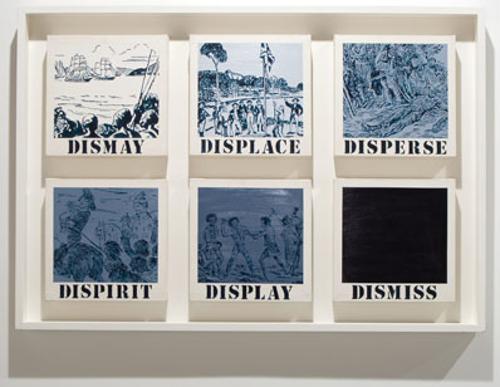

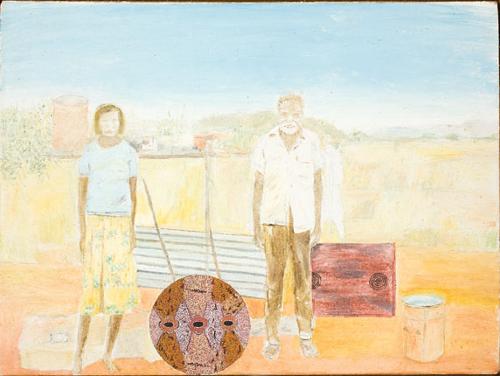

Ghost in the backyard

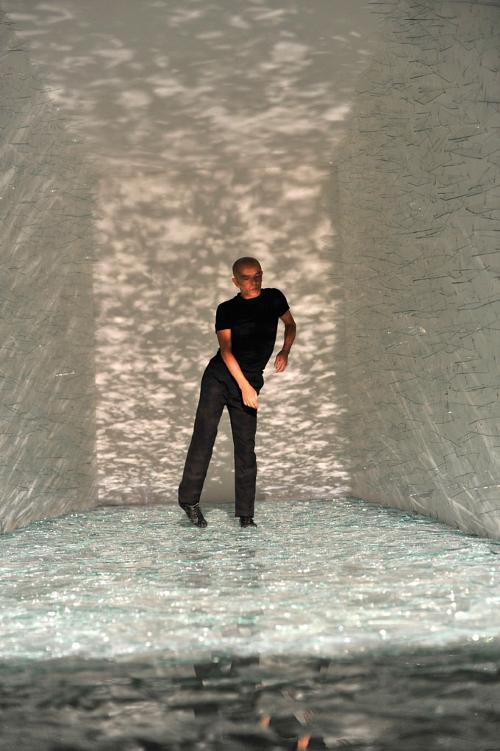

Using the work of two current Antipodean artists, Amy-Jo Jory and David Pledger, Melbourne-based Kate Sandford explores the place of suburbia in our consciousness and the way that even though real suburbia has changed, some representations of it have stayed the same.