I never saw art as being a safe thing. I know that exists but that's not something that involves me.

David McDiarmid, 1993

For people of a certain disposition and a certain age, David McDiarmid’s ACON (AIDS Council of New South Wales) posters were part of our exploration of sexuality and identity amidst the HIV/AIDS crisis during the 1990s. The large multicoloured muscular naked male bodies with symbols, acronyms and names scrawled across each limb: positives and negatives of grief/lust/fear/care provided a new language for a community to own its public health concerns, and a troubling and appealing depiction of much of our felt ambivalence surrounding sexuality. They, along with his massive and elaborate Mardi Gras floats, were the backdrops to the AIDS vigils of the 1990s; an intense time of shuddering grief and defiant sexual pride.

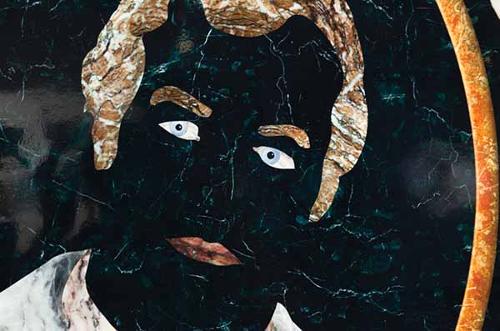

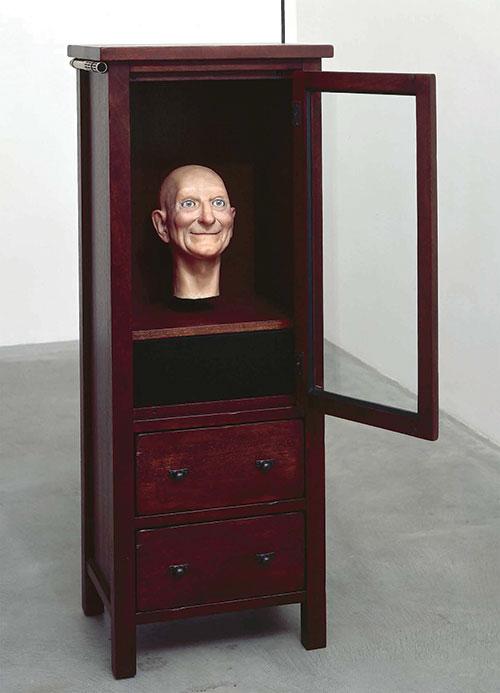

While best known for his HIV/AIDS posters and floats, the NGV retrospective of David McDiarmid’s art and activism demonstrated the extent and impact of over two decades of his work across sculpture, assemblage, printmaking, fabric design and drawing. The combination of sketches, notes and photographs with finished works indicate a consistent preoccupation with developing and expressing an aesthetic of camp; that could not only represent the lived realities of same sex desire, but generate a rich and relevant visual language particular to queer sexualities.

The appeal of McDiarmid’s work is far broader than the 1970s gay male subculture that he experienced in Australia and New York, and this is reflected in the arrangement of works in the retrospective. The galleries provide a chronology of McDiarmid’s changing approaches to gender identity and sexuality throughout his career. From quirky-kitsch formica tables, to holographic disco kwilts to his towering funeral poles comprised of anodised teapots and other domestic detritus, McDiarmid’s work develops an unsettling and enriching aesthetics of serious camp that creates a rippling effect of queer affinity. His 1970s works exploring the iconography of gay masculinity and the 'gay clone’ shifted quite dramatically to the 1994 DayGlo text screaming Hairy Dyke Seeks Cuntboy for Pussy Worship and showed why McDiarmid’s work exceeds the context of gay identity politics and AIDS activism from which it emerged. The selection of personal memoirs and essays in the exhibition catalogue provide an enriching reflection on his life and creative output.

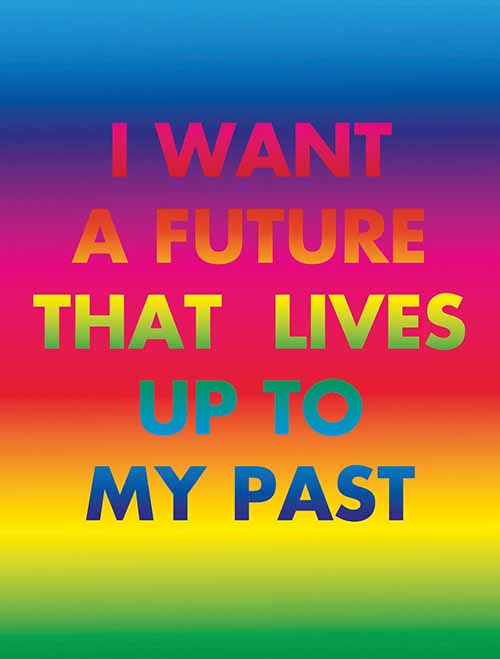

The profound queerness at the heart of McDiarmid’s oeuvre makes his work seem less dated than other exhibitions of ‘gay’ art. His retrospective coincided with two shows at smaller galleries in Melbourne based on images and files from the Gay and Lesbian Archives in time with the 20th International AIDS conference. Unlike black and white photographs sprinkled with glitter, or embellished with the legible trappings of camp, McDiarmid’s works are profoundly camp in their excess of signifiers, images, fragments and surfaces. This is a campness that extends the limits of the frame of a work, or the framing within a particular historical epoch, and is sustained from the stitching layers of leather, paper and images in his 1978 Man Quilt to the shimmering holographic mylar collages in the 1990 Kiss of Light series. In the NGV show, the Kiss of Light works were hung in a black passageway, as a prelude to the large room of Rainbow Aphorisms. Here the viewer’s reflection was broken and bounced around as infinitesimal fragments of light shimmered into a swirling mosaic where the blink of a holographic eye met our own eye at the centre of a muscleman’s proffered anus. This is not just a gayporn mosaic; this is a deeply compelling and affecting work. To behold it is to become embedded within its own plays of light and possibility.

McDiarmid’s work is not about the representations within his images, or simply slogans. It provides a complex layering and mashup of words, colours, textures, images, text, forms and shapes into a shimmering agglomeration of affects, sensations and possibilities. Sexuality is performed in his work as an oscillating compound of conflicting and contradictory emotions and possibilities: grief/love/hate/despair/lust and the hysterical deadpan carnivalesque of camp humour that creates a frisson of recognition, declaring: ‘This is what we are’. It hails those of us with bodies and desires that don’t fit or seem impossible or unlovable, and beyond words and images, the work shakes viewers and shocks us with its intensity, reminding us of life, lust, pain and defiance.