the artist. Photo: Victoria Hunt

Contributing to a present focus on contemporary dance in the gallery context, 24 Frames Per Second critically engages with non-live work. The curatorial aim of Nina Miall and Beatrice Gralton, it appears, is to play with the installation of cross-disciplinary art that involves dance but that does not place the dancing body in the live space of the gallery. The conceit of the exhibition is the complex intersection between contemporary dance (and therefore choreography), video art and an expanded notion of installation for screen-based or projected media. Considering its scale – 24 works, commissioned over a three-year period, each installed differently in the enormous interior of Carriageworks – 24 Frames presents an opportunity to think about video art at a time overwhelmingly defined by screen technologies and mediated textuality.

Cross-disciplinarity is not the mere mixing of skills or habits, materials or methods. Cross-disciplinarity refers to processes of thinking and making that consider the specificity of different modes of practice, and can also be a way of emphasising difference in collaborative or collective work. All art in this hypermediated, information-dense cultural moment is multidisciplinary insofar as it depends on and produces networks and translations. But cross-disciplinary work makes its networks and translation both subject and object of its inquiry – aiming towards, more than anything, an emphatic approach to the constructive potential of difference-as-practice. The most exciting work in 24 Frames takes seriously the desire for cross-disciplinary engagement with contemporary art in a gallery space.

Khaled Sabsabi's Organized Confusion presents two floor-to-ceiling projections, each facing the other, showing looped footage of fans at a Western Sydney Wanderers soccer match. Making a square, these screens are matched by another two-part installation: on one side, small screens showing different stages of the same dance (performed by Agung Gunawan) and on the other side a plinth displaying the wooden mask worn by the dancer. The Wanderers supporters move their bodies in a way that is at once highly organised and spontaneous, a physical manifestation of collective intensity and intimacy that, despite its shared subject, is often read as the mass expression of individual loyalty and fandom. Not to belabour the contrast between public and private, individual and collective, spiritual and social forms of physicality, in this context the movement is read as a kind of dance, creating resonances between dance and that which is rarely called dance but which demonstrates an awareness of aesthetics, duration, rhythm and embodiment.

Brian Fuata’s Apparitional Charlatan comprises footage of his own performances (but with his body edited out), overlaid with text fragments that respond to dance films collected on Ubu Web (a digital archive of modernist and contemporary avant-garde documents). The text is a running commentary on the video collection – partly discussions of the works themselves, and partly appropriated language from the paratexts that accompany them. Fuata’s video examines the trace of dance in media archives; absent of an actual body, the work shows how the body is registered and altered via a variety of material translations.

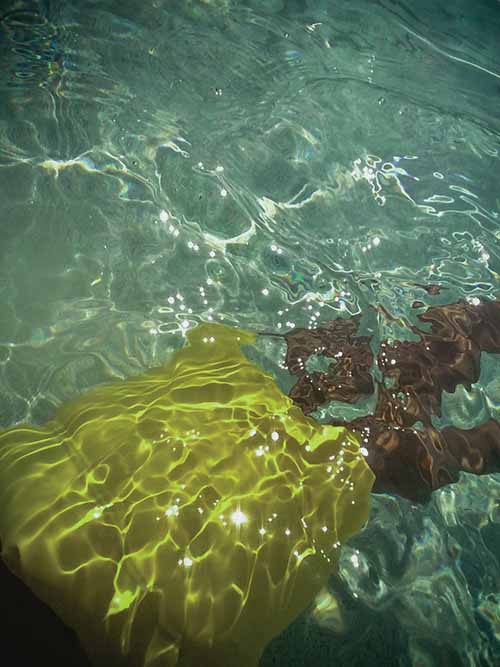

Repatriate by Latai Taumoepeau and Elias Nohra comprises a series of small screens, each at a different stage in a single channel loop that, over the course of an hour or so, presents a tank filling with water in which Taumoepeau, clad in flotation devices, adjusts to the changing depth and increasing buoyancy of her dancing body. The wall text discusses the vulnerability of small Pacific nations to the effects of climate change; the choreography traces a history of dance and gesture from across a number of Pacific Islands. The installation of this work in a small, narrow corridor with serial screens and a multi-looped but single-scene narrative affects a temporal urgency that emphasises the durational aspect of its eco-critical focus.

These works explore the specificity of video: the use of sound and its relative clarity in a mix; the use of editing and the possibility of single- or multiple-channel cuts; the projected or illuminated surface/screen and its variable light-show; the shortness or longness of a scene, loop; the ambiguity of scale or the clarity of detail, and so on. Such work departs from video as a documentary record of a dance performance or representational works in which dance is the narrative device.

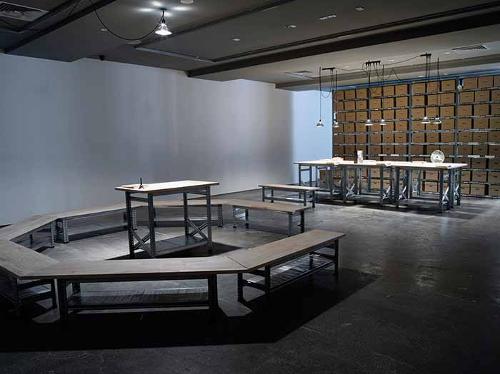

The exhibition occupies a massive, almost entirely dark space with two works (Sabsabi and Fuata) externally positioned at the entrance. Some works are installed as projections, some on screens, some in sculptural or object-focused assemblages, one in the small theatre at the edge of the gallery. Sound – an important element in every work – is either channelled through headphones or amplified locally. The ambient noise of the gallery is overwhelming, making the distinction between one or another soundtrack ambiguous. Negotiating the space is intense and, at times, difficult. Such an affective experience can be appreciated as a dislocation of habituated or passive art-viewing, and as a call to be especially attentive to the difference between and confusion of separate works, with the resultant disorientation and reorientation of the body in a highly-mediated environment.

The challenge of such a large-scale project begs some questions or alternative strategies: the works could have been shown in smaller groups over time or at different points in the commission or in non-physical sites as well as in the gallery. These questions and strategies add to the constructive debate around exhibiting film, video and performance art.