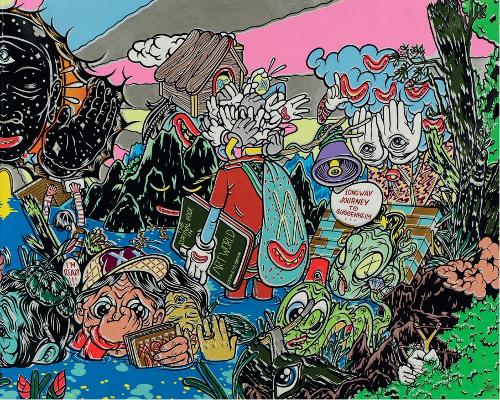

Adelaide Central School of Art graduates Claire Marsh and Fiona Roberts finish an illustrious 2012 with the opening exhibition in the apocalyptic The End series at DIY art space Format. The Beginning Of The End considers human response to trauma, and Marsh and Roberts’ works of fragility, illusion, surrealism and the grotesque are both poignant and masterful.

Roberts’ curiously unsettling In Knots is a small sweep of brown hair, not unlike a woman’s ponytail, that emanates from an open mouth, frozen in movement, at its crown. The deeply human yet physically impossible hybrid creature that lies on the floor of the space evokes both wonder and unease, raising questions as to what can constitute humanity - at what point does a collection of disparate parts become a being? How much of a body can be lost or rearranged before becoming something ‘other’?

Similar questions are evident in Marsh’s Crux, which anchors the exhibition, much in the same way her piece Shelter helped anchor the 2012 Waterhouse Natural History Art Prize. Where Shelter’s patchworked fur formed a clam-like vessel big enough for a person to curl up inside, Crux is a closed form that lazes on the floor. Kangaroo fur is stitched and compiled to make a new, hefty beast whose only identifying features, aside from the faceted fur, is a grid of four breast-like forms at one end. It’s a curious thing – docile, maternal, difficult to connect with and yet inexplicably inviting. There’s an overwhelming urge to touch, stroke or embrace the form, perhaps to see if a connection with living energy will rouse it, or simply confirm its dormancy. A befitting companion piece is Cloven, a pair of high-heeled shoes adorned with a voluminous fur covering. At first glance the shoes appear to be carved from bone, with marrow and dirt remaining in cavities etched into the sole. Yet the floorsheet reveals the true material – they are regular shoes covered in beeswax, and are a testament to the craftsmanship of the artist.

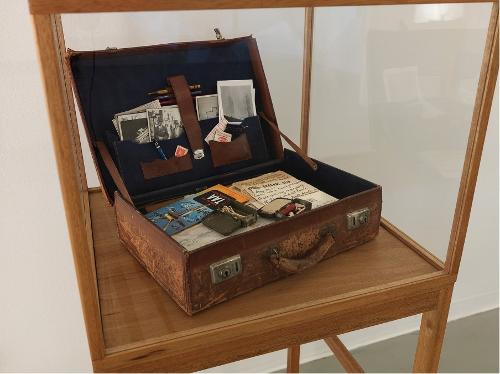

In contrast to Crux, Roberts’ installation The End legitimately invites interaction. A large maroon leather-bound book and two white gloves sit atop a small wooden desk. The book is a weighty tome, perhaps a thousand pages or more, and its title is simply The End. It’s ominous and clean. Who dares to open it? Those that engage in the glove-donning ceremony are met with page after page of the same message: “This page intentionally left blank.” Here, free will and determinism collide within a piece that is at once both disappointing and relieving, although many will not be brave enough to engage with the work – not out of fear of learning their fate, but out of its position in an exhibition whose delicacy of both subject and object seems almost certainly off limits to wandering hands.

Particularly delicate is Roberts’ In Pieces: thirteen small white ceramic busts arranged on a shelf. Each has a head injury – removed, split, cracked, severed – with the now separate parts suspended by wire to reveal blood red flock at the site of their disconnection. Clinical in presentation, their disconnection from trauma is both physical and metaphorical. Nearby is Roberts’ second ceramic piece In Vain, where an arm emanates from a jug that is held by its own hand in a looped response to the finite. The circular piece builds on the finality and hopelessness of the thirteen broken forms and delivers a different kind of purgatory through an infinite quandary.

Finally, a video work projected the full width of a wall: Marsh’s Hive. A swarm of bees crawl through holes in a damaged deathmask. The dull, industrious buzz of the insects fills the gallery but does not intrude; their insistent drone is not unsettling until matched with their grotesque movement in and out of the nose and mouth, creeping, buzzing and commanding a being that once was. Control has been relinquished; pain and discomfort is now for others to contend with.

Under the curation of Adele Sliuzas, the seven works are a humble whole. The sum of the parts is only marginally greater than the profundity of the individual works, but there’s a confident stillness in the space that’s unusual. Often the upper floor of Format is full to capacity with colour and novelty, or is at times tenuously conceived and hastily executed resulting in a disappointing emptiness. Here, care, consideration and skill is high in artists and curator, and Sliuzas makes the small exhibition seem large in the structurally ramshackle space. Each work invites viewing, but with qualifiers, like the way one might invite a young child into the room of an ill grandparent: “Come quietly, but step lightly and breathe deeply. Remain wide-eyed while ours are averted. This is the beginning of the end.”