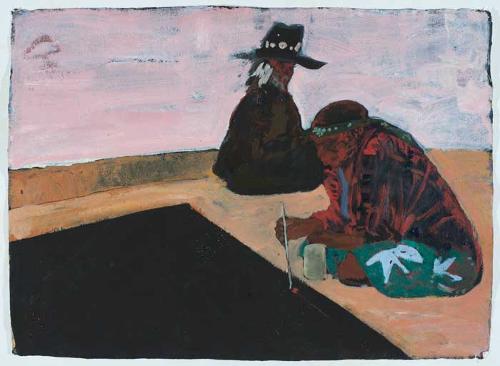

Queenstown epitomises melancholy. The poverty in this once prosperous mining settlement on Tasmania's West Coast is unmistakeable. Weatherboard houses with flaking paint, rotting fibreboard, corroded roofs, and roaming sentries of cats, line the perpetually damp streets. Visitors arrive via a winding and precipitous road through a fascinating orange moonscape dotted with small shrubs struggling to regrow after mass deforestation. The environmental regrowth could be viewed as a metaphor for the attempted reinvigoration of this town reflected in the recent three day Queenstown Heritage and Arts Festival. The festival coincided with the centenary of the North Lyall mine disaster, and it seemed as much a collective mourning as it was a celebration of place. It is within this context that Inflight ARI commissioned five site-specific artworks in conjunction with the festival, and with its distinctive landscape, cultural history and rusted ex-industrial structures, the town is a veritable goldmine for site-specific response.

Andrew Rewald’s series of gastronomic performances were ritualistic, interactive, and meticulous in detail, addressing aspects of Queenstown’s cultural heritage without resorting to nauseating sentimentality. As a practising chef, Rewald generously lured participants through food, recognising the centrality of meals to socialisation and community. In the first performance "nostalgia food", the artist served wallaby stew formulated from research on the eating habits of early Queenstowners. The second iteration “desire food”, required the participants to 'mine’ chocolate cake from a darkened shed, and his pseudo-religious Sunday “conceptual food”, sited in the disused United Church, referenced positive social change.

Comparatively the performance by Michelle Sakaris seemed somewhat unresolved and clichéd. The artist encouraged visitors to tie a knot in a 1100-foot long rope, representing lives lost in the mining disaster. While the sentiment appeared genuine, the presentation of the work was relatively ill-conceived, particularly in relation to the performance sites. For instance, on the first evening, she shared a marquee with Rewald, but while the tent and large vats of stew had key associations with communal consumption and thus his artwork, Sakaris’ performance seemed ‘plonked’ and out of place.

Peter Waller’s installation in the charred shell of the Royal Hotel just outside Queenstown, was easily the most visually powerful of the artworks. The wild blackberries at the base of the old dining room were replaced with water, with vertical steel rods extending from the now non-existent ceiling. The artwork changed with the weather, and when still, the reflective water surface seemed more revealing than the direct gaze. It was a subtle intervention and one designed to sit in dialogue with the space, rather than dominate.

Claire Krouzecky and Raef Sawford’s collaborative Perspectus comprised a series of projected images of the surrounding landscape in main street shop windows, ranging from subtly embedded images in the supermarket’s community notices, to screens that filled entire shopfronts. While the repetition somewhat reflected the dominance of the naked hills as the town’s prominent public image, the sheer number of sites was perhaps unnecessary.

Matt Warren and Darren Cook’s Still in the former West Coast District Hospital was reminiscent of Mike Parr’s 2008 Biennale of Sydney Cockatoo Island installation in that the viewer was forced to navigate the abandoned, once utilitarian, space. In these sites, empty rooms are just as important as those occupied by the artists’ interventions. The already fascinating space combined with an atmosphere of unease, meant that a balance needed to be struck between occupation and letting the building speak for itself. Unfortunately, the number of objects placed in this hospital space - piles of flour and sugar, teacups, rocks, false teeth, multiple television screens, lights and audio – was overwhelming, and although the installation was engaging I wonder if the existing mood of loneliness, abandonment and trauma could have been better reinforced if limited to its sound and light elements.

Lucy Lippard noted in The Lure of the Local: “for all the art that is about place, very little is of place – made by artists within their own places or with the people who live in the scrutinized place, connecting with the history and environment”. However the outsider status of these mostly Hobart-based artists seemed far from problematic, particularly as unlike many of the other festival events, most of the artworks avoided indulging in clichés or mythmaking. Instead, their artistic re-interpretations of Queenstown’s unique sites were communicated through universal themes such as community and change. The project signals a new direction for Inflight, which is aiming to produce more off-site exhibitions under its new name “Constance” and, based on this excellent Queenstown project, the expansion can only be a good thing.