Sacred song, keening, kids, dogs, tears, flies, heat, song, chips, coke and smokes filled the clinical space. Outside, the sleeping mats and mattresses of the vigilant encamped families crowded the grounds. I remember one miner's wife bringing a casserole and giving it to the first person she met. She had never met Gulumbu and didn’t know what was happening but after driving past for a week she knew that something important was happening and wanted to contribute.

Gulumbu and her sisters awoke every morning of their childhood the same way that Yolngu kids have always woken. Their father would rhetorically address the pre-dawn glow and pronounce the seasonal and ritual imperatives for the day whilst their mothers keened the sun up. This is customary Yolngu habit.

But Mission life and sleeping in bedrooms and houses broke that pattern. Her big sister Gaymala revived the milkarri (women’s sacred keening) to open the Gapan gallery at the 2002 Garma Festival. When Gaymala died in 2005 Gulumbu took up the leadership of this revival.

As she lay in a coma at Nhulunbuy Hospital surrounded by her keening sisters she stirred. And a niece placed a mobile phone recording of Gaymala crying on the pillow next to her head. Gulumbu joined her sister in keening milkarri although remaining unconscious. And, of course, this event was captured on a mobile too.

When people ask me the most cutting edge new media event of 2012 I don’t hesitate. A comatose person rode her last hours of existence out serenaded by a dead person in an artform that they each brought back from the dead. To me, an artist is an artist, even in a coma.

When the new extension opened at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala a strange apparition appeared on the floor. Four perfect Gulumbu stars. This was probably the result of some complicated refraction of sunlight through the spherical skylights. But everyone knew that she had not been stopped by mortality. That extension is now called the Djotarra Wing in her honour.

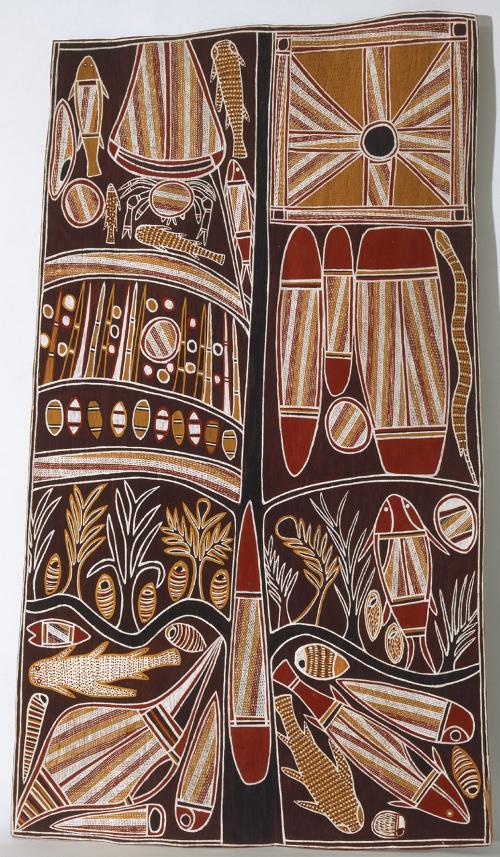

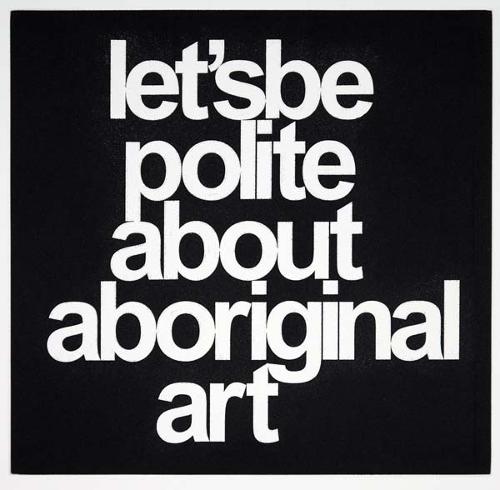

Yolngu art is sacred art. It intersects with the commodified world in the same way that artists and artisans of religious icons in old Europe had wealthy patrons who showed their piety by sponsoring beauty.

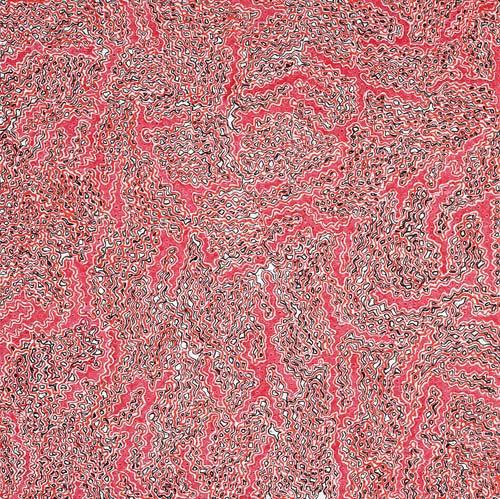

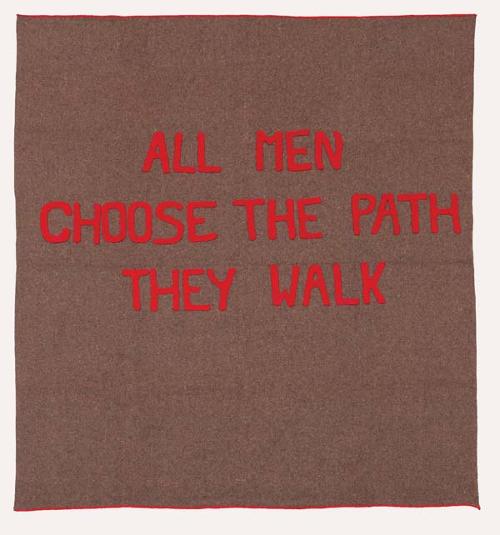

But the most successful Yirrkala artist of the last decade never painted her own Gumatj clan sacred design. It was this same holy lady, Gulumbu Yunupingu, who painted the infinite stars as a portrait of global humanity. It was a philosophical statement rather than a religious one.

Her father Munggurrawuy spanned First Contact, rebelled against the Mission, fought the miners, founded his own town at Gunyungara, trumped his ceremonial challengers and fathered two Australians of the Year. His humour and courage pulsed through the community for his whole adult life.

A scene of one of Ian Dunlop’s seminal 29 Yirrkala Film Project movies has Munggurrawuy negotiating with Narritjin Maymuru who wants to cut a canoe tree from his country. Narritjin was the Forrest Gump of Yirrkala, a participant or witness to every major event of the 20th century; a boatboy at Dhakiyarr’s surrender, strafed by Japanese when Reverend Kentish was captured and beheaded, suggesting the Yirrkala Church Panels and probably the Bark Petition, and leading the Homeland Movement.

The Seven Sisters or Djulpan constellation have their helical rise to coincide with the harvest season. They paddle across the sky pursued by three brothers with their bounty and sink below the horizon to the North where they cook. Gulumbu explained that the cloud form that echoes their cooking fire is, in some millennial events, actual not metaphorical. I finally understood that she was telling me that volcanic explosions in Indonesia or extended drought-formed dust storms in Irian Jaya can be seen from Australia. Not in our lifetime but within the life span of Yolngu knowledge. Whilst Southerners try to revision a history where China has always been our best friend, the Yolngu have been in visual contact with Asia! We were able to realise this gem of Australian knowledge in the Seven Sisters project when she led her sisters Barrupu, Nyapanyapa, Dhopiya, Djerrkngu, Djuwandayngu and Djakangu to make a constellation of seven individual massive prints and an eighth collaborative one.

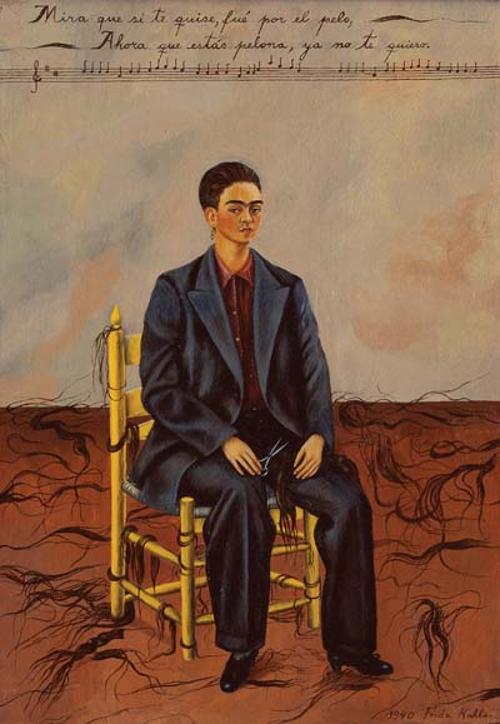

After two days of frenetic activity her sisters were deep into intricate and colourful multi-plate images and she was still scratching an awkward line drawing in one corner of the zinc plate. I timidly queried what she was thinking of doing and she pounced on me. "This is how we tell our stories. Not with decoration. Not in pretty pictures. Just like this!" I was mollified and it became my favourite of the series as it is indeed without anything but the lines necessary to the narrative. No gloss, no sugar. Her doctor explained later that she was probably struggling with the effects of a silent stroke. It was pretty characteristic of her to turn a disability into a virtue.

It was as a young woman that she began to translate the Bible into the Gumatj language over an eighteen year period with her great friend Mutilnga Ganambarr and two missionary teachers. When she won the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 2004 after a few short years of painting she thought it might not be deserved but a fair reward for a lifetime of unacknowledged labour as a translator for the Church.

Her Dilthan Yolngunha Healing centre was an expression of her compendious knowledge of natural healing. When her daughter Dhambit was run over and written off as a vegetable by the doctors she moved to Darwin and applied for a permit to harvest bush medicine. Every fortnight she and her wild-looking French son-in-law Tony wheeled Dhambit out to the dunes behind the beach, dug a hole and built a bush sauna with Pandanus nuts, reeds and medicinal plants, put her on the ashes and covered her with paperbark. She is now whole and painting. The only casualty of this process was when Tony was arrested carrying an axe across the hospital carpark. Even his closest friends would have to admit that he looks like an axe murderer, even without the axe.

Once I bragged that I had speared a mullet and she scoffed. “Have you ever got two with one shot? I have!” When her husband, Mutitjpuy - also a Telstra Award winner in 1990 – was dying, they moved to Birany Birany homeland. There was no one else there and he was frail so she had to hunt for both of them. Women do not spear fish, unless necessary.

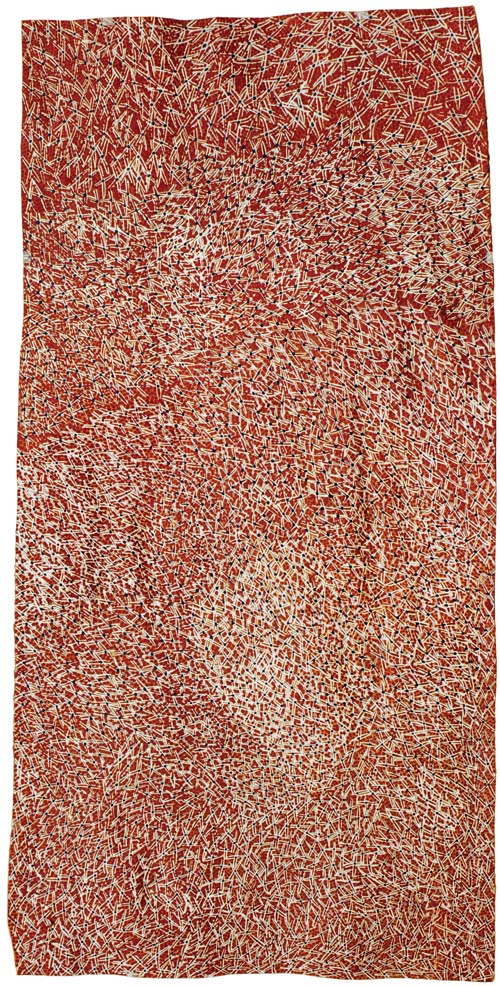

After she won the Telstra I followed her around as she spoke to the various journalists, writers and academics who wanted to discuss the stars. Gulumbu kept stressing that we look up to the stars, just as trees grow up, people sit or stand up. Like the rest of her audience I could not grasp what the significance of the word “up” was. But over time it started to dawn on me that she was talking about the direction of growth. And that stars can equate to spirits.

Yolngu who are not presently with a body exist within specific bodies of water in North East Arnhem Land. These beings can exist in the astral dimension as well as ethereally within the water on an earthly plane. An example is the Manggalili clan souls in the Milngiyawuy River, which flows into Blue Mud Bay which is also the Milky Way.

And so she was saying that the life force inevitably matures into non-corporeality as a natural stage of growth. The reason that the Westerners weren’t hearing her was that in our language she was saying: “When you grow up you are going to be dead”. In fact she was saying that what we call death, and think of as a full stop, is actually a growth stage. When I asked her if this was what she meant, she smiled.

She also said that the larger star shapes she represents are those visible to our naked eye but the dots, which fill the rest of the field, are those that we cannot see which are there as well. She said that if you could see everything that exists the night sky would be nothing but stars. I was shocked when I heard that this is also the Western scientific view.

It is traditional that all possessions of the deceased should be taboo and destroyed as the lingering spirit needs to be eschewed so that a clean break can be made for the departing spirit and a timely renewal of their cycle can occur. I handed a heavy calico bag to the ceremonial people to accompany her body at her Dhanaya homeland ceremony. It contained her rocks. Unlike every other Yolngu artist before her, Gulumbu collected pigment from everywhere she went – China, France, Sydney. For her, black was not just any black and red not just any red. She was a colourist of natural ochre. Her eye was always caught by the shade of a rock in a carpark or a suburban garden. She accepted all colours.

And in that strange week, in the white mining town, people of all colours gathered to cry for her.