As Australia, and the rest of the western world, are grasping to get a piece of the Asian cultural pie, the Asia Pacific Triennial (affectionately referred to as the APT) continues to hold its head high as the only major exhibition series in the world focusing exclusively on the contemporary art of Asia, the Pacific and Australia. This is my fifth APT experience and one that remains a must-do event, no matter the hype. Australia's place within the Asia Pacific region is frequently measured in economic and political terms, however it is the arts and culture of these regions that Australia has actively engaged in for the past two decades. The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art marks the 20th anniversary of this brainchild of Queensland Art Gallery (QAG), now shared with Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) next door, offering Australian audiences yet another window into potentially unfamiliar contemporary visual arts and cultures from the region. The offering is vast and APT7 includes just over 200 works, including some 40 new commissions, from 75 senior and emerging artists or artist collectives from 27 countries framed by geography - from Iran, Papua New Guinea, Japan, Indonesia and Australia – and artworks that deal through narratives with issues of conflict, migration and reconciliation.

APT is developed by a larger in-house curatorium, with this edition being lead by Russell Storer, Head of Asian and Pacific Art at the Queensland Art Gallery. While APT7 perhaps lacks the 'wow factor’ as in previous editions, it exchanges it for a quieter suite of contemplative works that have the genuine ability to engage audiences in the narrative of the artist and the work. Part of this shift is reflected in the archive project marking 20 years of APT, titled Ideas of the Archive. While exhibiting the ‘archive’ remains fashionable, the approach here is through collaborative presentations of the ‘archive’ rather than as a retrospective and draws on archives from the region, including APT’s own, and invited artists as miners. Hong Kong based MAP Office generate an atlas from the Asia Art Archive; India’s Raqs Media Collective archive the Sarai research centre in Delhi, and Singapore based Hemon Chong compiles a soundscape ‘room’ that includes voices based on texts from APTs 20 year archive. You enter the cavern room via a doorway that has been roughly punched through the wall. The space induces anxiety in its presentation – painted symbolically red, with carpeted surfaces, yet is meditative and somewhat soothing.

Complimenting the curated exhibition program is a film program curated by Cinémathèque, including an impressive retrospective of Chinese animation since the 1930s and the anticipated Kids APT that doesn’t disappoint with its interactive works and installations commissioned from selected participating artists. The opening weekend saw a full program of artists, curator and commentator floor talks and panel discussions that explored artist encounters, experiences and observations. While this will continue for the exhibition duration, the opportunity for visitors to discuss concepts firsthand with the artists on the opening weekend is invaluable. APT7 encompasses a number of themes, rather than one overarching theme, an approach that while criticised for being populist, suitably compliments the diversity of the region. In recent editions, APT has pushed the defined geographical boundaries of what the Asia-Pacific region is, and APT7 continues this as it explores specific aspects of the Asia Pacific region, particularly through two co-curated projects from Papua New Guinea and West Asia. Co-curated by Istanbul-based November Paynter, 0 – Now: Traversing West Asia, considers shifting borders, transforming landscapes and volatility of place, and exhibits works by seven artists and collectives from Middle East and Central Asia.

The second project, co-curated by architect Martin Fowler explores works from PNG, incorporating a suite of ceremonial objects from architecture to performance masks and costumes. Upon entering GoMA, visitors are confronted by a large ephemeral PNG spirit house facade intended to immediately confront the visitor. Its intention is to provide a window into the role of the spirit houses, where men are initiated, disputes resolved and art and music created yet women not allowed. Its intention is also to make us consider how the built environment influences our engagement with our surroundings and connection to place. However, its positioning, off to one side, fails in its intended impact and it becomes more of a decorative backdrop utilised for photo opportunities and performances; perhaps a part of its role in reality for hungry cultural tourists? It is the remaining exhibition of PNG performative objects (masks, costume, carved sculptures) from New Britain and the Sepik, occupying the entire GoMA Long Gallery, that are breathtaking and inclusive in their display, which effectively redeem my initial thoughts, and as intended does transport me to this ‘other’ place. Both co-curated projects reinforce a principal APT7 theme of looking at the speed of urbanisation, observed in the focus on ‘temporary structures’, both symbolic and architectural.

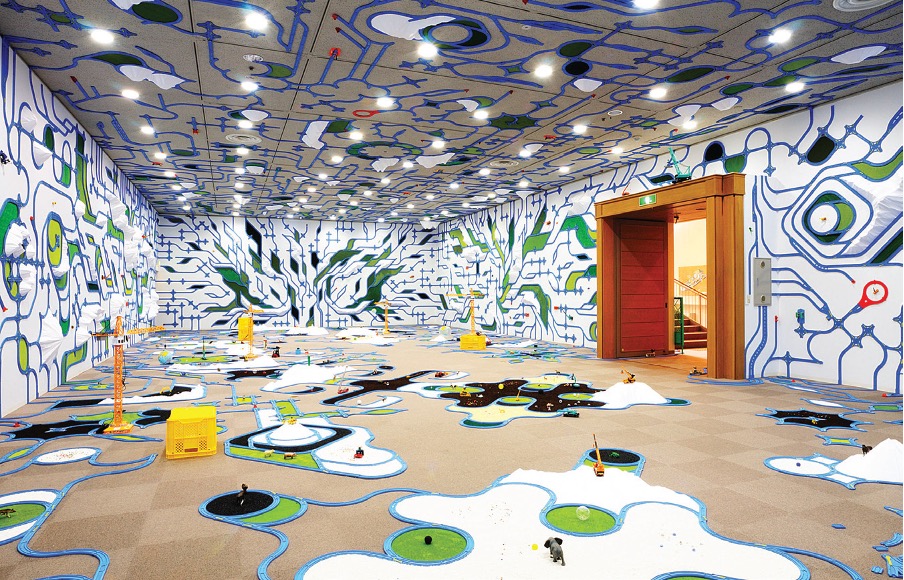

Japan, 2010. Photo: © Paramodel.

The unrelenting speed of urbanisation in Asia and its effect on society, landscape and economy are demonstrated in some key Triennial works. The satirical cartoon-style paintings by Indonesian Uji Handoko Eko Saputro (aka Hahan) provide commentary on the state of the current Indonesian art market, with a style reflecting Yogyakarta’s thriving graffiti and mural culture, while the sublime hyper real photography of Edwin Roseno (Indonesia) in his Green supermarket’ series (2011-12) reflects on the uncomfortable convergence of rural, urban and global influences on daily life. The accumulative ‘map’ installations of Japanese-based Paramodel borrow from the rise and rise of plastic toys as they humorously reflect the plumbing or underbelly of the cityscape and the search for the ideal city in Paramodel joint factory (2012), while the melancholic video work Cloud Island (2010) by Fiona Tan (Indonesian/ Netherland) captures a small Japanese community in a state of transformation and the mesmerizing Disappearing Landscape – Passing II (2011) by Taiwanese artist Yuan Goang-Ming satirically invites a very personal change of state.

One resulting outcome of urbanisation is of course migration, shifting boundaries and an urgency for recording the past. Indonesia/Australian artist Tintin Wulia encourages visitors to take a chance on redefining their identity. In a series of Arcade Game machines equipped with metal claws, reminiscent of the soft toy/prize games, the visitor can 'win' a new passport. Eeny Meeny Money Moe (2012), includes passports derived from the 10 richest and 10 poorest of the 192 member States of the United Nations. Wulia’s passport works began in 2007 and explore personal histories of familial migration; a timely work given the rise of displacement in our contemporary society. Other artists exploring the effects of migration are Louisa Bufardeci (Australia) who builds on her ongoing interest of boundaries, both real and invented, and by Vietnam-based Tiffany Chung who is herself part of a large Vietnamese diaspora post American-Vietnam War and for APT7 reflects on the fragility experienced in this undetermined journey as she presents 4,000 glass animals migrating to an unknown destination.

The excess of Atul Dodiya Meditation (with open eyes) (2011), documents migratory journeys through history in this series of 9 cabinets filled with layers of found drawings, figurines, photos, objects and imagery from André Breton to Ai Wei Wei, Gandhi to Warhol. In his artist talk, Dodiya poetically referred to this work as a collection of gems and pebbles, as if collected on the banks of the Brisbane River. The influences are many and continue to unravel for visitors who will make their own connections. Mention must also be made of the ethereal Reflection Model (Perfect Bliss) (2010-12) by Takahiro Iwasaki and the fantastical bejeweled paintings by Raqib Shaw that offer hybrid imagery from various eras and cultures – from Renaissance to Chinese kimono and cloisonné techniques. And for the wall-based sculptures, steeped in fairytales and mythology, by Rina Banjeree created from found materials close to her home. APT is popular. APT7 allows a space for Australian audiences to consider and reconsider their place in the world, to relax and embrace contemporary art, to reinterpret exhibited artworks through child’s play and to participate in the international art community and celebrate its enormous and unique capacity to generate provoking conversations.