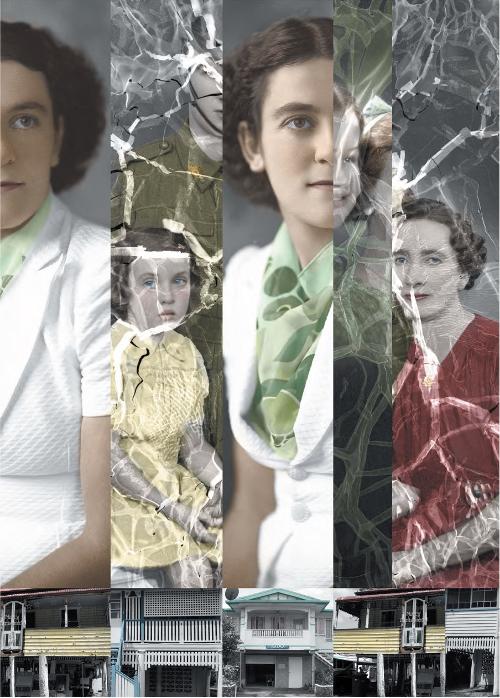

The curatorial premise of bringing Carol Jerrems together with photographers William Yang, Larry Clark and Nan Goldin was highly effective. Juxtaposing an Australian artist with synergistic international practitioners is all too rare. Jerrems already sensed that the balance of power in cultural authenticity was slipping in the 1970s. The parallel stories of other places and practices are rarely accessible to the general visitor in the public gallery. On these grounds 'Up Close' totally justifies the effort and resources that have been devoted to it. The multiple overlaps between the artists: photography, popular culture, sexual identity, sexual permissiveness, self-display and personae, the extended family and home offered by subcultures, the visual theatre of urban lowlife are persuasive as linking devices and informative social commentary.

The intellectual and visual assemblage of 'Up Close' delivers a tangible vision of life in certain places, in certain stratas, at a given time that is deeply fascinating. As a strategy for dealing with Jerrems and Yang 'Up Close' established a more meaningful and critically rigorous narrative than frequently devolved to their work and will offer a modality for its long-term and more reasoned appreciation.

The catalogue acknowledges the difficult moment in Australian histories of women and sexualities represented by Jerrems. The sexual liberation that the Pill offered Australian women parlayed into a social life driven by masculine exigency. Those women such as Jerrems who were concerned to "cut it" with credibility took on a masculinist swaggering libertinism. Some of the answers delivered in Jerrems' imagery should be subjected to the complexities of recent debates. No university lecturer and student could now exchange romantic poems, as did Jerrems with Paul Cox. Nor could a high school teacher ply favoured underage students with slabs of beer, and photograph the outcome.

The catalogue emphasises that Jerrems grew up in the Heidelberg area and felt bonded to the Warringal Parklands. In posing nude for male colleagues, she comfortably played up to the modernist gendered vision of the 'belle hysterique', the sexually expressive muse, reinforced by the old-fashioned bohemian vision of Paul Cox’s cinema; this latter link is freshly highlighted by 'Up Close'.

Jerrems’ admiring aestheticising of working class male bodies, outs artists such as Tom Roberts, William Dobell and Noel Counihan, who contemplated lithe male bodies in the guise of social commentary. 'Vale Street' is Norman Lindsay rendered in a post hippie modality; look at the glowing Pre-Raphaelite whiteness of the nude against the dark wry glances of the satyrs behind her. If the leering sharpies are the eternal working class larrikins on the make- give them a few million shareholders and they are Bondy, Skasey and the white shoe brigade. That pale white female presence reminds us of a vulnerable landmass which all too many see only in terms of what can be dug out, cut down, processed, killed, shipped off shore and sold.

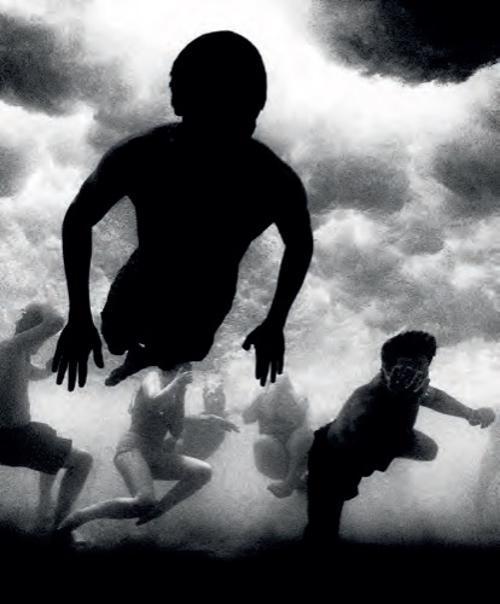

The most potent and memorable gesture of 'Up Close' was the perhaps unintended manner in which Jerrems’ self-conscious and peer-defined vision was outflanked by Nan Goldin’s rock and roll Bouguereau, her mesmerising and beautiful slide/music show 'The Ballad of Sexual Dependency'. The power, clarity and concentration of each saturated colour image is an unashamed celebration of subcultural mostly working class life and at the same time a reworking of art history in which all those submissive nudes and contemplated objects suddenly stride out of the frame and take charge of the representational process. The Buddha, so to speak, was within subject and photographer, and extended to the viewer who was assumed also to be capable of being a player, not simply an admiring courtier. Moreover Goldin speaks forthrightly where Jerrems prevaricated. Goldin’s money shots of urinating and masturbating youths are the phantom images that Jerrems never had the courage to bring into reality in her portrayal of the sharpie gang.

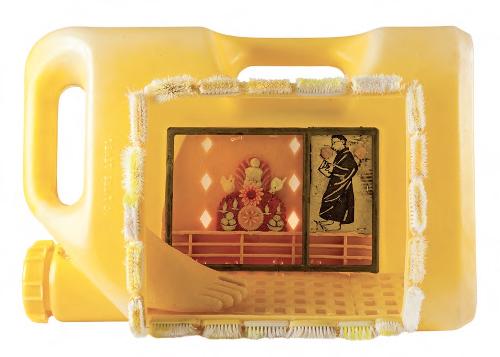

If I am being harsh to Jerrems, who is burdened rather than promoted by the vast mythologies around her, this does not undermine the manner in which 'Up Close' was fundamentally positive. The exhibition was presented with an intellectual thoroughness that is infrequently devoted to Australian women artists. Jerrems’ works were augmented with a range of vivid support documentation, including printed ephemera and moving image, to reproduce the embedded milieu, which was a catalyst to her working life.