A World Between: A Survey of Prints by Milan Milojevic retrospectively traces influences and technical developments in the artist’s oeuvre. Coinciding with Milojevic’s retirement, this exhibition celebrates his contribution to the Tasmanian School of Art where he completed his studies in 1976 and has subsequently taught generations of printmakers.

A profusion of flora and fauna evolve and mutate in Milojevic’s prints. A duck-tailed beaver and two-headed boars inhabit a tangle of briars and blossoms. Mongrel dogs snarl and scavenge in an instinctual bid for survival. Seething tentacles of coral and anemones multiply exponentially across a papered wall. These bizarre life-forms proliferate in spaces where the real and the imaginary slip between worlds.

Milojevic’s art practice has been influenced by both the expanding field of printmaking and his experience growing up in a first generation post-war migrant family in Tasmania in the 1950s and 60s. The suburbs of Hobart, shadowed by Mount Wellington and wilderness populated with platypi, wallabies, snakes and tigers, were a long way away from his parents’ European homeland. Before Milojevic’s father immigrated to Australia in 1946, Djoko had experienced the horrors of war and incarceration in Germany as a Serbian soldier. Young and optimistic, after a stint at the Bonegilla Reception Centre in Victoria, he worked on the Tasmanian hydro-electric scheme in the central highlands. He married Anna Grassl, who had emigrated from Germany, in Hobart in 1951, and Milan was born in 1954.

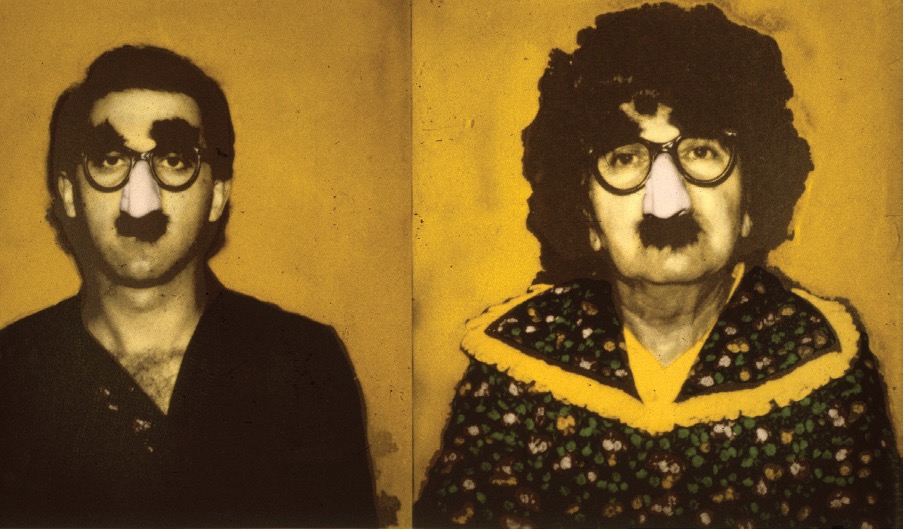

In the years around the Bicentenary of Australia Milojevic contributed to the national debates on multiculturalism and racism. Drawing on personal experience he interrogated relationships between cultural heritage, identity, dislocation and assimilation. The screenprint Portrait with Mother (some people say we look alike) (1983/4) depicts the artist and his mother posing, as if for identity photos, wearing Groucho Marx glasses with big plastic noses, moustaches and thick eyebrows. The image critiques racial stereotyping while uncannily revealing family likeness and genetic inheritance.

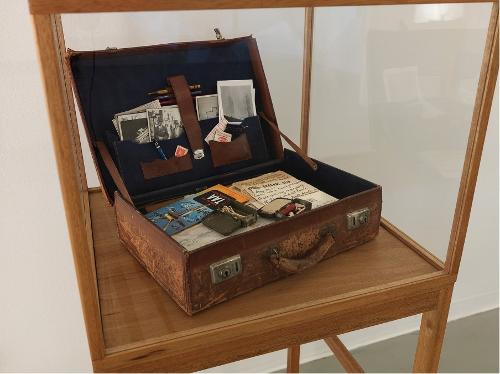

Milojevic’s father died when the artist was ten years old. There is a hint of nostalgia in Absorption/Assimilation, 1986, a series of lithographs that incorporate photographs from his father’s collection. Beautiful Balts, 1988, reflects on Australia’s rush to ‘populate or perish’ and the influence of eugenics on the provision of assisted passage for some, including the artist’s parents, while excluding others. In Arrival, 1990, Djoka and Anna’s passport photos are juxtaposed with an image of a communal shower, indicative of the degrading conditions that many migrants were subject to in the overcrowded centres. Perhaps the most poignant of this group of artworks are lithographs titled Dragi moj Doko (My Dear Djoka), 1991. Inspired by the idea of postcards, cut-out photographs of Djoka are awkwardly superimposed onto pictures of places he had been and things that he wrote home about: the Bronte Park workers’ camp and the massive hydro-electric pipes, a modest suburban house in Hobart and his motor car.

Beasts appear frequently in Milojevic’s work after he undertook a number of residencies in Scotland. In response to the bitter ethnic conflict in his father’s homeland in the 1990s Milojevic made several etchings of ferocious animals. Representing the havoc of war and embodying bestial aggression in An Affair in the Balkans, 1992, and Apocalypso/Calypso, Part 1 & II, vicious dogs, Tasmanian devils and boar-like creatures stalk terrain that stinks of rotting fish and death.

Inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings, Milojevic created a bestiary including a winged stag; a pair of Kilkenny cats that, according to Borges, were so savage that after they fought only their claws and tails remained, and a platypus. Milojevic stated that these hybrid creatures provided a metaphor, “to investigate my own identity - that of a first generation Australian of Yugoslav descent. The zoological displacements and dislocations of these images reflect geographical, historical and cultural displacement”. ‘Hybridity’ also described his approach to printmaking in which he integrated traditional methods with new media.

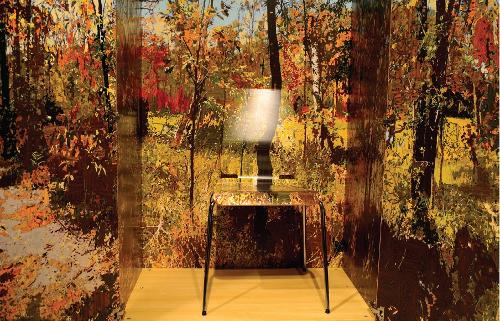

Using iridescent colours and digital technology Milojevic invented new microcosms surging with passion. Animal characteristics that give a competitive advantage to the struggle to kill and reproduce – beaks, claws, antlers, feathers, talons – are everywhere apparent. Alluding to scientific speculation about the diversity of life, in Tree of Birds 2, 2011, a winged puffer-fish, a dove feathered with petals, and a lizard-necked hawk are perched on a sprig under a bell-jar as if specimens in a natural history museum. In contrast to the vigour and implicit violence in most of the images, Topiary, 2011, is passive and bleak. Bland shrubs appear to have been genetically manipulated to produce a chillingly homogenised ideal of perfection. In these worlds between worlds Milojevic has created speculative spaces of resistance and wonder.