Traveller: See! In the knotted bamboo grove (O terror and delight) a sudden

predatory gleam, the crouching tiger's eye.

Aschenbach: What is this urge that fills my tired heart, a thirst, a leaping, wild unrest, a deep desire!

(Quote from the libretto by Myfanwy Piper to Benjamin Britten’s opera Death in Venice based on the novella by Thomas Mann.)

Even from the time before you knew what a mother was, the primal question, 'what is my body good for?’ must have in some way taken shape. And will no doubt, at significant times in your life, be asked and answered again and again, ‘...an appendage, an offering, a temple, a sacrifice, a sewer, a wreck...?’ We can’t always consent to images of our body because, initially helpless and dependent on our proximity to others, identity remains bound to a brutal and desperate trade-off.

For this exhibition, the artists Andrew Harper, Mish Meijers/Tricky Walsh (aka Henri Papin), Caz Rodwell and Mat Ward were asked by the curator Victor Medrano to respond to the 'Little Red Riding Hood' fable, partly in answer to Catherine Orenstein’s book 'Little Red Riding Hood: sex, morality and the evolution of a fairy tale' and to David Slade’s film 'Hard Candy' which reverses the hunter/hunted roles within the story. 'Little Red Riding Hood', originally far more horrifying than the well-known Brothers’ Grimm version, has a history that could be seen to parallel aspects of an established psycho-sexual drama of primal drives followed by repression. The evil eye of folklore, the wolf/werewolf/grandmother in this case, demarcates a territory in which the body’s purpose is to devour/ be devoured. The first unrelenting expressionless eye prompts the innocent to ask, ‘is placating this unfathomable craving to be ravished, consumed?’

We can’t help being looked at and our consequent self-image is always ghosted by this look of the other. Medrano’s canny choice of artists allows for a compelling correspondence between the making of art and the traumatic primary formation of identity via this look. You could think that art itself is a shield protecting the artist from such a malevolent look, an excretion to throw the wolf off the scent.

Mat Ward’s black stencil wall painting I don’t wanna be saved is paradoxically reminiscent of eighteenth century silhouette portraits, taken from the shadow of the sitter’s profile. This technique, designed to render unique features, couldn’t be more different, a view of portrayal from the pop poster homogenising eye that he utilises.

Andrew Harper’s Re(a)d is a video performance of the artist’s lower face reading an older, more explicit version of Little Red Riding Hood. Below the monitor is a black T-shirt bearing a printed wolf’s head. Relishing the werewolf analogy, Harper’s performance, red wine (blood?) running from the corners of his mouth, reveals self-image as an other, a mask, projected to meet, control or mollify the supposed threat of a present incoming look. The tenor of this look is both an imaginary reflected projection from the self as other and the dimension of a look towards us we cannot locate. Being watched from an indeterminate place becomes a threat that has to be addressed.

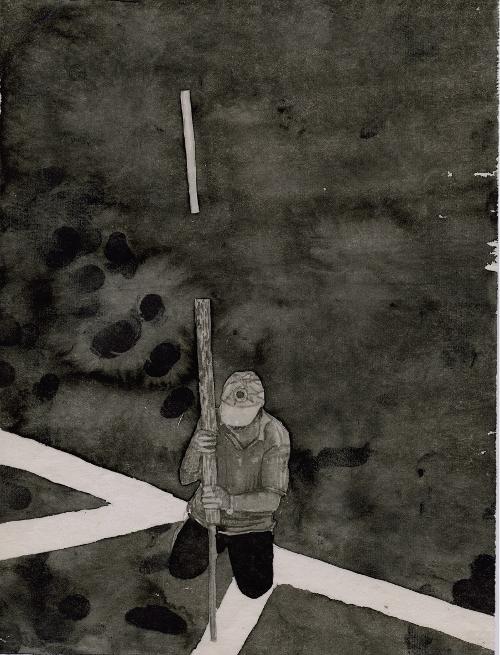

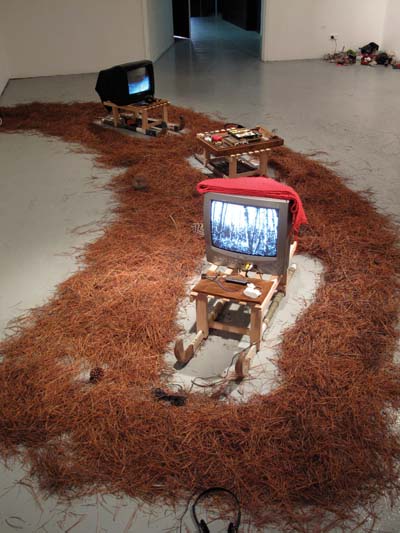

Caz Rodwell and Mish Meijers/Tricky Walsh (aka Henri Papin), both conjure up spaces where a shapeless desire searches for its object. Rodwell’s 'Not out of the Woods' and 'Turned Up Missing' evoke an abject ‘crime scene’, the ‘telltale ghost’ of an inconceivable event. Papin’s installation 'Boys will be Boys' comprises three sleds (‘The Watcher’, ‘The Prey’ and ‘The Hunter’) with hockey stick runners, upon which are two video monitors amongst various fetishistic collections of optometric objects, dolls etc. Both videos track the eye of the predator akin to the vampire’s movements in Francis Ford Coppola’s 'Dracula'.

Before civility had a name the nature of this threat called for desperate measures. To ward off being consumed by this wolfish eye, duplicity, trickery, even bloodshed might be demanded. For what does this stare ask of me and what does it see? What kind of object have I become for it? If only I could replace that object for another and slip away.

Art becomes this decoy, the offensive launched against unspeakable violation, deflecting the devouring unseen gaze in time to escape, turning the tables and making of you, the scrutinised, the invisible scrutiniser of desire - if only for an instant. Temporarily victorious, you can only wonder at the likeness between the image you made of yourself and the kind of image the wolf might have made of you.