Making definitive statements about the historical significance of current artists is a weighty task; one cannot deny the role of individual voices in determining what remains for posterity and what is forgotten. One voice operating at the juncture of documentation and history belongs to Katie Lenanton, curator of HERE&NOW12, an exhibition and artistic program featuring early career Western Australian artists and their activities. The project introduces a young generational stratum seeking to consolidate the industry around them, at a time when established commercial galleries are passing the baton and traditional skills are vanishing.

Satellite events at Perth's most ambitious and promising artist-run galleries (OK Gallery, Galleria and The Museum of Natural Mystery) run alongside a nuclear exhibition at Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery. Featuring artists Clare Peake, Jacob Ogden Smith, Ben Kovacsy and Tom Freeman, Lenanton’s show provides a finely tuned examination of the culture that defines this group, and perhaps early career artists more widely. Without succumbing to manifesto, the exhibition privileges values like continued learning, self-sufficiency, and elaboration on past traditions.

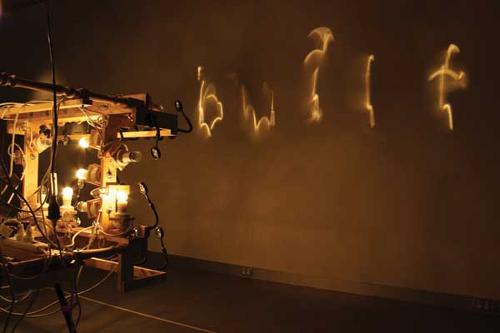

Jacob Ogden Smith has built a practice on disappearing process-based skills. His installation Olsen Fast Fire Kiln, Hovea, Western Australia is a plywood recreation of the ceramics kiln upon which his tutelage under master potter Greg Crowe centres. Six screens are set into the sculpture, depicting the blaze and crackle of interior flame. As an interactive model lacking the perilous heat of a real kiln, the work enables Smith to pass on knowledge about fading ceramics processes like woodfiring.

As schoolchildren engulf it, falling upon the screens and guessing how to get inside, it’s clear the work is pedagogically active: a shrine to the transferral of intergenerational knowledge. An honours graduate in the last year before Curtin University dissolved its ceramics department, Smith’s appetite for conserving tradition is acute.

Ben Kovacsy’s marquetry sculptures employ skills even scarcer in the gallery. For small-scale series Off Cuts, complex triangular arrangements of beech, jarrah, she-oak and walnut woods are whittled into tree-trunk shapes. Waiving nostalgia, Kovacsy’s work develops woodworking traditions to participate in trending visual conventions - geometric pattern, wood veneer and visual pun. The precision and material integrity of woodwork is repurposed for a world where plastics, mass-production and flat-packed furniture have sidelined decorative carpentry.

A representative of the multidisciplinary zeitgeist, Clare Peake’s Eclipse works span glassblowing, ceramics and drawing. On a table, 12 lopsided glass vessels are paired with uncoloured clay tubs, impressed by Peake’s fingertips, seemingly inexpertly, perhaps deceptively so. Along the wall, Peake’s drawings are labored pencil rings with imperfect edges where solo lines escape the bulk of an otherwise Fort Knox-like, metallic ring of graphite residue.

Each work is made by repeating single motions, between which irregularities appear and learning occurs. Peake’s idea about the right kind of roundness changes, as does the next resulting form, however in their order on the table and around the room no improvement is evident, rather confirmation. The works are simple, similar, as though produced merely to practice Peake’s hand. Even the glass works, fabricated by a studio according to her instruction, do not approach an ideal form, but instead imply precision by the sum of their parts.

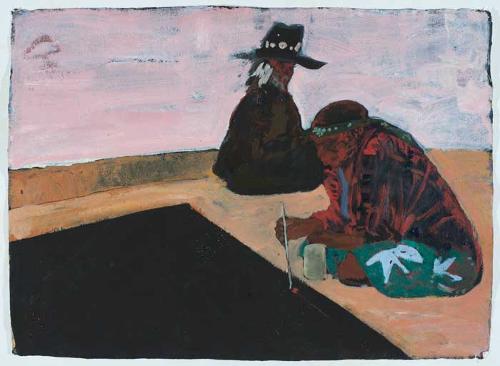

Tom Freeman’s Church Window paintings feature architectural motifs he collected whilst tracing his parents’ early lives in the East English town of Peterborough. In pallid, climactic glazes, Freeman translates stained glass designs onto large, window-sized boards. His line work is notably uneven, the painted patterns nudging and bleeding into one another in a manner as human as the family history they map.

A recorded interview with Freeman’s grandfather plays nearby, the sound obscured by echo and distortion as though overheard from a distant cathedral pew, mediated by the acoustics of a cavernous vault. Like Freeman’s windows, the interview is a repository for personal history, which in its translation becomes partial and begins to resemble aesthetic pattern rather than narrative.

In its gentle elegance HERE&NOW12 sidesteps the pitfalls of other surveys of early career artists: annual meet-and-greets or graduate exhibition meat markets. Lenanton introduces these artists (or translators, or preservationists) not as an exclusive group, but as indicative of an ethos incorporating diverse emergent practices and bold initiatives to support them.

These are not glamorous trailblazers, but navigators traversing an industry they have carefully studied and wish to nurture. We might call them infrastructuralists; self-consciously responsible for smoothing the transition between emerging and established, sourcing space, funding, publicity, skills, forging relationships and generating optimism. Part of this ethos herself, Lenanton has a sound historical voice, selecting a remarkable group of artists to illustrate her cultural account of Western Australian art.