Two installations, each a viewing platform onto complex territories of history and poetry, comprise WA artist Kate McMillan's new exhibition In The Shadow of the Past, this World Knots Tight. As a new chapter in an artistic engagement spanning more than ten years and involving installation, photography and video, these works are a concise demonstration of McMillan’s control over the potency of the objects she presents.

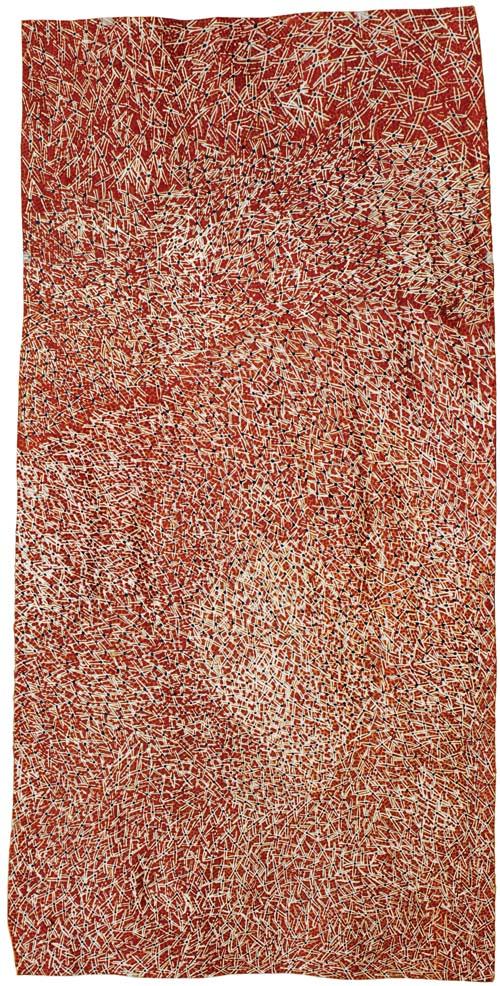

The first work in this duet is The darkness saunters, and then sits with me, an ensemble of objects recreating a domestic space. Two painted canvasses flank a leather armchair in good resemblance to a modern sitting room. The paintings (on first consideration) are innocent abstract shapes made of poured black paint, the chair is fashionable, circa 1970s, and looks comfortable. The palette of this setting conjures up décor verbiage: taupe, mushroom, faun, greige.

This is not a chair for relaxing in, however. It offers something very active: a kind of astral travel. In Ming Dynasty China, city-dwelling landscape poets found acclaim by writing lengthy descriptions of their longing, or pi, for natural forms like waterfalls, mountains and forests. Despite being nowhere near wilderness, they’d dream up natural imagery through meditation, sitting indoors and gazing at rocks specially selected for their ruggedness. McMillan invites her viewers to partake of this armchair travel, or woyou, from the comfort of her constructed interior.

With this in mind, her canvas paintings become activated as devices of free-association. The black blots, like Rorschach prints, ask us "what can you see? what are you capable of imagining?". Yet, it is difficult to be confident of any meaning brought on by the glut of paint upon the canvas. The blots are silent and unclear, obliging us to proffer any image we can, be it landscape, dream or dim recollection, influencing the work’s meaning more strongly than in artworks where we can guess the artist’s intentions.

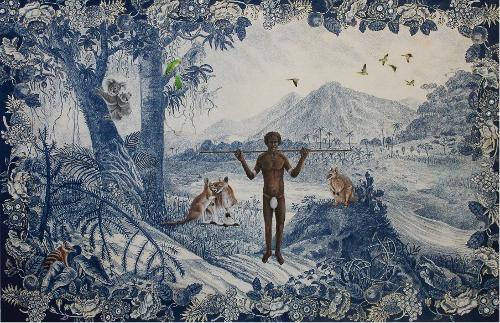

In the shadow of the past, this world knots tight is an artwork that describes other places through memento. The installation contains two torn photographs, framed and hung upon a neat stripe of matte house paint. The photographs show a craggy precipice on Mt Pilatus in Switzerland (a peak strewn with gun emplacements, toboggan tracks and once thought to house a terrible dragon). The outcrop is veiled with thick white fog and only visible in the foreground - a viewpoint with no view.

On a shelf below the pictures rests a characterless lump of cast bronze, resembling a film prop or something you might collect twelve of with a magazine subscription. It’s an imprint of the silt bed at the bottom of Governers Lake on Wadjemup, or Rottnest Island. A quaint tourist destination off Perth, Rottnest keeps a quiet history of military fortification, shady colonial indigenous penalisation and influenza. This shiny little portrait of the island is indistinguishable as a local recording. Neither object offers us a good account of Wadjemup or Pilatus, yet they are intrinsically linked to those places as secondary echoes of the landscape.

It is the ambiguity of silt, the fog and McMillan’s paintings that form the crucial link between these objects. In focusing on the gloomiest parts of the landscape, McMillan shows us how cursory and unreliable are our efforts to make impressions recall a place. Be it a holiday snap or a geological sample, the mementos we take from the landscape tend to lose value when they are removed from their context. Perhaps this is how McMillan regards history – as an incomplete story whose gaps are filled by assertion, half-memory and wishful thinking.

Despite the diminutive setting of Venn’s Gallery 2, McMillan’s modest exhibition is complete and her ruminations on free association and landscape are cohesive, perhaps more so than a larger exhibition might be. Indeed, as a kind of '”exhibition EP”, the work is able to provide a punchy interim account of McMillan’s practice.

There is always a lot to unpack from Kate McMillan’s work, and it is difficult to delimit the connotative power of these two complex multimedia installations. McMillan is an artist who deals in un-memory and decontextualisation as subjects, rather than approaches, and as a result provokes reactions as intense as they are various in her viewers. Perhaps the trick in considering it lies in recognising when to stop thinking and just enjoy the beauty of the work.