I was given a copy of the catalogue and it sat on my desk unopened for some time. The image on the front cover of a deer-like beast, its body pierced with wooden poles, trussed into a harness and hooded in black, provoked a feeling of apprehension. Although I had seen Julia Robinson's work before and appreciated it, I put off attending this exhibition as I feared that her practice had taken a darker, more sadistic route.

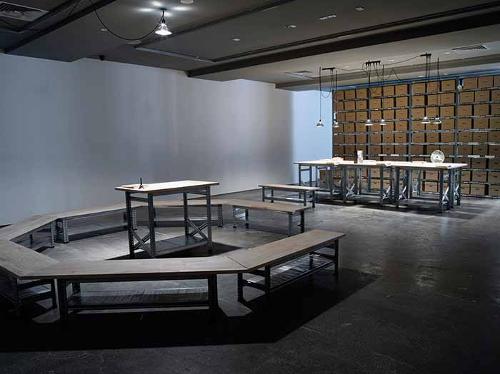

The sculpture that I feared, Folk Death, was the first work that I encountered on entering the darkened rooms of the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia. The wooden poles are more benign than the catalogue image conveyed; they don’t pierce or rip the skin of the animal, but are integrated into it, raising it like stilts. Although still a confrontational sculpture - the deer is anonymous and shackled in servitude – it is also curiously floating and elevated by its restraints.

Two sculptures in the large back room of the gallery are a departure from Robinson’s previous work in terms of colour. Here, her signature animal forms are highly ornamented. Rutting Creature 1 and Rutting Creature 2 feature grey soft-skinned creatures engaged in dances of copulation. The animals in Rutting Creature 1 are made faceless by diaphanous tent-like head coverings reminiscent of 17th-century royal tents in costume dramas. As in the childhood game, peek-a-boo, the covering plays with the idea of presence and absence: "I can’t see you so you can’t see me“.

The paired animals in Rutting Creature 2 are draped in rich pleated cloths that evoke papal robes, a jester’s sceptre circled with large, chrome-plated bells protrudes from the crown of one of their enrobed heads. The uncovered legs and rumps of this rutting pair are sagging, grey and wrinkled. The term “mutton dressed as lamb“ comes to mind, that all this finery is merely covering up the futility of trying to cheat death.

At times, the sealed perfection of Robinson’s sculptures can be alienating to the viewer. But the very human flaws, the wrinkles and sagginess of the Rutting Creatures, do allow a point of entry. The symbolism is rich in these sculptures, although a sense of futility pervades both pairs. As with my initial reaction to Robinson’s work, fear can stop exploration. The sculptures suggest that an intense fear of death stops the fulfilment of life.

In the central room of the gallery is the enigmatic The Middle Place, a dwelling made of dyed felt capped with cedar shingles. The form suggests a warm safe place, but the chimney indicates that the dwelling may get too warm, a funeral oven. The door and chimney propose a possibility of escape. The house deep in the woods in fairy tales is a place of judgement, where the traveller needs to use their skills to choose life over death. The Middle Place seems to be a place of resurrection, where death is confronted and renewal can take place. It is here, then, that the real possibility of life lies.