.jpg)

The first major exhibition to focus on Aurukun's contemporary art, the University of Queensland (UQ) Art Museum’s 'Before Time Today: Reinventing Tradition in Aurukun Aboriginal' Art took two years to see to fruition - and it shows. Thoughtfully curated and accompanied by a number of performances, talks, and a multidisciplinary publication, the show is rich and diverse. Inspired by connections between early to mid-twentieth century Wik ceremonial carvings held in the university’s Anthropology Museum and contemporary artworks being collected by the UQ Art Museum, the show is premised around the ways in which contemporary practitioners in Aurukun are making artworks that reflect a continuous ancestral heritage as well as increasingly sophisticated aesthetic and material innovations. Juxtaposing the older works with contemporary examples evokes a number of issues, not least the practice of collecting itself or the loaded quest of 'knowledge’ to which institutions such as universities devote themselves.

Moreover, as curator Sally Butler clearly articulates, the show deals with some of the thorny questions over tradition and change that often arise in relation to Aboriginal art. By displaying works that use extremely contemporary materials, 'Before Time Today' obliterates any preconceived notions of what constitutes ‘authentic’ Aboriginal art. As Butler aptly states: "Aurukun art is not ‘timeless’ so much as it is ‘time-complex’." Situated on the western tip of Cape York, Aurukun is home to the Wik and Kugu peoples, who are made up of five clans – Apelech, Winchanam, Puch, Wanam and Sara. While historically the area has been most famous for land claims (and the book includes a riveting chapter dealing with this), of late, it has become increasingly well-known for its thriving artistic community, with works achieving recognition in numerous exhibitions. Aurukun’s artistic hub, the Wik and Kugu Arts Centre, has operated in its current form for about ten years and is today presided over by Mavis Ngallametta.

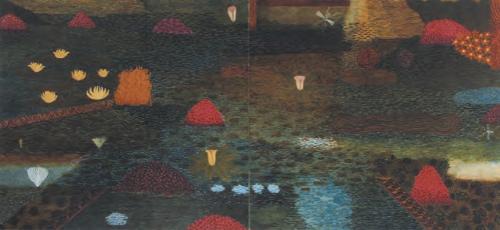

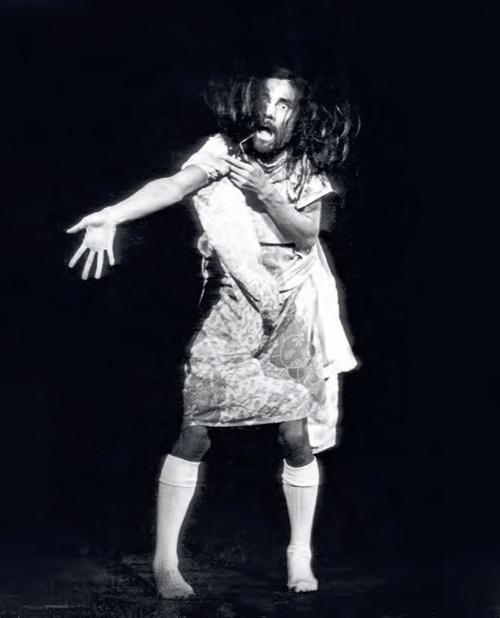

Mavis is represented in the show by a range of works which encapsulate the exhibition’s aims: her vivid canvas paintings marry intimately known experiences of the land with the artificial vibrancy of acrylic paint, while her woven baskets combine a traditionally learnt skill with the modern material of ghostnets (lost fishing nets collected from the tideline); both are resplendent in their eye-catching luminosity. Mavis was one of the many performers (which included Aurukun children who board at local Brisbane schools) at the opening event. I attended this event (one that was inadequately publicised, which is unfortunate since anyone who was there couldn’t help but be completely enthralled by the performers’ dancing and singing), and it was a perfect prelude to engaging with the artworks. For, entering the space afterwards, I felt as if the works literally became alive before my eyes. They seemed to brim with power, vitality, and a tangible energy. They hummed.

Seen in this light, much of the men’s work is overwhelming: Craig Koomeeta’s abstracted paintings of headdresses, Joe Ngallametta’s law poles, and Arthur Pambegan Jr’s striking canvases are all declaratory and physically commanding, inspiring respect as well as aesthetic appreciation. Clearly, then, these artworks are anything but static or ‘cute’ (as I’ve heard some people inappropriately term them). Furthermore, after seeing the publication’s opening pages, in which a stunning aerial shot of Aurukun depicts its black, white, and red sand shoreline, another dimension is added: the works’ intrinsic relationship to the land in which they’re made becomes so clear. And that synergy is mind-blowing.

On subsequent visits, I’ve continued to find the exhibition powerful and visually diverse but I wonder how much of my experience was shaped by the opening performances. While it is not possible to bring the Aurukun dancers out to the space on a regular basis, it would have been prudent for the organisers to more effectively incorporate this important element into the show. Admittedly, there is a video featuring Aurukun dancers on a small television screen as you walk into the museum, and some videos screening downstairs (a fact that I overlooked in the first three visits I made) that feature artists talking about Aurukun’s history (specifically, encounters with Dutch explorers) and about living in Aurukun. However, after visiting the recent AES+F show, which incorporated massive video screens, I am curious as to why more innovative audio-visual accompaniments were not further explored. A wall-sized image of the aforementioned photograph would also be a simple but effective addition to the show. Nevertheless, 'Before Time Today' offers an intelligent and refreshingly revisionist approach to a rich and complex area of Australian art.