Neil Haddon's solo exhibition 'Stranded' is filled with anti-portraits of lone beings in uncertain and abstracted space. The blacked-out silhouettes that appear throughout this body of paintings are larger than life-size, and their familiar poses might have been taken directly from snapshots or shadows, yet they lack identifying particularity. While Haddon's choice of both subject matter and materials – household enamel paint on aluminium – are characteristically mundane, the effect of their combination is calculated and disquieting. Shadows scorched against voids of unnaturally bright orange, pink and yellow evoke post-apocalyptic and even sci-fi scenarios.

'Abominable' is an image of endurance against unseen physical and/or psychological forces. A hunched man, depicted from knees up, shines ominously in gloss black. His posture is that of someone caught in action, his left arm hangs out from his body as though he is shifting weight and there is something confrontational and defiant about this stance. He is a monster – miserable, rejected, pathetic, possibly angry and dangerous. Before him stretches an ambiguous landscape, a patchy and vaguely grid-like texture of matt black worn away to reveal patches of pale yellow that can be imagined as forest, city or crowd.

Haddon constantly manipulates light across his surfaces through the juxtaposition of matt and high-gloss finish paint. For example, the technique of positioning matt black over gloss black (and vice versa) that is repeated throughout this body of work visually flips positive and negative space as the layers compete for primacy. Yet simultaneously, from other angles it is impossible to perceive a distinction between them. In this way layers of texture and imagery reveal and conceal themselves in paintings such as 'Young Man', where the pseudo-military silhouette of a male in hat and jacket sits behind a veil of cloud-like forms in dark glossy green. This topmost layer of the painting operates like camouflage print, interrupting form and outline so that the figure is obscured.

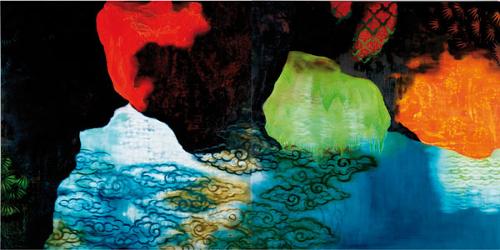

Though Haddon's palate is dominated by black, a limited range of garish colours accentuates these works. His combinations of tones - cream, eggshell blue and brown for example – banded in concentric rings to create globular forms over a number of the silhouettes possess 1970s associations. There is a resonance with the genre of psychedelic art here, and many of Haddon's scenes can certainly be interpreted as depictions of altered states of reality.

'Vestigial (40)', one of the show's larger works at 180cm by 160cm, depicts a full frontal male silhouette leaning back, arms by his side, legs apart, his head exploding into an inkblot-like blob. Orange, cream and yellow florets bloom behind his neck and shoulders like wings, or an Art Nouveau inspired vision of his aura. This could be someone on a dance floor, utterly absorbed in their headspace and sensations, frozen in the strobe light. The background is a distressed dark surface through which warm spots of light glow and, as with all these paintings, the lack of context and the stylisation of central subject manifests a sense of isolation, dislocation or at very least, introversion.

The figure has not featured highly in Haddon's practice to date yet all but one painting in 'Stranded' centres on a human protagonist. However, distortion and stylisation dehumanise these subjects, which are completely resistant to interrogation and therefore empathy. Nevertheless, despite the coolness of Haddon's aesthetic this work is an affective exploration of a subjective and inherently experiential phenomenon. The exhibition notes discuss 'purblindness', the partial loss of vision that results from moving from a space of low light into one of excessive light. These paintings are suspended, like remnant after-images burned onto the retina, in a transient zone of perception characterised by a lack of information. Like waiting for your eyes to adjust to the dark, experiencing these luscious paintings is to be stranded on the brink of realisation.