Despite its reputation as the most monumental and formal of all state galleries in Australia, in recent years the National Gallery of Victoria has presented contemporary art exhibitions with an intellectual rigour and respect for the audience that outpaces its often self-indulgent, selective and self-serving visions of heritage art; one thinks of the lost opportunity provided by the highly conventional Heidelberg School exhibition of 2007. The Rosalie Gascoigne survey follows the same high standards set by the recent Howard Arkley exhibition, presenting both a comprehensive selection of work and an authoritative catalogue that will be of great value to both scholars and practitioners, with high quality illustrations of the works in the show. The exhibition provides a point of reflection and analysis not only about the artist under discussion but also the society and the art milieu that nurtured and produced her. Gascoigne is one of the great achievers of the expanded Australian art consciousness of the 1970s, demonstrating that the strength and potential of Australian contemporary art can outlast its first moment of critical acclaim. The retrospective provided both intellectual and sensual delight. Gascoigne's reputation is confirmed with this retrospective, even though some of the work, for example 'But Mostly Air' (1993-1994), seems a little banal and empty, and the plywood landscapes such as the 'Age of Innocence' (1993) are contrived, heavy-handed and somewhat trivial. Some works based upon assemblages of natural objects e.g. the 'Feathered Chairs' (1978) and 'Feathered Fence' (1979) also border on the naff, and offer little of the insights and poetry of her best works.

Yet despite occasional lapses, Gascoigne's overall oeuvre remains impressive, singular and unchanging across the passage of years. Her works are as good as memory and illustrations suggest. Many have become iconic in any overview of the last three decades of Australian art, and yet when seen again their strength invites us to find something new, valid and unexpected in both the formalist rigour of their assemblage and arrangement and in the poetic suggestiveness and mobility of surface, recalling the transcendental nuance of Rothko's work and offering a validation of non-representational intellectualism as a fundamental value in art. Many are exquisitely balanced and thought through without any slippages or mistakes.

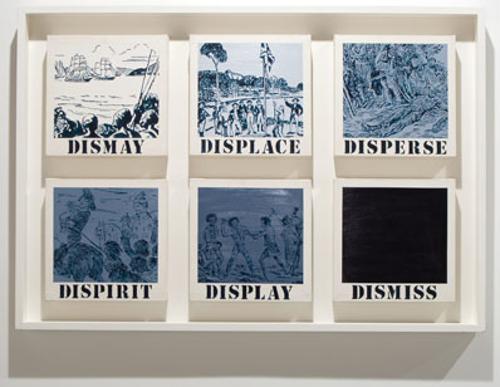

Gascoigne's sense of visual rhythm and pattern, as she slices, rotates and montages her found objects, produces a fertile range of images from the tight grids and legible poesie concrete of 'Promised Land' (1986) or 'Scrub Country' (1982) with their stencilled logos of vanished companies to the shimmering blurred asymetricality of 'Monaro' (1989). The artist plays confidently with a range of scales from the intimate to the monumental and with a range of intentions from the clarity of her early boxed works with their found imagery of postcards and prints and certain of her road sign works such as 'Street Lovers' (1990) to the enigmatic and fragmented such as 'Far View' (1990). Whilst her found domestic ware, shells, broken china and weathered glass are frequently used by other artist bricoleurs, Gascoigne's leverage of compelling visual content from the bourgeois chintz floral patterns of salvaged lino on one hand and the workaday no frills aesthetic of road repair signs on the other was an entirely idiosyncratic discovery which is one of the almost magic elements of her art. The transformations and subdivisions of her lino works are particularly effective.

Her works are timeless, but also recall a particular moment of expansion in Australian culture in the 1970s. Threading through Gascoigne's effective reconfiguration of the ordinary was the widespread interest in folkloric objects, the vernacular products and styles of settler Australia, informed by the pop art revisiting of the everyday object. Her early works particularly reference pop art, with their usage of scavenged Victoriana and art deco fragments. The seeking of beauty in the palimpsest, the worn, the weathered, partly allowed for a de facto narration in nominally abstract art, but also spoke of a scrutiny of the colours and character of the Australian landscape that could be tracked back to the Heidelberg artists or even to colonial art, insinuating the textures and materials of settler Australia into Australian nature as a sort of mystic marriage. The nationalist confidence of the Whitlam years was rarely expressed in such lyrical terms. Gascoigne also ennobles and romances a far less prosperous Australia where enamelled tinware did duty for cooking and hygiene, where commodities were packed in plywood crates, printed linoleum provided colour in interiors and houses were built of particle board that crumbled into cloud-like forms. Before post-colonialism Gascoigne could express the Whitlam era's straightforward love of country, at a time when the sentiments of the elite, at least of settler Australia, were not seen as an inauthentic, intrusive voice. Gascoigne found a parallel authority in post-war Australian poetry as well as visual art, across the spectrum from Judith Wright to Les Murray, who despite the difference in their respective politics also jointly presented a hypersensitivity and receptiveness to the landscape that outpaced the expected and conventional modalities of creative interpretation.

Curiously the catalogue, as did Gascoigne herself on occasion, seeks to distance her from the feminist movement, but it cannot be denied that she opened up a different placement of women artists. For three decades in Australian art, women artists in particular have found Gascoigne's authority and calmness, but concurrent romantic delight in rethinking basic materials, inspirational. Linda Nochlin posed the question in her 1971 essay of the same title 'why have there been no great women artists?'. In some ways I would suggest that Gascoigne answers the questions around the merit of women's art as memorably and with greater visual sensibility and formal strength than such international luminaries as Louise Bourgeois and Judy Chicago.