Each of the books under review here is involved in telling Aboriginal art history and at its best this means not broad generalisations but localised information about places and people. Each book deals only with remote Aboriginal art, what Richard Bell calls Oogabooga art, art that is defined by its tribal origins and explained with reference to them. It is art that comes with maps and stories, songs and interpretations, rather than being flung onto a white wall or concrete floor and left to find its own way home.

Yet most of the books are concerned to emphasise that remote Aboriginal art is contemporary art not ethnography. They speak of it as entering the world story of art, such as it is, as relevant to contemporary life and to be part of the story of human creativity as more than a culturally specific practice. Yet surely as long as we call it Aboriginal art we are defining it ethnically and foregrounding its connection to a particular culture, separating it from other art and seeing it as a gift, a 'present' from another ethnography, one that is privileged to assert links back to a 'timeless' past which it brings into the present time for the benefit of all.

Isn't it rather the case that contemporary art has to change rather than that Aboriginal art should fit its Procrustean bed? Aboriginal art is a unique product of a culture with ancient roots. But is it contemporary art, and how and why does it matter whether it is or not?

Contemporary art can be seen as a genre embracing certain artists, certain galleries and certain markets. But it is also in many ways a loose category open to change and marks the end of isms in art. The house of art has many rooms. Is one of them called Aboriginal art or does Aboriginal art fit inside the room of contemporary art, stretching and altering it, making it new in a specific but hard to define way?

An ethnography is defined as the descriptive study of a socio-cultural system based on fieldwork; it is also a term that, like culture or anthropology, is often used outside a strict discipline-specific function thus it is possible to read about the culture of nursing, or to study the anthropology of the emotions and so on. Pacific contact historian Greg Dening who died in March 2008 wrote about the ethnography of his mind.

Aboriginal art is frequently said to have once been considered mere ethnography but to have now become contemporary art – a hierarchy jump something like what can happen to craft which sometimes makes a leap to the realm of art where a pot is no longer just a pot, where embroidery or weaving are seen as not just craft but as having strong conceptual dimensions. The measure of such leaps, apart from intellectual status and credibility, is the economic or financial value attached to them. Quite simply an art pot is worth a lot more than a craft pot, and contemporary art is worth more than ethnography. Maybe seeing all art as ethnographic makes more sense than cutting Aboriginal art adrift from its people and their culture. Perhaps seeing the present as something that doesn't only belong to historically dominant cultures is what is important.

The concept of the ethnographic present began with Stanislaw Malinowski and his fieldwork among the Trobriand Islanders, the Argonauts of the Western Pacific, from 1915 to 1918. Malinowski is said to be the first anthropologist to get 'off the verandah' and mingle with the objects of his study rather than sitting in an armchair in a study somewhere and extrapolating from other people's notes on life among different peoples. Yet the world of the 'Native' still tended to be written about as if it was frozen in a pure ethnographic present which preceded contact with the West and was presumed to extend back in a timeless, i.e. unchanging and unhistorical, way. This approach placed Western and 'Native' worlds in opposition, the West with its written history and the Native with its oral history, implicit also was the idea of the evolutionary movement of all human culture in a predictable way from 'prehistory' to history.

Today we are still often told that Aboriginal culture is the world's longest continuous culture and that its traditions have been going since time immemorial and thus it is 'timeless' which is to say unhistorical. Yet without history there can be no contemporaneity.

Can Aboriginal culture have its cake and eat it too? That is - be both very old and very contemporary. It seems so, and maybe there are important messages, of ecology, conservation, radicalism and conservatism, in the holding of this position, that the new is not necessarily the most valuable thing to be and indeed that the old can be seen to be new. Thus Judith Ryan writes of 'The Shock of the Ancient made New' and John Mawurndjul can say 'I always think of new things to paint&My work is changing. I have my own style.', and 'These designs are used all over Arnhem Land.' without contradiction. Yet I suspect if the contemporaneity and relevance of Aboriginal art is tested in a vox pop open forum by simply asking people in the street if they see Aboriginal art as relevant to them that most will say no but that it belongs, as it were, to another country that lies within this one. And that too is a contemporary thought.

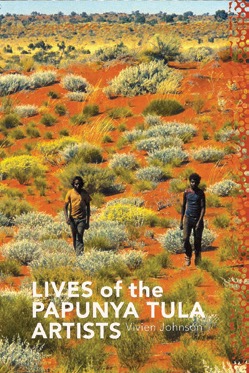

In the four hundred page 'Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists' Vivien Johnson has quite literally created a primary history document, by preparing genealogies and potted biographies of every Aboriginal person who has ever painted anything, even one small canvas, at Papunya since 1972. She has deliberately not focused on individual art stars and told me that as far as she is concerned the book is primarily for the artists, their sense of their own history and self-esteem; she is dedicating all her royalties from the book to go to the artists.

The book's title deliberately echoes Vasari's famous 'Lives of the Artists' written in the Renaissance, and considered to be the ideological foundation of all art historical writing; it includes artists such as Cimabue, Massacio, Giotto, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Titian. Johnson sees her subjects as equivalent to those great ancestors of Western art.

'Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists' is a great reference book and includes many fantastic paintings, some exceptional photographic portraits and some fascinating facts. Johnson's research really began, both involuntarily and voluntarily, on her first trip to Papunya in 1980 and has been intensively fact-checked over the last three years by Johnson and IAD Press staff. To me it is particularly important to see the photographic images of people and, dreaming upon them, to be enabled to see past their complicated names and stories in order to empathise with them as human beings, full of complexity and warmth. Early photos of some of the artists taken by researchers like Jeremy Long as far back as the early sixties are also included thus making this history one that goes back a lot further than the beginning of the painting movement and shows the immense transitions undergone in these artists' lifetimes from desert myall to world stage.

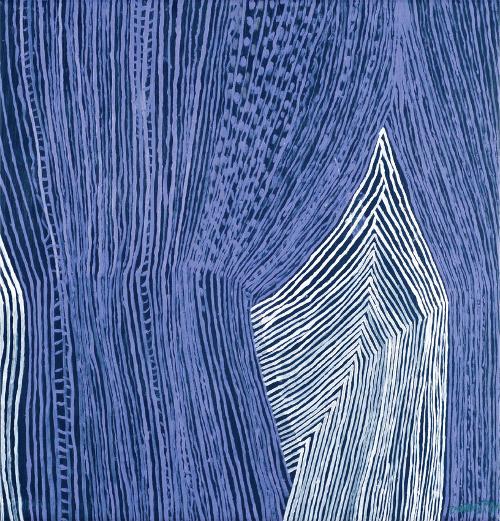

The almost equally massive 'Beyond Sacred: recent painting from Australia's remote Aboriginal communities : the collection of Colin and Elizabeth Laverty' has only a few photographs of people in it but it has many astonishing photographs of country most taken by Peter Eve, photos that make it clear that the country has fed into the art produced therein through its visions of correspondences and echoes, rhythms and patterns, ripples in sand, spinifex spotting the ground, striped hills, tree shadows and so on. The Aboriginal attachment to land has a strong spiritual dimension which involves seeing the land as living, the art draws on and reflects this vitality. But do we really need another big coloured picture book on remote Aboriginal art?

Well, this is actually a particularly superb picture book and among the written components of the book are many informative and enthusiastic pieces by art centre co-ordinators who have worked for many years with the artists as well as longer essays by Howard Morphy, Will Stubbs and Nick Waterlow; and a significant essay by Judith Ryan on shifts and developments in remote Aboriginal art from precision to looseness, from tiny detail to minimalism.

The title 'Beyond Sacred' is Colin Laverty's own understanding of the art as being religious and therefore charged with a certain power that is evident to those to whom its religiosity is inappropriate thus its appeal is 'beyond sacred'. Laverty's first art collecting guiding star was Abstract Expressionism and a Tony Tuckson in the collection appears on a page by itself near the front of the book. What is rarely noted is that much remote Aboriginal art, while it is not copying Abstract Expressionism, shares many of its goals and intentions, that is to put creation myths on canvas, to make an elemental art concerned with big things. The Abstract Expressionists all tried in their different ways to discover, find and invent those primal moments. The big difference is that remote Aboriginal artists do not need to use their imaginations to locate creation myths to paint. That the art sometimes ends up looking like Abstract Expressionism seems like a vindication of the goals of artists like Pollock, Newman and Rothko. So in its contemporary manifestations Aboriginal art does demonstrates a certain coming together, a reconciliation, of cultures.

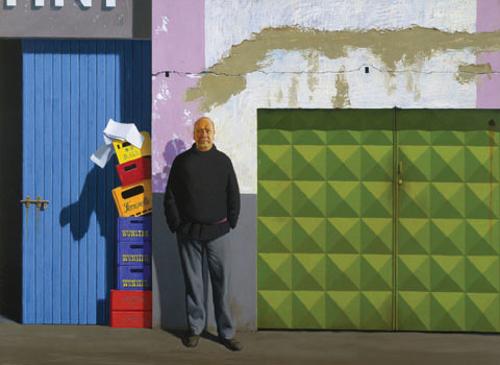

The Lavertys started collecting remote Aboriginal art in 1988 but it is only one part of their collection. In the photos of their house bits and piece of their entire collection are visible and I can't help thinking that mixing the two together in a book and letting readers see more of the juxtapositions that eventuate may have been a good idea. In other words aren't the Lavertys segregating their remote Aboriginal art collection as ethnographic by confining it to a book based on geography? Beyond Sacred is clearly aimed at a foreign market in containing a map and brief description of the 'Commonwealth of Australia' at the end. However it has no index so wanting to relocate something once seen in it can be a bit of a headache.

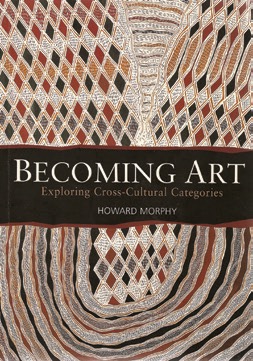

Similar in a way to Vivien Johnson's long relationship with Papunya artists, Howard Morphy has paid his dues in many years of research among the Yolgnu people of north-east Arnhem Land and has also been involved with publishing and thinking about contemporary Aboriginal art. As long ago as 1991 he co-curated, with David Elliott, an exhibition called 'In Place ( Out of Time) Contemporary Art in Australia' at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford in which he suggested that the category Aboriginal art includes 'in an ethnically-defined category works that would equally fit into that dominant unmarked category – contemporary fine art' thus challenging and changing the category of the contemporary.

'Becoming art: exploring cross-cultural categories' by Howard Morphy is about the history of Yolgnu art and the way that it has over many years moved into fine art markets and galleries and thus become recognised as fine art. This is how it has 'become art'. Morphy demonstrates that the same characteristic (aesthetic power) that make Yolgnu art valued in Western marketplaces are what make it valued in Yolgnu society.

Morphy wades fearlessly into art history and occasionally stereotypes Western art though his eventual aim is surely reconciliation and mutual respect. Calling Margaret Preston a South Australian artist and saying that her engagement with Aboriginal art has only been reconsidered and appreciated in 2005 both suggest some gaps in his understanding. Morphy is very impressed by Preston and uses a quote from her 'The ladder of art lies flat, art never improves only changes.' as the epigraph to his Preface. Only trouble is that the quote is stitched together from two different pieces of her writing, both admittedly written in 1927. The climax of Morphy's rich and thoughtful book is the cross-cultural discussion of Abelam painting from New Guinea with Narritjin Maymuru and his son Banapana in the ANU office of Anthony Forge, Morphy's Phd supervisor. It demonstrates that we all bring our cultures to the analysis of art and have to be ready to be wrong or to see things differently.

The mere title of Ben Gennochio's 'Dollar Dreaming: inside the Aboriginal art world' announces its interest in money and Aboriginal art. It is a sparely written, sometimes superficial, sometimes ingenuous, primer of the Aboriginal art industry. Using an interview format he covers a lot of ground in trying to understand the Byzantine complexity of its production, marketing and sale through conversations with the characters who are engaged in it from committed arts advisors stretching canvases and stretched to their capacity by the work (many are woman and they are all rake-thin) to the dealers sitting behind desks in the city who have other perspectives, and all the people in between.

The book spans some of Gennochio's time in Australia as an art critic as well as his more recent residence in New York where he writes on art for 'The New York Times'. It echoes similar works by Nicholas Rothwell and Bruce Chatwin about their journeys in the remote far north and outback. Yet Gennochio's journey is personal and contains a few epiphanies about Aboriginal art though it is worrying that he writes that the term Dreaming was coined by T.E.H. Strehlow when it was really Frank Gillen.

Vivien Johnson in her review of 'Dollar Dreaming' claimed that Gennochio does not get around to joining the dots (haha) in examining money issues about Aboriginal art, his ostensible topic. She wrote: 'His two main preoccupations: the scandals and the auction house boom that delivered the stellar prices in Aboriginal art are not unrelated phenomena but inextricably entangled. The power that Sotheby's and the other auction houses came to exercise over the Aboriginal art market was able to develop so quickly, so unexpectedly, and so dramatically precisely because of the disarray of the private dealers and the primary market brought about by the so-called 'Black Art Scandals'.'

Gennochio certainly does show that the industry is complicated beyond belief and that while corruption seems endemic many people are trying to fix it. As I write, the Draft of the Australian Indigenous Art Commercial Code of Conduct was released (on 18 December 2008) and has called for submissions before 20 March 2009.

Australian Aboriginal artists have successfully capitalised on their culture, their religion and their spirituality through art in a way that no other indigenous people in the world yet have or maybe ever will. Even though Aboriginal art history began a long time ago it is in a way just beginning and these four essential books attest to its richness and complexity. Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri's often quoted words 'the money belongs to the ancestors' is a profound statement in many ways as it acknowledges that spiritual power and wisdom remain valuable and can be sold though this does not disperse them. The gift is that Aboriginal art thus asserts the importance of cultural continuity and connection in all art.

Why art? Why Australia? It is the oldest country in the world, possibly the place where art was first made ever, maybe that is why there is so much art coming out of the remote areas, it is the land talking.