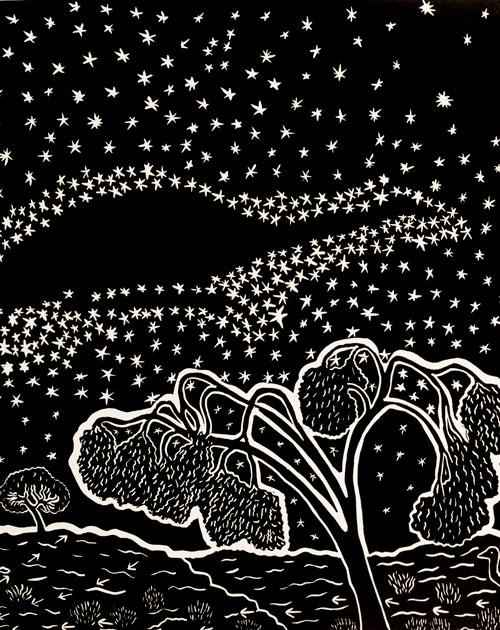

We often think nature is more real than thought. Philosopher Jane Bennett describes earthiness as being alert to the experience of sensuous specificity. Artist Savanhdary Vongpoothorn's work might fit into such a definition of earthiness because her new perforated paintings are real and sensory evocations of the scribbly gum tree.

Words like "nature" and “earthiness” have previously been understood as phenomena that existed anterior and posterior to terrestrial life. In other words, infinite. However, in recent times, perceptions of the earth bring associations of fear, as our wildernesses shrink and extinction looms. These are troubled environmental times, and the anxiety of precipitating natural disasters have infiltrated all areas of thought, including philosophy and art.

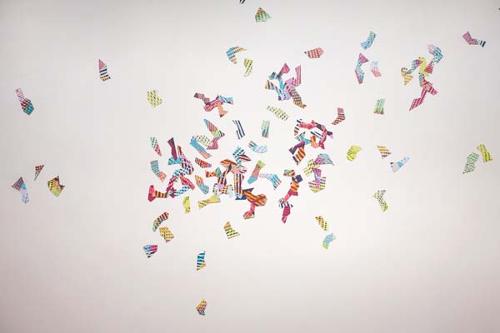

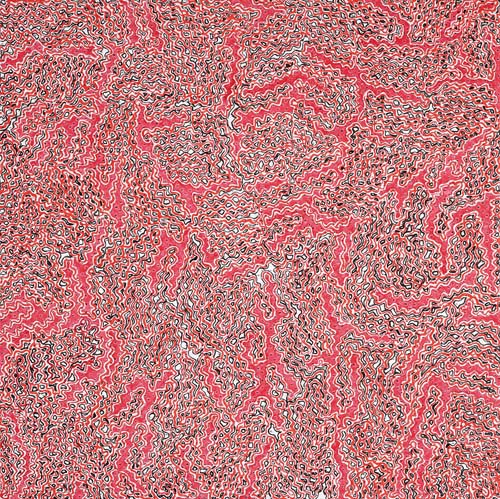

The patination of scribbly bark trees, as Vongpoothorn suggests in her title, is an exploration of the beautiful as force. Her paintings duck and weave, a labyrinth of squiggly lines and camouflage bark patterns. In these abstracted investigations of tree surface, the colours of the trunks beggar belief, exploding into violent purples and reality-resistant pinks. Her paintings are as fluid and multi-lined as a contour map. Leon Trainor says, in his catalogue poem, that spirituality: “dwells, too, in the moth-messages that migrate to your stretched, perforated cloth”.

As well as a force of spirit, the artist’s scribbly gums can be seen as a force for change. History has shown us that force is a useful tool for shifting perceptions, in a deterministic sense. Perhaps Vongpoothorn’s interest in the beautiful creates a curiosity about forces for change. Change can be frightening and these works convey a degree of fear and trepidation. This interpretation, born from empathy rather than dispassion, is based on the emotive nature of the artist’s hand gestures, there on the canvas. The marks appear as worry lines or erratic life-lines, rather than scribbly lines. These are marks made from a tremor, or was the tremor caused by the marks, resulting in a quivering twitch.

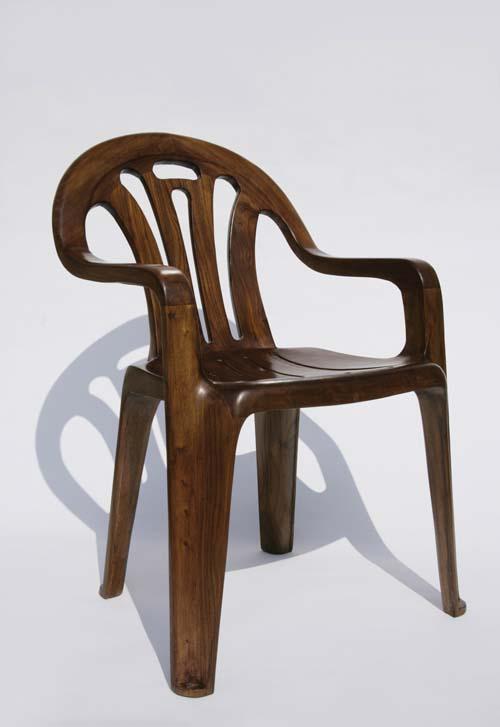

In a related examination of force, it was not an arbitrary decision to begin this review by introducing Jane Bennett, a John Hopkins University philosopher of vitalism, agency and spiritual force. In fact, Vongpoothorn’s catalogue introduction mentions all three of these criteria. However the big question might be whether these vitalist principles function as judgements for aesthetics, as the title implies: have anima and autonomy replaced beauty in the competition for audience attention? I would argue that when they are co-dependent, they are most effective.

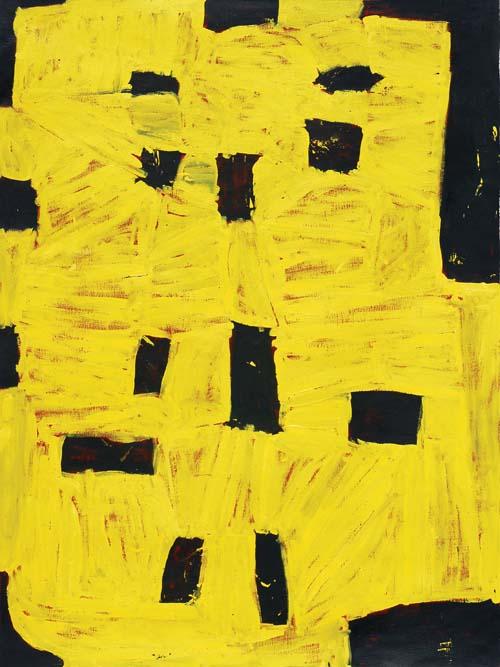

Vongpoothorn’s paintings have always yielded visual pleasure. She has done this through conventional abstraction tactics, such as surface quality, reductionism, familiar form and a quest for essence. Essence is the difference between the painting’s qualities and our perception of those qualities. This means the object or painting pulsates, has rhythms and affects other beings, in equal measures to the effects we believe we have on one another.

These new paintings, based on the military-style concealments of the bark of the scribbly gum tree, have this essence. They have an ability to connect a viewer, apart from and in collaboration with the material qualities of surface, support and structure. They do reverberate and shimmer. However, the emotion that fuels and mobilises this essence has shifted towards that of fearful unease.

The concept of beauty has shifted too, in a context of aesthetic criteria. Conventionally a formula for discerning taste and artistic success, beauty now brings with it an air of longing and memory. We have trouble recognising it. This is a shift away from subjective ideas of beauty and a move towards the exchanges of emotion, as a form of beauty.

With a final note on essence, that schism between the painting and its qualities, it is when beauty and essence become entangled that we are truly engaged by an artwork. For this to occur, beauty has to be slightly beyond our knowledge. In other words, essence is the unknown spaces between what is familiar and unfamiliar. If beauty is bound by what we know too well, it becomes mundane. In this case, perhaps the scribbly gums are familiar but also concealed and, so, we are bound by their earthiness and hyperreality.