachside carparks in various stages of undress. The work alters the historically dominant male gaze from a queer woman’s perspective. In the context of QUEER, it becomes thrillingly homoerotic.

Leaving the exhibition there is the expected queer themed merchandise and paraphernalia, though QUEER merchandise is by no means on a similar scale to previous NGV Design stores. The NGV’s exhibition specific rainbow design is on everything from face-masks to tote-bags, here we experience the hyper mainstreaming and commodification of queer culture, indicative of the paradoxical position that LGBTQIA+ communities find themselves in. As queer politics progresses through vital gains in inclusion and visibility it has brought concessions to the socialist, anti-institutional, and community driven roots of LGBTQIA+ movements. The result is a normalisation of queer sexual practices in mainstream contexts. Retailing for $99 the catalogue is inaccessible to many, but the nuanced ideas explored in the texts represent the layers of scholarship and perspectives necessary to underwrite such a venture.

The ideas running throughout QUEER are heterogeneous—a particular concession to the politics of being queer today. The most compelling queer practices are anti-capitalist, anti-normative and anti-institutional. Moreover, the productive and generative capacity of embracing an anti-capitalist struggle and failure is a key contingent of a queer sensibility and way of being in the world today. The gift-store, sponsorships and framing of the artworks generate an uncomfortable feeling. That said there is still something joyous about QUEER; never have I seen so many works by LGBTQIA+ artists, speculative as some may be, in one place, and I might never see it again. I can’t imagine how I would have felt as an adolescent seeing giant posters advocating for queerness while moving around the city, and it is still moving.

There is a paradoxical upshot with this exhibition: on the one hand it is important and vital, giving visibility to many insightful artworks by queer people, especially Australian artists, but the mainstreaming of QUEER also feel at odds with its radical origins—prioritising pride over transgression. In trying to unpack its own relationship to queerness, the NGV’s QUEER is by no means a perfect exhibition, but maybe that exhibition can never exist. To expect any institution to fully comprehend and represent something as mutable as queer is a fantasy: by necessity, an essential part of queerness will always remain outside the institution.