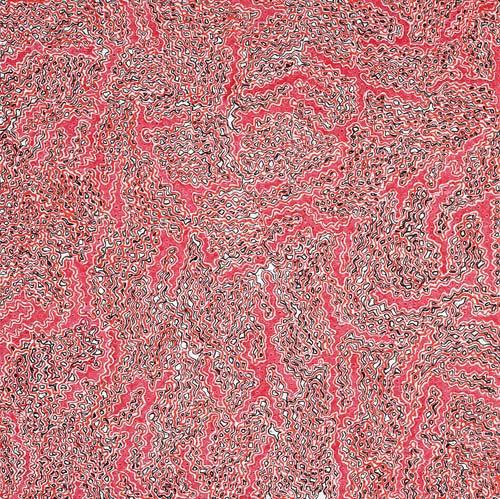

Aboriginal art is a new genre in art (and perhaps the oldest). A genre is a category that identifies a type or form of culture as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions. Aboriginal art is contemporary and traditional, it is anything an Aboriginal person says it is.

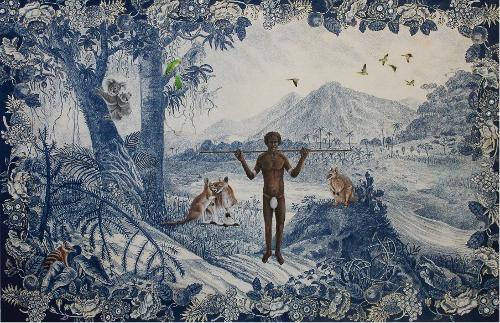

What makes Aboriginal art a genre is its link to a certain nationality or ethnicity, a certain historical position and experience. It connects incredibly disparate artworks. Provenance is very important in art, a casual scribble can be very valuable in financial terms if it was made by a famous artist. The provenance of Aboriginal art links it to 'authenticity' and to ‘truth’. A hangover from ‘the noble savage’ and ‘primitive art’ it has its uses but has tended to segregate Aboriginal art as a protected species, a special case, a sheltered workshop. Breaking through this status is an ongoing project.

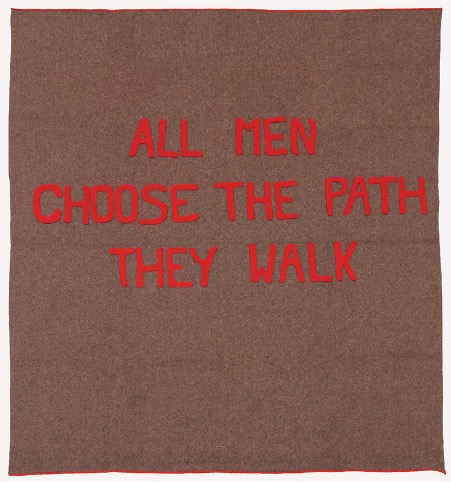

A lot of Aboriginal art is about history and the injustices of history. About lost stories, buried stories, ordinary stories, amazing stories, old and new stories, stories of tucker, creation, survival, politics, family, humour, darkness and light. About re-viewing, re-visioning the past and the present to show them from different angles, different perspectives.

It is the struggle for and the lack of justice that often makes art happen not its presence. Who makes art about justice? Well, maybe there is such a thing, maybe the idea of balance, of a rapprochement between the order and the chaos of life is art about justice or at least approaching some kind of wisdom.

Speaking of wisdom - in the obituaries presented in this issue of Artlink Indigenous we learn more about the powerful histories of some very significant artists whose artworks draw together all kinds of important stories. I get goosebumps when I read these obituaries and know that the examples these people set are about emotional intelligence as well as about art and life. No separation.

...

In the last Artlink Indigenous we promised to look at the criticism of Aboriginal art. It’s a rich topic and a controversial one.

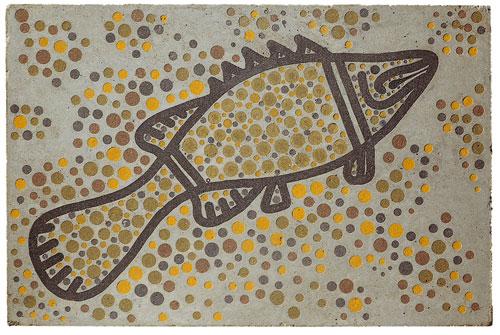

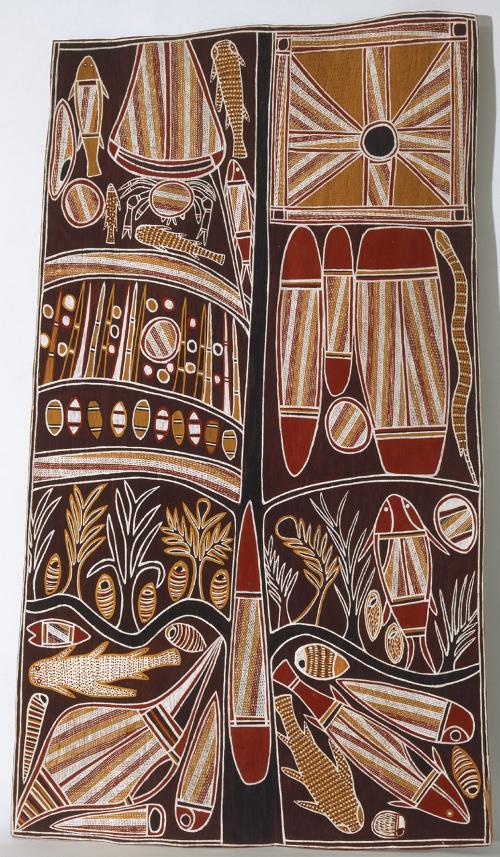

Australia is swamped with Aboriginal art pouring over the country, washing up everywhere in galleries, auctions, shops, a tide of productivity, innovation, lack of innovation, experimentation, lack of experimentation – a hungry mountain of paint, canvas, fibre, bark, paper, clay, ink, wood and everything else. It can feel overwhelming. Once somewhat of a novelty it is now an epidemic. There is no question that some of it is very good and some of it is mediocre. There is no question that Aboriginal artists get opportunities in Australia and in other countries based on their ethnicity as well as on their talent. But is it safe to say so? Will you be called a racist if you do? Can Aboriginal art be judged, criticised, evaluated? Can it benefit from critique? Or is it beyond critique because of its origins? Does the high moral ground of history segregate it and make it unassailable? Then again is any art in Australia really criticised?

…

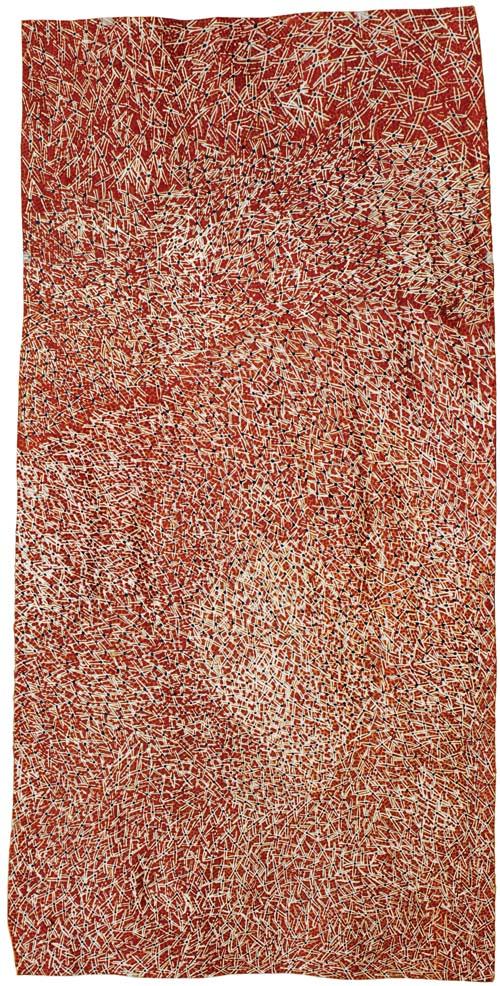

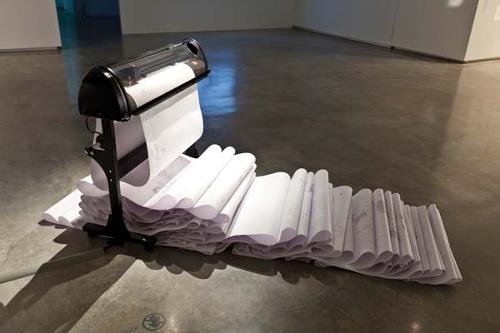

Award-winning filmmaker Warwick Thornton’s video installation Mother Courage, first shown at the cutting edge mega art exhibition dOCUMENTA(13) in Kassel in 2012 and now parked outside ACMI in Melbourne until June 2013, consists of a typical Central Australian Toyota van within which a projection of an Aboriginal grandmother rather mechanically painting a loose canvas with dots is accompanied by her bored grandson who is listening to the radio, an excerpt from Thornton’s 2005 film Green Bush which was about a bush radio station, playing songs to "those of our mob who are ‘a captive audience’" i.e. in prison.

In an interview Thornton did on ABC radio in February this year with Daniel Browning, he describes how he wants to make art that makes people work, that makes them get off their chairs and find out more on a journey of discovery. After seeing this work he thinks they might go and find out more about Aboriginal music, about Aboriginal radio, about the Intervention, about Aboriginal painting and about the courage of women.

In Kassel last September I encountered the travelling van of Mother Courage parked outside the Brothers Grimm Museum. Thornton’s van was like a slice of life lifted from Central Australia. On the inside was the projection and its sound filling the space, on the outside of the van rough paintings hung, in the front of the van familiar-looking old biscuit tins held travelling necessities. These small details brought home some things I know, the importance of a sense of location, the vast territories stretching behind the intersections of global and local meanings.

…

In the meantime a quiet revolution in Australian culture began on 12 December 2012 at 12pm. That was when NITV National Indigenous Television began broadcasting as part of the SBS family of free-to-air channels. Since July 2007 the station had been broadcasting on a limited basis while training and building expertise.

NITV’s aims are clear. “NITV tells stories and showcases the rich diversity of culture, languages and creative talent from all over Australia. It sends out positive messages about Indigenous Australia and speaks primarily to Indigenous Australians. We are the only channel in Australia that is 100% dedicated to reflecting the culture of Indigenous people.”

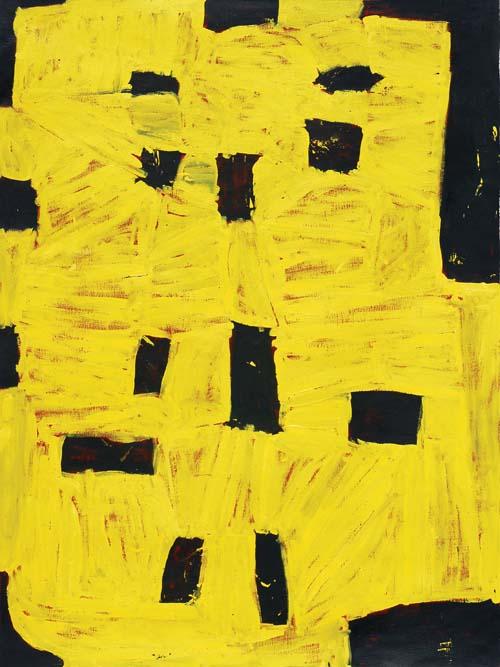

Premiering on April 28 2013 is Colour Theory with, as its presenter, art provocateur Richard Bell who describes himself as “an activist masquerading as an artist”. It was at the 2011 Cairns Indigenous Art Fair that I heard Bell say that being a black man in New York did not seem to put him at a disadvantage – rather he noticed that it was being a woman that meant being discriminated against.

Like Aboriginal art, NITV is something to celebrate and will change Australia. When a news broadcaster talks about “our people” it makes you sit up. When you see different faces and voices on TV it makes you sit up. It expands normality, making all kinds of experience graspable and visible. When you hear different stories, see things from different angles and make connections it opens your culture up. Good medicine, and as Archie Roach said at his Into the Bloodstream concert at the 2013 Adelaide Festival: “Everybody has a story.”