Beautiful Vermin came out of discussions between artist Indra Geidans and curator Thelma John. Here a contrasting group of artists have been brought together around the difficult issue of the ambivalent relationship between humans and those animals classified as outsiders. The exhibition sought to reframe vermin through the lens of a positive visual encounter.

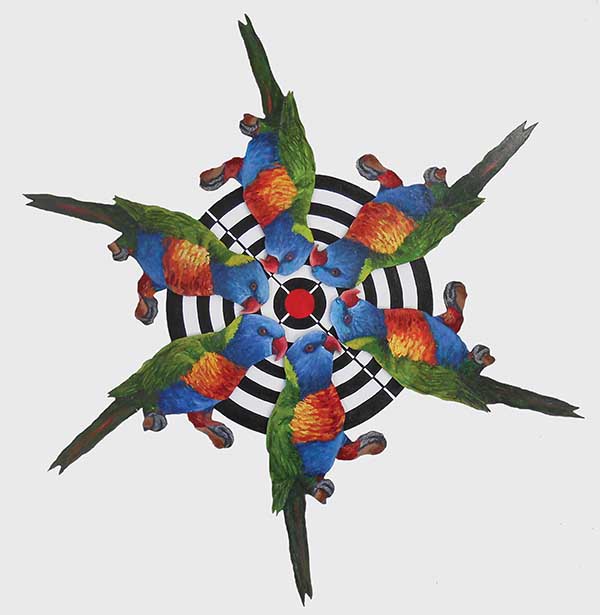

Geidans addresses the ambivalence of beauty and cruelty directly in a set of oil/acrylic paintings on shaped forms. Naturalistic rainbow lorikeets, foxes and other species form symmetrical arrangements around targets and target-like forms in the Vermin Mandala series. Vermin are there to be killed or eliminated, but what if you feel you cannot take part in this? Is it possible to retrieve the fox from its PR disaster? Debbie Walker Tremlett paints a vibrant fox in the small and intense oil on canvas Red Hunter. It is a haunting use of beauty to challenge our assumptions. Rona Green's five portrait prints of rabbits have also moved a long way from the experience of the animal itself.

Others in the exhibition take the perspective that humans are the ultimate vermin. In a complex work, Olga Cironis presents us with a roll/cloak of woven human hair on a metal stand in front of a large portrait of the artist wrapped in the coarsely woven cloak. Entitled After the last pearl is taken, the pearls of the title are scattered on the floor below the portrait to be accidentally dispersed around the gallery. The viewer must rely upon readings of pearls as representing purity and innocence or wisdom and female sexuality. So to cast these pearls before an audience could be interpreted as alluding to what is not valued and what audiences or the public may even seek to denigrate and destroy. The figure of the 'mother’ in her umber bridal gown of hair is one of the more untamed images in the exhibition.

Nearby, one of the pearls had come to rest at the feet of the pack of dogs/pups from the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. Whilst these grass and bound forms have appeared in many exhibitions, what is striking here is that they make us think again about the significance of dogs and dingoes in Indigenous Australia and especially the way the categories of wild and domestic are blurred in the figure of the dingo. The sculptures combine wild-harvested grass with bright acrylic yarns and raffia. Here the categories of what is natural and what is synthetic are not conventionally drawn. This syncretic reality is also featured in the works of Iwana Antjakitja Ken, Chayni Henry’s Hobby Farm and Frank Gohier’s Feral.

Yvette Watt is well known for works that directly reference the rights of animals. But The luck of the draw takes a different tack. It is comprised of a grid of cards mounted on the wall behind a table where two audience members can sit. The cards are small watercolours of animals (including vermin), human technologies and simplified maps as well as bold titles of human occupations. Many of the images are reminiscent of children’s illustrated encyclopaedia and seem to be hinting at colonial readings. The instructions at the table are for audiences to invent their own rules, the implication being that the orthodox rules of what is and isn’t vermin are culture-given or potentially that the position of feral animals and their effects are either unsolvable or up for grabs.

I credit the organisers for delving into the ambiguities of nonhuman relationships – and for asking us to examine our fears and to love what is declared unloved. The exhibition raises troubling issues about exactly where the agency of animals sits in the artworks. Is pointing out the aesthetic and moral ambiguities of our relationships, enough? Of course it is better to have an "art that invites us to engage and remember, rather than possess and to forget" in the words of Charlotte Du Cann of The Dark Mountain Project (see her blog) but the dangers with work that try to redress the Other through positive aesthetics, is that the violence of relationships may be erased or that lesser works fail to reposition nonhuman lives as having active agency: the animal’s point of view is lost. One work in the exhibition that was more visceral and risky was Emily Valentine Bullock’s Mynah Squadron. She has used feathers from Mynah birds she has legally trapped and combined them with aeroplane models to create a menacing flock – half animal and half not.