.jpg)

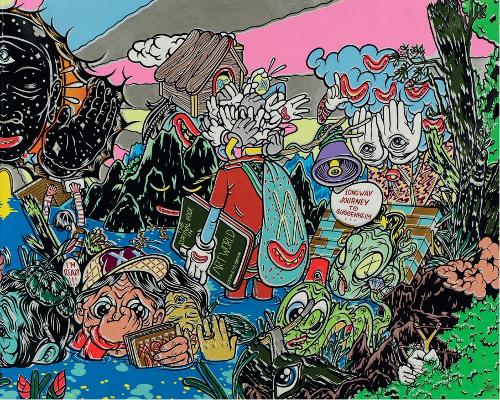

Peter Tyndall is an artist of radical first principles. His work, shown in a survey exhibition at Anna Schwartz Gallery, addresses the way our art perception constantly moves. Art's elements and capacities are unstable and, from the very beginning of his creative career in the 1970s, Tyndall has engaged with the emergent experience of art. His work disrupts habitual looking. Consequently, writing about his work is an equal exercise in disruption. So, the act of writing is also a return to basic principles; an attempt to remember what we do when we look at a work of art, a wish to shift away from reflective description, towards textual production. Carpentry of things is the key.

What do his paintings do? What things are these we see? Our critical and technical vocabulary feels inadequate. Can we respond without critique or judgement? If I feel a shock of electricity when faced with an exhibition of Tyndall’s paintings, can I articulate why? Perhaps it is enough to say that a painting by Tyndall, which unleashes the history of painting and related critical theory without slavish dogma, is a carpentered thing. The first painting to be seen in the exhibition is the last. A pun on the Phaidon art tome, Painting Today, Tyndall’s reads Pain Thing Today. Not only is this a darkly funny reminder of the difficult practice of art, but it also reminds us of Thing Theory’s relevance to Tyndall’s work: things delight us, ideas make us sick, and as Leo Stein said, "Things are what we encounter, ideas are what we project." Beware projections.

.jpg)

In the survey show, curated by Doug Hall, all Tyndall’s paintings are hung with double black wires, Salon-style, accentuating the stylisation of the gallery space and emphasising the object is detachable. Not a frame, but a frame with two prongs. The paintings are not just temporarily attached to the wall but to our preconceptions, our cognitions and expectations (knowing and being). Tyndall’s texts and habitual yellow patterns are familiar but also emergent, moving, contingent. So this means that whilst Tyndall uses imagery that is recognisable or knowable, it functions in a disruptive way over time. Tyndall adopts another icon for his storehouse, that of the unfinished 'S’ or figure eight. Is this meant as a symbol of infinity? If so, it countermands/balances his use of the skull image as an interpretation of human finitude.

.jpg)

You might describe Tyndall’s approach as radical orthodoxy, basic principles of belief which subvert the treadmill of cultural habits. This proposal recommends that when we walk up to a Tyndall painting, of a cartoon-like superhero using his powers of X-ray vision to look at something beyond the canvas, we step back to consider. We know, from Tyndall iconography in a thought bubble, that the super hero is looking at a painting. We are reading the information that is specific to the experience, rather than accumulated from wider cultural triggers. In this way we participate, or as Barbara Bolt describes, we contribute, by our looking, to the performative nature of the artwork. I am loath to slavishly ‘read’ his paintings (despite the risk of entering into philosophical pedagogy instead) because they are not a school test and they are not an invitation to an exclusive post-modern reading group. In fact, his iconography is accessible: retro family scenes, Munch’s scream, cartoons. All Tyndall asks of us is to look outside the habitual and anthropocentric modalities of being and to become conscious of looking, when we look.

Writing about Tyndall’s work, like the art itself, is an individuation but is meant as part of a whole, an acknowledgement of a larger system, of a praxis that might run parallel to theory or intellectualisations, rather than in opposition. If Tyndall’s interests lie in being, then philosopher Ian Bogost’s quote applies: “theories of being tend to be grandiose, but they need not be, because being is simple.” This relates to Heidegger’s primacy of experience. The meaning of preconceived being slips away, so it is good practice to follow Tyndall’s example and bring attention to the material reality of what has been made.