In 1968 the newly refurbished National Gallery of Victoria opened its temporary art gallery with seventy-four paintings and sculptures by forty Australian artists. This controversial inaugural show, titled The Field, displayed works which explored geometric abstract styles such as "Hard edge", “Colour field” and “Conceptual abstraction”. Its purpose: to unequivocally prove that Australian art could hold its own within the rest of the Modern Art world. Nevertheless, only three of the artists showcased were women.

With the opening of the new Hold Artspace in Brisbane's West End, young directors Luke Kidd and Kylie Spear also have something to prove. Their first show, simply titled Field, explores issues surrounding female artists within the contemporary landscape genre. Field utilises the work of seven young multi-disciplinary artists to interrogate the question of whether gender can directly influence the way an artist engages with their environment.

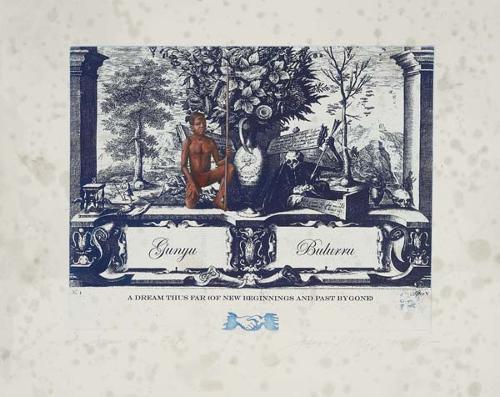

It seemed more than a coincidence that so many of the works in the space had some inclusion of the female body. The exceedingly precise and overly simplified manner of abstraction that occurred in The Field left the public grasping for something relatable to cling to; but many of the artists in Field have instead depicted the figure interacting with a landscape, either internal or external, to illustrate these interactions in a much more significant manner.

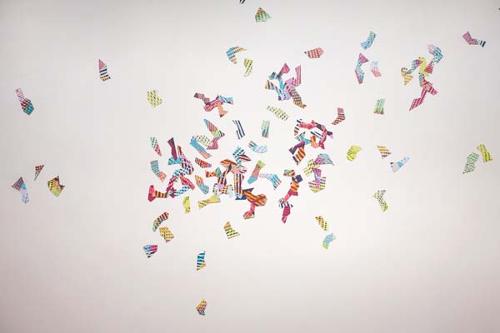

It is interesting to note though, that almost every figure depicted in Field has been, in some manner, manipulated or abstracted. Both series exhibited by Madeleine Keinonen feature bodies that have been obscured in different ways, even to the point where one cannot tell whether the subject is male or female. Her photographic series titled Exuvium (2012) examines the construction of the domestic identity through the depiction of familiar household floral fabrics wrapped around human forms, obstructing our perception of the individual underneath. In There’s No One Else Like You (I’m Just Like All the Rest) (2012) Keinonen disfigures the form through kaleidoscopic papercuts.

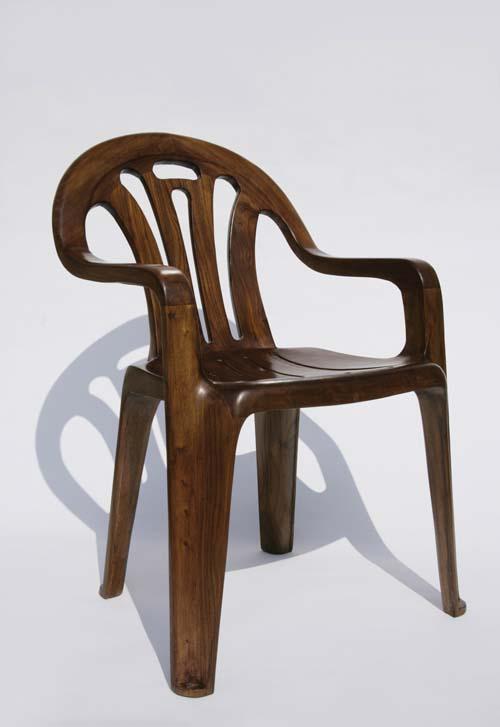

Camille Serisier’s work A Perfect Day (2012) shows an artificially constructed fantasy environment with the interaction of real life performers; again sometimes hidden, abstracted or wrapped in the surroundings. The series was first visualised in a collection of surreal watercolour landscapes. What then emerged was a photographic series of large scale paper sets: full of Australiana, pop culture references, and mythological symbols. The imagery in Serisier’s artwork is so full of allegory and symbolism that they beg to be scrutinised up close and deciphered.

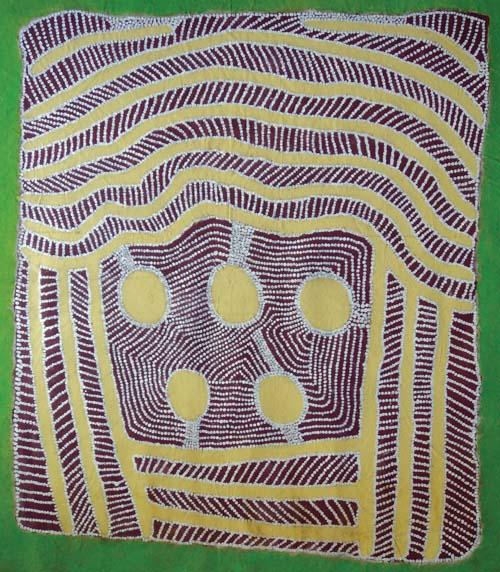

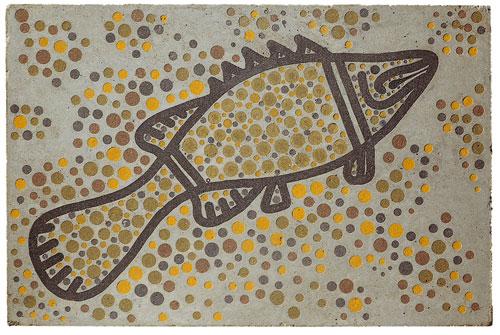

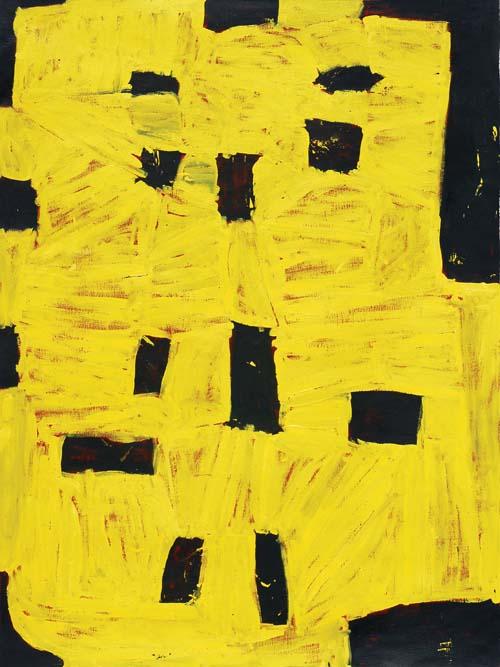

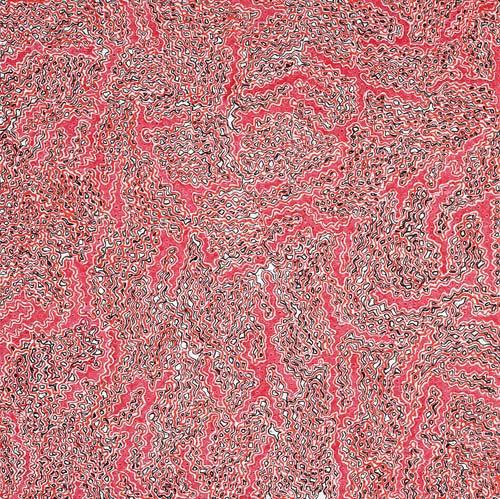

This is not to say that every work in Field was figurative; pattern and abstraction also featured heavily. The first that comes to mind is the geometrically abstracted works of Freda Davies, who rather than presenting an environment through a representational approach, wishes to intuitively portray the sentiment and atmosphere of a particular site. However, as opposed to The Field in 1968, in this exhibition large areas of flat colour and hard lines were nowhere to be seen. These works are small in size, and exhibit painstakingly detailed brushwork and texture within the simple arches and triangles that reoccur throughout the series.

Curator Lisa Bryan-Brown points out that basing a whole exhibition around questions of gender can be challenging - “laced as it is with equal parts negative sexist essentialism and positive feminist activism”. She also recognizes the great reluctance of female artists to be defined by their gender, for despite the fact that this show does not specifically label itself a “feminist” show; it cannot escape being laden with social politics.

It was pleasing then that the participants in this show did not make an obvious attempt to challenge or “out-do” the existing genre structures. Issues central to the show were tackled with sensitivity, thoughtfulness and honesty. Many of the works seemed understated, or even playful and humorous; but when considered further, became deeply profound. In fact, what many visitors found especially striking was the complete harmony of the artworks that comprised Field. All the works were carefully placed, with some of the individual pieces from the same artists’ series laced throughout the exhibition hang, so that the relationships between artworks became even more apparent. Every work suggested dialogues running between them. There was also absolutely no sign of artistic territorialism in the space; which seems absolutely appropriate when contemporary feminism has become so much about inclusivity. Constructed entirely by young artists, directors and curators, this exhibition shows the individuals involved to be exhibiting a professionalism that can be judged as beyond their years. Instead of proving artistic worth through grandeur and confrontation as in the 1968 exhibition, this exhibition evokes an inherent sophistication and complexity undeniably as powerful as it is subtle.