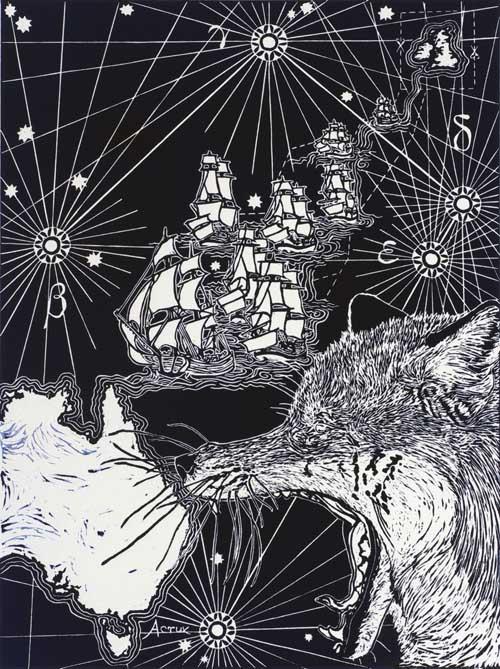

The 'environment' used to have the connotation of the great outdoors, serious weather (usually cold), and n-a t-u-r-e. That has long morphed into a more global, political morass. However there are vestiges of the earlier version in the art of places where those earthly elements still loom large. This is so in all sorts of Australian art of course: always in Indigenous art, then in settler imaginations and variously but still strongly since. And it also seems true in Arctic regions.

In a freezing November years ago, I travelled on the Trans-Siberian Railway across the thousands of miles of tundra north of China. Out of the samovar-heated train’s windows was the huge, unpopulated northern space, of muted colour and sparse vegetation. It could have been vast tracts of desert Australia, except in Russia you put your head out of the door and it snapped back from the sub-zero icy air. Both are powerfully confronting environments, emerging forcefully or latently in the art and cultural focus of their people.

Camouflage, Visual Art and Design in Disguise at Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, the sparkling new museum in the world’s "most northern capital", is testament to this specific environment. It doesn’t seep stealthily at you as some art museum displays do, but hits you bodily with its full fresh air. Helsinki is “World Design Capital 2012” and there is a well-crafted air to the whole city. Art Deco buildings are beautifully presented on every street, tended gardens, sparkling food, Marimekko, Arabia.

Camouflage as a title seems à la mode - with Artlink working with this title for a coming edition and a new book Camouflage Australia – art, nature, science and war by Ann Elias on the effort of Max Dupain and Frank Hinder to help the more literal war-related camouflage work in 1939. This show is about slips and elisions but so much art is about elision that the title is fairly unrewarding.

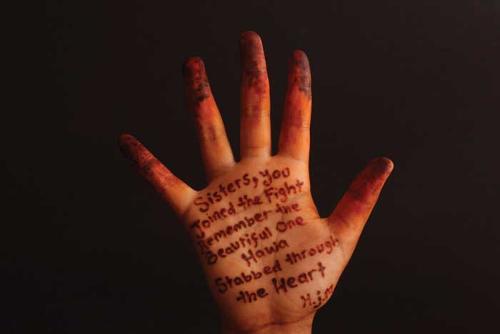

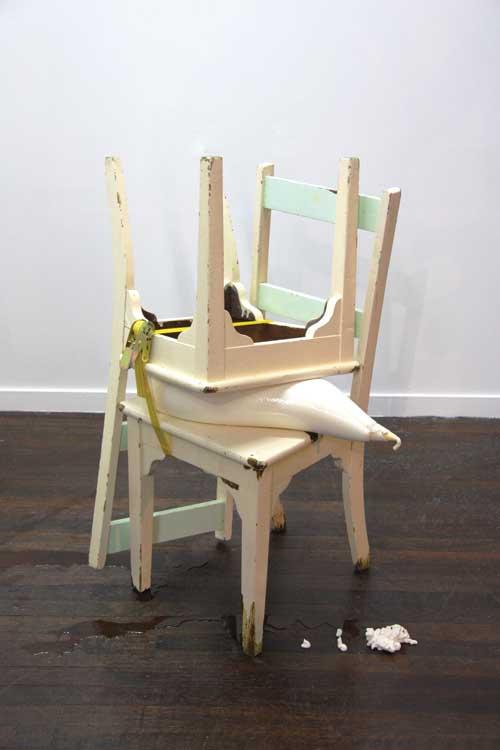

The exhibition does elide between art and design though and is one of the key shows of the Design year. It includes 19 international, mostly young, and mostly European artists, some working critically with design/craft elements: designer glassware literally shot with images, Russian lacquer-ware made anew, and a fabric spa-bath made to float in lakes. However, the stronger elision is to the older force of art and nature. Twigs, thatched hats, human leaves, taxonomy (especially with jewels – another global theme), leather gloves returning to live skin literally interweave with more mechanical offerings. Dutch artist Silvia B has made the well-behaved ladies’ gloves, displayed as at Harrods, but becoming both humorous and macabre with growths of moles, freckles and remains of scars and sutures. She asks: “would you wear another person’s skin, to carry his or her tattoos or moles?” We do wear of course (and seriously, in the Arctic, fur is the big deal) other creatures’ skins.

The central poster girl for the show is an old Norwegian country woman, close to Norse mythic beings from those fjords and forests. With twinkly eyes set like jewels in the face of an elf or wood-sprite, she wears a hat of woven twigs as naturally as her generation’s cashmere beanies. She is part of a series of portraits by Finnish Riitta Ikonen and Norwegian Karoline Hjorthin. Ikonen does a wonderful performance, shown in video in the exhibition, as a human leaf, a snowflake, a chantorelle (mushroom), and, most eccentric, a Baltic herring.

These had more resonance for me than the overtly political work on show (another sort of camouflage) and reminded me of the great Icelandic pavilion by Gabriela Frioriksdottir at the 2005 Venice Biennale which she turned into a mossed cave with elf spirits taking over, and which fittingly included a piece by Björk, as well as the series of work by Finnish Antti Laitinen at the 2010 Liverpool Biennale. I praised the latter work in an Artlink review (vol.30, no.4, 2010) and was surprised to learn that others were not so keen on this work – what was not to like I thought!

Perhaps it goes back to those long journeys across the Australian inland, trying to figure (as a non-Indigenous person) how to relate to it. How was I to make it as ingrained and natural to me as those elf figures of the fjords so obviously find their own harsh and beautiful land?