Back in deep time a man worked on a stone, hitting it with another to break off sharp-edged flakes for use as scraping tools. He left behind the core and it speaks to us now, unearthed in 2008, on the banks of Parnkupirti Creek, a tributary of Paruku (Lake Gregory) in northern Western Australia. The latest dating technology puts the flaked core at 45,000 to 50,000 years old, a new benchmark in the occupational history of northern Australia. This was a major archaeological find but unsurprising for the Walmajarri people of the lake, who knew that their ancestors had always been there, since the Waljirri - the "Dreaming" or creation period.

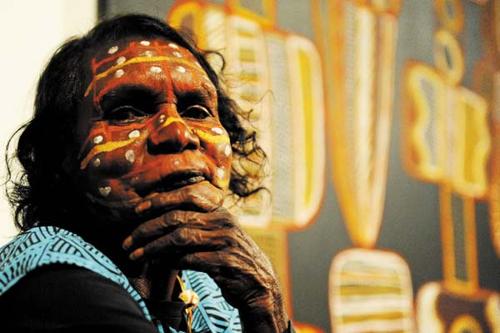

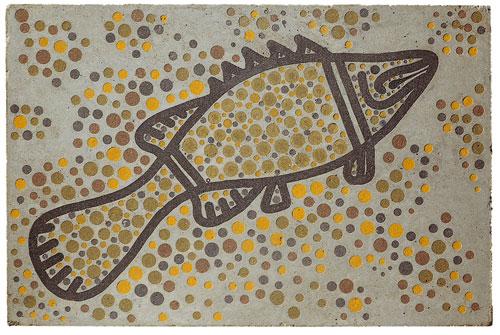

The excavation resulted from work at Paruku over decades by geologist Jim Bowler, one of the co-discoverers of the Lake Mungo sites in NSW. Hanson Pye, senior custodian, responded to the find with the painting Parnkupirti Layers (2011), a succinct conceptualisation of Walmajarri history and worldview. Stylised geometric motifs, adapted from the work of his grandfather, well-known painter Boxer Milner, 'occupy' the whole work, unifying the time of his ancestors – the dark lower layer as revealed at the excavation site – and the present, the light upper layer of “the whole area where we’re living now”. The two are inseparable, “the same”.

This painting is like a standard bearer for the exhibition Desert Lake. Though small and visually muted, it speaks directly to the intentions and experience of the ambitious project that gave rise to the show, in which Walmajarri and kartiya (white people) have been seeking out meeting points between their different ways of knowing the land. Parnkupirti Layers was made out of one such meeting point. The mapping undertaken by kartiya artist and writer Kim Mahood and some of the senior Walmajarri women was made out of another.

The on-going project has its roots in long-standing relationships, such as those of Bowler and Mahood with the Walmajarri. The creation of an Indigenous Protected Area over the lake region in 2001 drew other outsiders into ongoing work with the Walmajarri in community development and land management, as reflected in some of the “history paintings” in this exhibition. In 2010 a new articulation of aims and funding, driven in good part by well-known landscape painter Mandy Martin, led to periods of intense activity drawing in many more visitors and resulting in not only this exhibition but a book.

Mahood, who grew up on a cattle station to the east where many forebears of present-day Walmajarri were employed, was invited in 2004 to help set up a women’s centre at Mulan, the closest community to Paruku. The first mapping exercise grew out of the women’s travels with Bowler around the lake in 2005.

“We needed a means of recording both kinds of knowledge that didn’t compromise either. The template of a painted topographic map provided common ground and could be read easily by both Aboriginal people and kartiya,” writes Mahood.

Two maps are on show, visually alluring documents of the process. One charts family jurisdictions at Lake Stretch (part of the Paruku system), a reminder of how complex collective decision-making is in the traditional context. Another uses colour-coded dotting to create a six-year fire map across the entire Paruku Indigenous Protected Area, which points to the possibility of some areas being burned too frequently. The map provided a useful tool to have this land management conversation, but it was clear, writes Mahood, “that the people who painted the maps invested them with meanings outside my understanding”. It is also clear that the mapping’s visual language has structured a number of paintings in the show.

Among them is a striking collaborative work, titled Fire Ghost (2012), by Mahood and Veronica Lulu, the most successful of the Mulan-based painters. Again a small work, it nonetheless conjures the vast sweep of the landscape, the ghost of the fire spreading across it as floodwaters would in another season, veiled by the green mist of new plant life and the radiant heat of a desert summer.

Alongside these relatively humble but highly communicative works, the series of large five-panelled landscapes by Martin seem to sit apart. They are impressive for their evocation of the “materiality” of the place, including the “elliptical skies with burnt-out centres”, as she writes, but they pull in the direction of a ‘high art’ show while little else does. The project afforded her a stimulating opportunity and precious permission, and certainly her history painting workshop was productive for the Mulan artists, yielding interesting paintings such as Shirley Yoomarie’s Working with scientists (2011). However the project’s broader undertakings do not seem to have been central in Martin’s own work.

Her key interlocutor, as attested in her artist’s “diary” in the book and as is evident in the work exhibited, was fellow kartiya artist David Leece. She writes of common strategies of size, format and palette that they both adopted for their work on site. She writes too of arriving at Paruku with her mind full of shoreline imagery from David Malouf’s writings as well as a developing interest in neurophysiology. She referred particularly to the latter when I asked her about the ways that the project had affected her work.

On site, often working alongside Leece, she made studies, “simple visual representations”, modifying her usual approach in part out of a “sense of humility” at working in Aboriginal country. However, in the studio she says she introduced other references and layers of meaning, developing her response to the “atmospherics”. If the works can be seen as even “cognisant of the view of the Walmajarri”, as she intended, then that seems to have happened incidentally, with the Walmajarri expressing their “opinion and keen interest” and Hanson Pye ultimately giving her five works the name of Falling Star, the creation story for the lake.

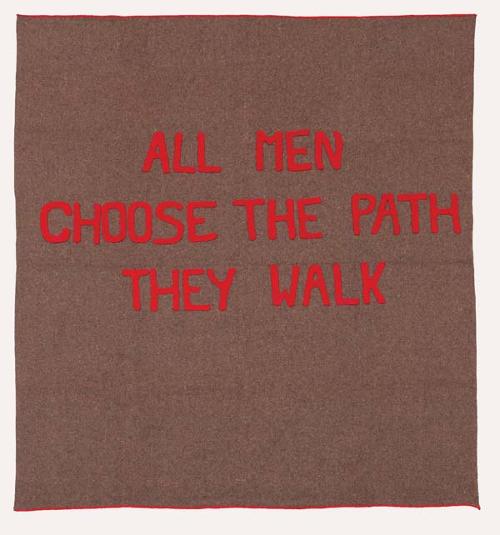

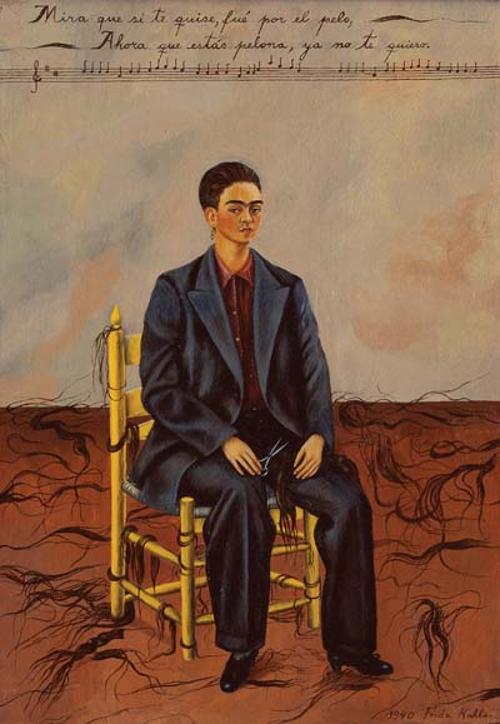

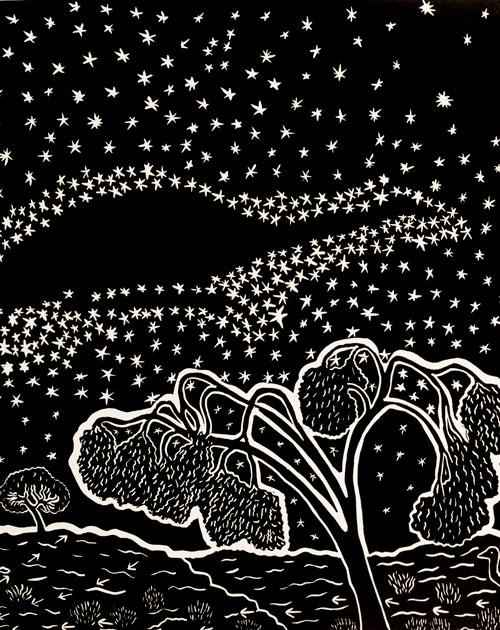

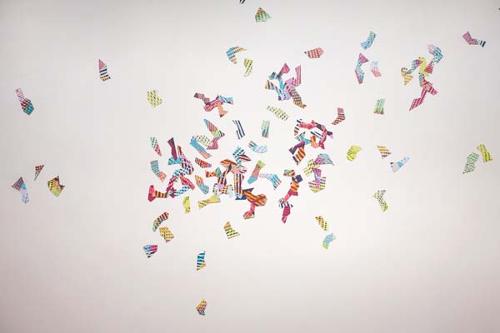

The aesthetically pleasing ‘collaborative’ screenprints, in a folio published by Martin and printed by Basil Hall Editions, are also not quite what they seem. They layer into a single work the imagery or text of more than one artist, Walmajarri and kartiya. For example, journal notes of anthropologist John Carty lie beneath a print of Pye’s Parnkupirti layers; a drawing of a tree by Leece is superimposed on an image of the lake by Daisy Kungah and a written song-like testimony by Chamia Samuels. However, as Martin reveals in the book, the final act of composing these images, using the acetates by individual artists, was hers. ‘Composite’ would seem to be the more appropriate descriptor. Even so these images suggest interesting possibilities just as the exhibition as a whole does – the generative possibilities of cross-cultural meetings of minds in an exceptional part of the world.