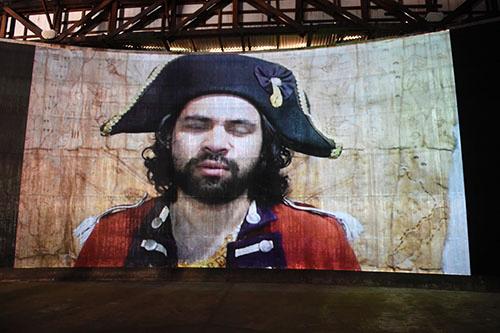

The art in Post-hybrid: Reimagining the Australian Self, curated by John Curtin Gallery's Collection Manager Lia McKnight, can be described in two ways. First, as counter-grotesque, as artists riff on the politics of Australian identity, playing on the anxieties that drive the country, and turning its grotesque politics back upon itself. The counter-grotesque art here includes Darren Siwes’s photograph of an Aboriginal couple wearing royal costumes and caked in make-up; Ryan Presley’s Aboriginal face on a Photoshopped Australian banknote; and Chris Pease’s dreary suburban plan scratched into floorboards.

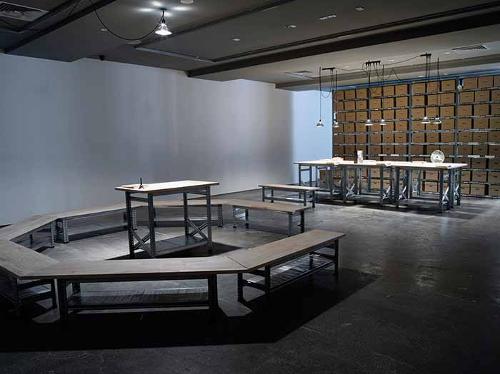

There are also works that turn this counter-grotesque into uncanny beauty: Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s floorboards with a prayer rug pattern cut into them; and Danie Mellor’s signature pastiches of porcelain blue landscapes, populated by naturalistic full colour animals and people. A second type of work in this exhibition is what we might call Australian materialism, which is work driven more by its materials than by representations. Little wire baskets by Lorraine Connelly-Northey hang from the ceiling, and Galliano Fardin has pressed rusty tin cans into wood. Here identity is sublimated into stuff, as these artists meditate on what the country is really made of, rather than advertising the horrors of its social order.

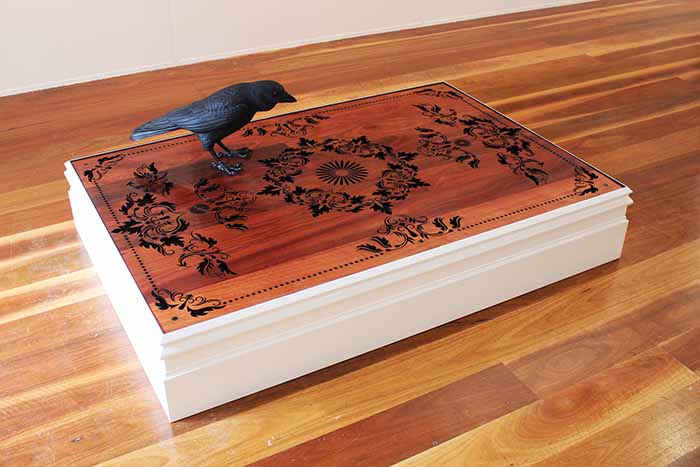

The tension between the counter-grotesque and Australian materialism is illustrated in work by the Abdullah brothers. Abdul Abdullah has produced a poster of his Muslim father with the word ASSIMILATE spelled out below, while Abdul-Rahman Abdullah has carved a wooden crow that ponders the meaning of laser-cut wooden floorboards. These works configure the tension of Australian materialism with the counter-grotesque, turning propaganda into the beatific and wood into contemplative beauty. The difference between these Muslim brothers can be explained generationally, growing up before and after September 11, as if the mode of one’s sublimation is decided at birth.

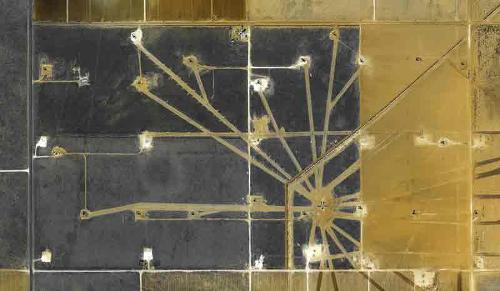

Amidst the constant play of identity politics in Australia, one wonders whether we are stuck at an infantile stage of development, or if the very concept of Australian art is tied to complexes that can never be shaken off. It is as if we are trapped in a cycle in which materialism remains irreconcilable Australianity. The formal questions that come with tin, wood and wire appear at odds with the grotesque force of Australian political life.

Among the works in the exhibition that are not caught up in Australianity, the painted aluminium busts of Indonesian artist Dadang Christanto more directly register the brutality of politics. Here the grotesque is redeemed, brought into beauty, with the fires of history burning inside. Christanto’s work pushes the problems of Australia into its region, as if the sublimation of political life is a condition shared by people in many places at many different times. In Christanto’s work there is no choice between representation and materiality, between the grotesque and the beautiful. For art to be effective, it needs to be charged with both, in a counter-grotesque materialism. And so, Christanto has Hindu gods dancing upon a hollow face.