This year's Shanghai Biennale, subtitled Re-Activation, represents a turning point in the city’s cultural life, and is less about the artworks or curatorial vision of the exhibition and more about the 'soft power’ aspirations of a rapidly developing nation. While the previous eight Biennales were held at the Shanghai Art Museum, the current iteration is the inaugural exhibition for Shanghai and Mainland China’s first public contemporary art museum: the Power Station of Art. The newly renovated building is massive, and contains 40,000 sq meters of space, with between 9,000-15,000 sq meters devoted to exhibitions. As is common in China, it is a show of power through architectural scale.

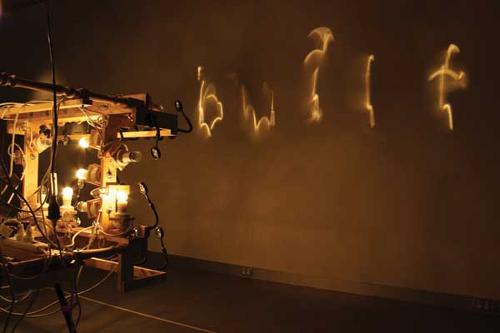

Reflecting the Biennale’s reincarnation in the Power Station of Art, Re-Activation explores how artists galvanise and transform energy and resources in their practices, be it physical, social or intellectual energy. The show also includes City Pavilions, some within the Power Station, but most in alternative spaces, churches and unused retail spaces concentrated in Shanghai’s North Bund area. Curated by Qiu Zhijie, one of China’s most prominent artists/educators/curators, and co-curated by Boris Groys, Jens Hoffman and Johnson Chang, the works are too disparate and numerous to effectively convey the Biennale theme. The Power Station of Art feels particularly jumbled, and yet certain pieces and sections of the exhibition stand out enough to make the show worthwhile.

One such work is Huang Yong Ping’s Thousand Hands Kuanyin (1997-2012), a 180-meter high sculpture that greets audiences at the museum entrance and resonates beyond its sheer size. Here the artist appropriates Duchamp’s readymade bottle-rack and transforms it into a spiritual monument. By hanging thousands of Buddha hands holding everyday objects on the rack’s protrusions, the readymade loses its sexual edge and becomes a version of Kuanyin, the thousand-armed Buddhist goddess of compassion. On the second level, amidst a cacophonous grouping of works, sits a portion of Danh Vo’s We the People (2012). Here Vo creates a version of the Statue of Liberty using the original fabrication method, building the piece in segments from a metal framework cloaked in thin copper sheeting. He then leaves the sculpture in fragments on the floor, and the work becomes a haunting evocation of a fading ideal.

As much of the exhibition showcases large-scale sculptures and installations, which quickly grows tiresome, Olga Chernysheva’s contemplative video work Clippings (2008) is a welcome shift in temperament. The work is about presence, and is comprised of simple everyday images and short videos paired with evocative texts. While not radical, the piece stimulates a sense of mindfulness in the viewer. Another notable video is Nira Pereg’s work Abraham Abraham (2007-2012), a documentation of caves holy to both Muslim and Jewish worshippers. Normally the site, which is claimed by both religions, functions as eighty percent mosque and twenty percent synagogue, but for short periods during the year and under Israeli army supervision, the caves are fully occupied by one faith. The video records this temporary conversion, and as torahs are covered by sliding doors, and Muslim prayer rugs are set down, one witnesses both the intensity and the malleability of belief.

On the museum’s top floor, the City Pavilions begin. This curatorial decision seems arbitrary and disappointing, as the majority of city projects occupy off-site spaces within Shanghai and feel more intimate in their alternative settings. However, the Mumbai and Palermo pavilions, both housed in the new museum, are worthwhile. The Mumbai exhibition exudes a sense of materiality and process. Works made out of jute, rubber bands, newspaper and concrete give the space a visceral feel; their abstract qualities particularly resonant against the backdrop of Pablo Bartholomew’s candid black and white photos of Mumbai, made between 1976 and 1983. The Palermo pavilion has a lovely arrangement of pieces, romantic yet strong. One can sit in Lee Kit’s little café set-up, which has paintings but no coffee, and watch news-clips of Pina Bausch’s work and experience in Palermo. In Manfredi Beninanti’s installation, The Sun Goes Dim While the House Lights Up, a secret little window looks into an elaborately decorated, 18th century styled study, the scene sparking imaginary narratives. Guo Hongwei’s A Page of Ocean, a sheet of thickly built-up acrylic painted to resemble the sea, conjures up a portable Mediterranean. Overall it was a pleasant make-believe trek to this Italian port town.

If the Power Station of Art is the corporate headquarters of the Biennale, the remaining City Pavilions, held in sites around Shanghai, thankfully feel like mom and pop art shops. Meandering from space to space, encountering the works in this way felt like an act of discovery, and these projects lend to the Biennale an air of freshness that is lacking in the main exhibition hall. One such location, the Central Mall, houses fifteen pavilions. The space, built in 1930, still retains charming moments of its original architecture even though it is currently gutted, and in its raw state it exudes potential energy. The Detroit pavilion Voice in the City (2012) fits perfectly in this setting. An extraordinary collaboration between local performers, dancers, artists and musicians created a soulful portrait of this municipality by enacting a montage of its stage history: from Vaudeville through to Soul Train. In the LA pavilion, Walead Beshty found and displayed in plexiglas vitrines, six different fakes from six different Chinese factories of the same black and white Celiné Mini Luggage purse. The gesture seems a jibe at China’s propensity for fakes and Shanghai’s endless shopping culture, but it also investigates the politics of Intellectual Property rights and how counterfeiting generates cultural value.

Of all the city pavilions, and of the entire Biennale, the most heartfelt and affecting work was Pittsburgh’s project, Jon Rubin’s The Lovasik Estate Sale. With this piece the artist, in a direct and intimate way, represents the lives of everyday Americans living in Pittsburgh, their habits, hobbies and dreams. The Lovasik family epitomises a typical family that have occupied the same house in the city suburbs for generations. Rubin, coming across the family’s estate, purchased its entire contents, shipped them to Shanghai, arranged the objects in the manner in which he first encountered them, and then sold them to the Biennale visitors. While other pavilions represented cities, this project was a portal into one. Through knitted blankets, nativity scenes, family photos and model train sets, bits of Pittsburgh’s history and DNA were dispersed in Shanghai and the audience was fully engaged. Re-Activation did what it set out to do, setting a new precedent for art in Shanghai involving both a greater international and a greater local art world and art audience. It made me think, maybe, if you build it, they do come.