Ceramic figurines of cutesy dogs, ballerinas and maids–a-milking, normally conjure up visions of cluttered china cabinets in stuffy lounge rooms, infused with that indefinable smell particular to little old ladies. These delicate ornaments are both kitsch and deeply conservative. If they could vote, the National party would have a fighting chance. But Penny Byrne gives these right-wing figurines an extreme ideological make-over. Using skills from her day job as a museum ceramics conservator, she transforms them into audacious sculptures that tackle conservative politics, current affairs and social issues head on.

China figurines may be known for their feminine beauty and fragility, but most of Byrne's sculptural tableaux pack the powerful punch of a blunt instrument, coupled with the cutting edge of her razor sharp wit. They are like a swift, sharp slap to the face: heavy handed and straight to the point. However, Byrne's strongest pieces take a little longer to decipher. She seems to know that, used with flair, subtlety can be an even more effective weapon.

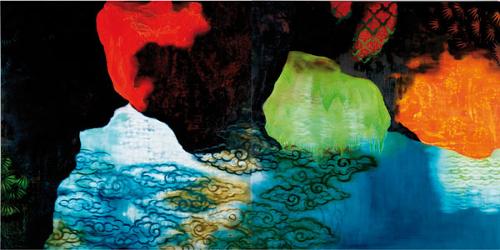

In 'H5N1 #3', Byrne has modified a bewigged ceramic lady so that she wears a shiny black gas mask and clutches a perky rooster. The original painted decoration on her dress is a variation of the blue and white Willow pattern, a classic example of Chinoiserie. Byrne's title and interventions clearly reference recent outbreaks of Asian bird flu, but this piece also neatly sums up a historically entrenched cultural love/hate relationship with Asia.

For centuries, the West has been more than happy to exploit and adopt the distinctive design elements of Asian cultures. More recently we have enthusiastically taken to their tasty cuisines, and are desperate to break into their massive, lucrative markets. Yet, despite our apparent openness to multiculturalism, we retain a deep undercurrent of mistrust. In Byrne's sculpture, as in society in general, the paranoia surrounding a potential Asian bird flu pandemic can be read as a metaphor for a deeply ingrained and ongoing xenophobia.

Here in Australia, echoes of nineteenth century fears of the yellow peril are reincarnated over and over again, from the officially sanctioned White Australia policy of the post-war years, to Pauline Hanson's Australia First party. And while the focus may have shifted in the early years of the twenty first century from Asia to Islam, John Howard's rigorous defence of our national borders against desperate refugees, his patriotic rhetoric, and proposed changes to citizenship requirements are part of this toxic legacy.

In fact, Howard and his policies have had a big impact on Byrne's work. The overt political agenda in her exhibition 'Blood Sweat and Fears' is a blatant and cheeky response to his anti-sedition laws. Our PM needs to brush up on his pop psychology; he should have known that telling an artist not to speak out was bound to have the opposite effect. And Byrne certainly doesn't shy away from the challenge. Her sculptures openly criticise the Howard government's stance on reconciliation, gay marriage, global warming and its blind acquiescence to aggressive American foreign policy, as well as its willingness to abandon Australian citizen David Hicks to the role of sacrificial lamb in George Dubya's fundamentalist 'War on Terror'.

But Byrne doesn't just point the finger at the powers that be. In 'Guantanamo Bay Souvenirs' she presents a collection of fey gents in breeches and hose, and china ladies in frilly dresses with the plunging necklines of the eighteenth century, painted the now ubiquitous orange of jumpsuits worn by American prison inmates. Byrne has created souvenirs for armchair tourists to covet and collect. They highlight the fact that the atrocities we witness seem distant and exotic. Shielded from harm by the screen of the TV, we watch horrors happening elsewhere. Safe at home, it is easy to believe that Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay and the whole mess in Iraq is someone else's problem. Penny Byrne's clever figurines are provocative symbols of our own complacency and complicity.