Tales Within Historical Spaces is a combined collection of sculptural, photographic and painted works by Polish-born artist Beata Batorowicz from the last 10 years. The pieces are entrenched in Batorowicz's childhood memories, her Polish heritage, and her own fantastic personal mythologies. Armed with her knitting needles, leather thonging and fur, Batorowicz weaves together an enchanting narrative of fiction and family history which twists and turns like the tales of the woodland creatures she creates. This curious artist draws upon the book Tales from Auschwitz, a collection of stories illustrated and smuggled out by the Polish inmates of the notorious prison in WWII. This is combined with the experience of Batorowicz’s recent visit to her Polish Grandmother, where she spent time recording many of her family stories, in particular those about WWII. Enter the woodland world of Batorowicz, where she becomes the trickster, the naughty fox and the metaphorical daughter of Joseph Beuys, a world that is like a memory made up of fragments, where boundaries of time and reality, culture and myth are blurred.

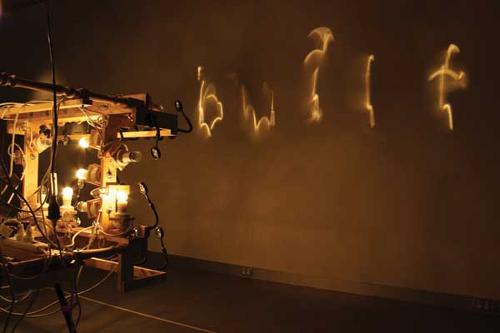

The pieces that make up the staple of the exhibition are Batorowicz’s laboriously handcrafted sculptures. In Hedgehog (2012) the animal sits up on its hind legs in an inquisitive gesture. It peers up at the piece on the adjacent wall, a fox mask entitled Trickster (2011-12), and the two appear to be in some kind of exchange - perhaps the archetypal moment where the naïve woodland creature meets the deceptive fox. In another room, The Tricksters Tales (2010) hang 3 large leather-bound tails of animal-fur and knitted leather thonging, draping from a belt across the floor. In conversation Batorowicz speaks of this work and of Trickster’s Mask (2010) and Trickster’s Canister (2010) as though the viewer might "wear them and activate them, because that’s what the Trickster does".

It is difficult to avoid being seduced by the texturally indulgent craftwork that tempts towards tactile engagement. Interspersed between the sculptural works are intricate prints, paintings and photographs depicting the wintertime landscape of Poland and the forests of Wroclaw, the woodland home of Batorowicz’s fairy-tale creatures. The exhibition speaks of her journey over the last 10 years, and the rooms of the gallery play out in a circular storyboard manner. The first sets the scene, with darkly painted walls and brooding forest pictures, encountering characters such as the hedgehog. In the second and third rooms, we learn about the nature of the trickster herself by her disguises. We are also taken into the artist’s personal world by a series entitled Grandmother’s story (2011-12). The final room features an enormous pair of knitted braces that occupy all of the available floor space. It’s a fitting end, as Daddy’s WWII Braces (2003) are frayed at the edges, appearing to be chewed away by rats. For Batorowicz, the braces are a mark of time, and as the rats chew into the braces, they are chewing into history, gnawing into her past and eroding away her memories.

It’s an interesting moment, the space where fact and family history meets childhood memory, fiction and fantasy. It’s a world where Batorowicz speaks of herself in the third person, holds a number of different personas and spins her stories with twists of fate. Her imaginary re-interpretation of her childhood parallels that of her metaphorical adopted father Joseph Beuys. The works make strong reference to each other; in particular by Batorowicz’s use of the colour red. Not only is it a reference to her Polish heritage, it is the colour of healing, and the colour of the Red Cross which can be found on many of her works, such as Tricksters Tales (2010) and Little Fox (2010). Batorowicz subverts the well-known story of the healing of Joseph Beuys by the Tartars, by references within her own works using fur, which she claims “as a kind of healing for herself”.

Engaging with Batorowicz’s works opens layer upon layer of meaning and raises a multitude of questions. She examines the role of the crafts ('little art’) and critiques what she calls ‘Big Daddy art’ – a reference to the male-dominated history of Western art; and provides personal insights into war, hope, resistance, family and identity. The nature of this exploration is very much like her stitching, thickly woven from many different materials. It takes time to unpick the stitches of this sneaky trickster, and get to know her ways. Although she is elusive and cunning, it is clear that this little fox is on a brave mission. In Tales within Historical Spaces Beata Batorowicz speaks with a compelling voice that traps all audiences in its curious web.

Rainer Doecke