Outside my back door, spilling over the fence from my neighbour's yard, is a wisteria in full bloom, its chandelier blossoms - mauve, white to purple – moving slightly in the spring breeze. I walk out the door and my senses flood with that extraordinary scent and the frenzied sound of bees dipping in and out to claim the nectar. Despite the bees, I bury my face in the wisteria’s soft pendules, inhaling the scent fully. The sun is warm on my neck and through the blooms I observe the crusty muscular tangle of the branches, dappled in the filtered sunlight and busy with the activities of ants. Beyond, though less clear, this world of nature extends and continues its constant change.

In Elisabeth’s Kruger’s survey exhibition at the Drill Hall Gallery there is a room with five large paintings – one of irises and four of wisteria. These paintings are immediately arresting in the exquisiteness of their rendering. More importantly they are vessels containing a vast body of knowledge and experience – a perpetual contemplation of the world, past and present. Like the line of dancers in the last scene of Pedro Almodóvar’s film 'Hable con ella', the perfect downhill run of a skier, Richard Burton’s recitation of Dylan Thomas’ 'Under Milkwood', or the haunting song of Wilhelmenia Fernandez in Jean-Jacques Beineix’s 1981 film 'Diva', the paintings are fluid and seamless, belying endless experiment, experience, practice, observation and emotion that coalesce on the canvas.

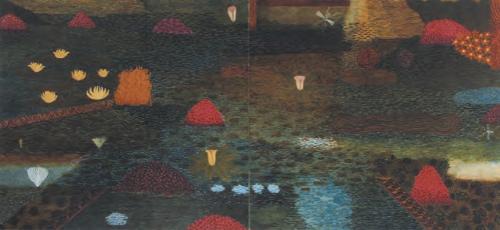

'On Beauty', curated by Jenny McFarlane, surveys Kruger’s work from 1988 to 2010. One of the earliest works 'The Last of the Cool Skies' (1988), a small gouache and synthetic polymer painting on board, won her the coveted Moët et Chandon Australian Art Fellowship in 1989 and marked a turning point in her focus. The two most recent paintings 'Sweep'(2010), a large portrait of a backyard vegetable harvest of carrots, beetroots, squash, peppers and basil, and 'Eau-de-nil' (2010), a smaller still-life of garlic and pears, indicate the garden as the central workstation for Kruger’s practice over the past two decades. Through observation and interrogation of the natural world in the garden, its fecundity and decay, its luxuriousness and intensity, its order and disorder, its life and death, she considers also the duality of human nature.

While the most dramatic works are the large lusciously painted canvases of flowers, fruit and vegetables, the exhibition also includes works from other series. 'Body' and 'Soul' both painted in 1994, set botanically detailed and finely drawn bunches of vegetables (body) and flowers (soul) against a dark earthy ground. They are beautiful and sombre. 'Without nerve, Nothing Need be Done and Out of the Wind', from the 'Asleep in the Garden' series of 1998, allow plant forms and human organs to mutually metamorphose producing strange, unsettling hybrids in moist, salmony pink and greeny tones. Similarly, the 'Blot' series (1998), that use the Rorschach blot as a starting point, 'Seen in a Vase' (2003), and 'Mirrored gul butterflied' (2001), use distortion to reveal surreal patterns. The general tenor of the exhibition is of flamboyance and potency. The colours are beguiling and compelling. The petals of the roses in 'Ballet' (2002), for example, hold such tenderness, and the sun-drenched grapes in 'Bunch' (2004), are so succulent.

But my experience of the paintings in this exhibition is necessarily entirely different to my experience of the wisteria outside my back door. With my face in the petals, my head full of scent and the warm sun on my neck, I am unencumbered, momentarily surrendering to pure sensation. The paintings, though they so expertly recreate the plant, demand our thoughtful attention. They are elaborately overlaid and infiltrated with interpretation and meaning and while they astound us with their beauty, they remind us of our responsibilities. We do not look through these paintings to the natural world beyond, but in them we see reflected our own psychological landscape. And as the artist has remarked: "The issue is not to render the natural world, but to raise questions and ideas about our relationship to it."