An exhibition that has at its heart an exploration of flora is given a subversive twist in this re-configuration initially conceived for and shown at fortyfivedownstairs in Melbourne. Co-curators and exhibitors Andrew Nicholls and Clare MacFarlane asked a number of artists to consider the word “florid” and its older meaning “covered in flowers”.

Floral ground is well-harvested with exemplars from Margaret Preston to Tim Maguire by way of Georgia O’Keefe, all making intense contributions. It’s the Georgia O’Keefe immersion in the sexuality of flowers that is most relevant here. If “florid” can be a description of a kind of red-faced embarrassment or superabundance, then O’Keefe captured that ground with immersive thoroughness.

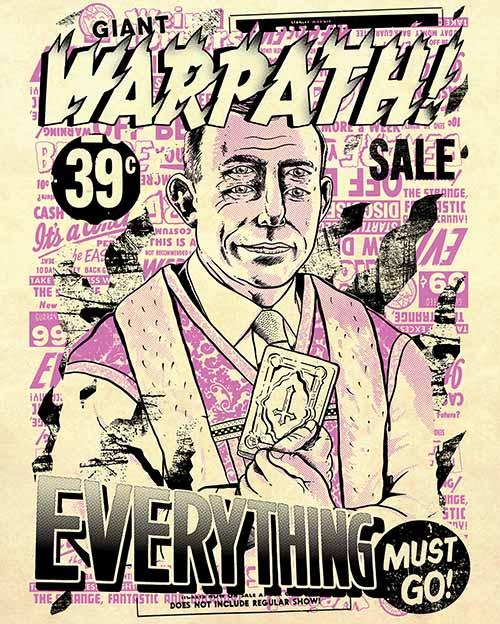

The artists share European heritages and, although scattered throughout a dispersed series of countries, a shared history infuses their approaches to the subject. A Victorian sensibility is present in the works, even through Ryan Nazzari’s red-faced cartoons hung salon style that draw a puzzled and confused series of characters through a world of multiple images and messages.

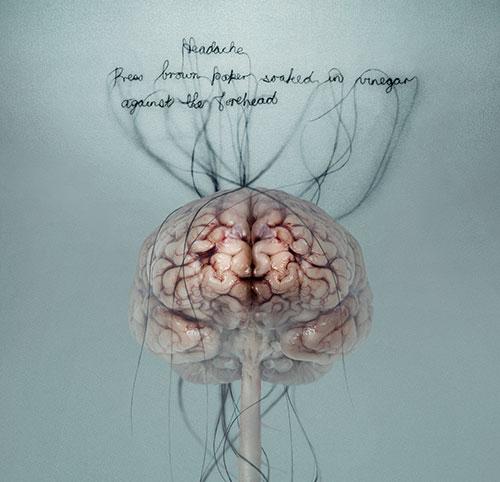

A further connective line is drawn from a fascination with flora, fauna and the human body, used as subject material for paint and stitch in domestic households. The plethora of doilies and painted studies that find their way into op shops in every corner of the country are a testament to the need to express a connection to the natural world, that could also read as a demented compulsion to keep one’s hands busy. The relationship between that furiously fascinated, documenting activity and the 21st-century obsession with recording the everyday banal or endlessly playing Candy Crush Saga asks exactly how much busy stuff we require to keep our minds calm.

Nazzari’s works connect in medium to Andrew Nicholls’ exquisite profusion of homoerotica, with mischievous figures disporting themselves among the flowers under a knowingly innocent gaze. The artist’s fascination with Gustav Doré, and references to etching techniques, tug on the threads of history. Sections of drawings re-fired onto found plates confirm the connections also found by Olga Cironis. Her use of found and re-imagined objects draw a clear line from earlier depictions of the natural world to a social/political use of text overlaying a stylised machine-made table runner tapestry. It’s the white in you that fascinates me is built upon in other works with the weaving of human hair mingling with hand-stitching. The works attract and repel in equal measure.

This idea of attraction/repulsion is also visited in Susan Flavell’s fearless ceramics. Her unconventional, seemingly clumsy forms with their crusted dry surfaces and ambiguous conglomerations of animal forms radiate with a nuclear salmon pink internal glaze. The objects are uncomfortable, awkward. Flavell forces us to ask ourselves on what basis we decide to avoid people and situations that are not acceptably beautiful. Clare MacFarlane continues the works for which she is well-known with paintings of sumptuous William Morris inspired wallpaper overlaid with the carcass of a honeyeater, accompanied by studies of the deceased bird while Mel Dare has produced a series of paintings through which she filters our understanding of flowers, represented by embroidery. These exquisite meditations of texture, pattern and form convey a floating harmony where the ‘stitches’ become their own self-contained universe of memory.

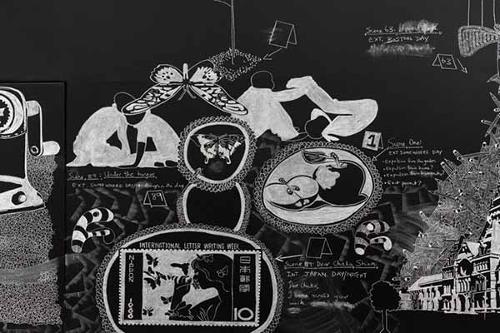

Grim memories of cold and dark dining rooms of great aunts are recalled by Eva Fernandez and Thea Constantino. Fernandez’ flora obscura documents WA native flowers as imagined through 19th-century photo technologies. The series intelligently locates these botanic gems within a circular format, and colours the backgrounds in mysteriously dark sepia tones. We lurch between the seductive beauty of the flower forms and the sense of wonder that earlier migrants must have experienced. Constantino’s series of portraits are dressed to impress. Starkly placed before a severe black ground, the masked figures are alternately passive, confronting or just plain terrifying. With their identities obscured, clues to their location and space diminish while time becomes irrelevant.

This exhibition draws us through a period of time and space, of early discoveries, of observation and the intense production of objects in the 19th and 20th-centuries. It also asks where we are now and what is important. Exhibitions of this calibre are essential as they set the timbre for where we are going.