.jpg)

The closest parallel I can find to this big picture history of Australia's art, is another “Big Picture” – Tom Roberts’ The Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. That commission had to include “correct representations of the Duke and Duchess of York, the Governor-General, the Governors of each of the States, the members of both Federal Houses of Parliament, and distinguished guests to the number of not less than 250.” It was an impossible task that produced a problematic painting that remains an important curio of Australia’s art history.

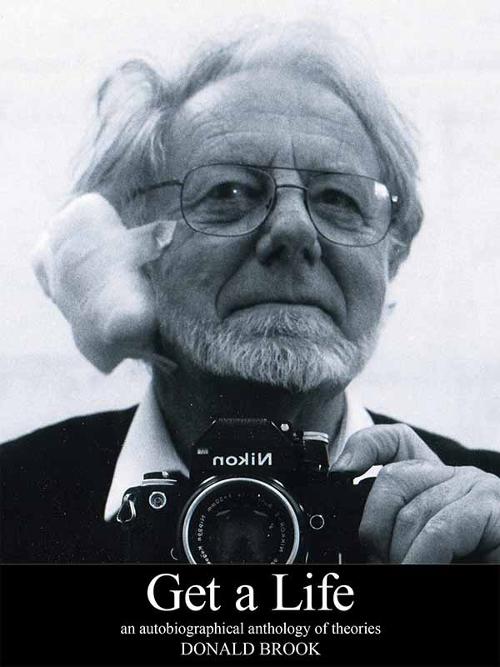

Sasha Grishin’s magnum opus has many more than 250 artists, as well as referring to (in comprehensive footnotes) significant scholarship in the field of Australian art. It charts developments from ancient cave paintings to the most recent multimedia constructs. However just as Roberts’ “Big Picture” fails to convey either the excitement or the importance of the event he was commemorating, so Grishin’s book is less than successful in showing the patterns and rhythms of our visual history. Nevertheless, it is a valuable contribution to the reshaping of Australia’s visual past and present and some of the framework for this mammoth structure provides new insights.

The author begins by acknowledging some of those who have made previous attempts. While this frees him from the cliché of following only in the footsteps of Bernard Smith, he does fall into the bad habit established by William Moore in his 1934 Story of Australian Art of adding long, sometimes meaningless, lists of various artists at different points. There is a strong suspicion that Grishin’s motives may be guided in part by self-preservation. With the best will in the world a single history can’t properly discuss every worthy artist. Excluded artists are often vocal and, on occasion, aggressive. By plonking many names in a long list, the author can claim they are in the book.

This practice has led to some contradictions. Hilda Rix Nicholas appears first on a long list of students who studied in Paris with little impact, but later she is an artist who received “considerable acclaim for her earlier work, both in Europe and Australia”. And, as part of a critique of the overly theoretical art establishment Fiona Hall is in a long list of neglected artists never considered for the Venice Biennale. Hall has been the subject of considerable acclaim from Grishin’s dreaded art establishment over many years, as is reflected in the detailed analysis here. In 2013 she was announced as Australia’s representative for the 2015 Venice Biennale.

Grishin’s other frame is to use much 19th-century art as a study of how Aboriginal people saw the Europeans and vice versa. This mixes with a straight historical narrative, illustrated by appropriate images, to make this section of the book a good introduction to colonial pasts. With the European hegemony of the late-19th century and beyond, this frame is discarded. I wish it had been resurrected in his examination of Australian art from the 1960s onwards.

The section of the book that deals with artists in living memory is the most problematic and it lacks cohesion. As the last decades of the 20th century coincide with the revival of Aboriginal culture it would have been good to read of the friendship between Wandjuk Marika and Tony Tuckson, as well as a proper account of the impact the young activists Brenda L. Croft and Djon Mundine had on the English internationalist Nick Waterlow, not to mention the way Brisbane’s Campfire Group captured the Queensland Art Gallery.

Both Grishin’s inclusions and omissions are a reminder that we are all creatures of circumstance. A writer more familiar with Sydney modernism would have known that one of the reasons for the surge of women artists in the early 20th century was the very supportive Julian Ashton who gave talented women students both opportunities and employment. Sadly the only reference to Ashton’s attitude is when he is described as “generally hostile to women artists”, the opposite of the truth. Someone less self-confident in his knowledge of printmaking could have looked more closely at A.B. Webb and those other remarkable West Australians of the early-20th century. A writer more familiar with the broad sweep of Australian visual culture would have included something on the impact of the Queensland Art Gallery’s groundbreaking Asia-Pacific Triennials which led this unfashionable country to be ahead of the vanguard in making Asian connections.

Although this is a valuable addition to our art historiography, anyone trying to grasp an overview of our art would be better off going to the National Library’s Trove where they can download a free copy of Andrew Sayers’ Australian Art (Oxford University Press, 2000) which lacks the detail of “The Big Picture”, but is a great impression.