Over the years Primavera has evolved into one of the most eagerly awaited exhibitions on the national calendar. This is not because the artists are 'stars'. Even many art world insiders will not know all their names, let alone the impact of their work. Rather it is because this exhibition, funded to honour a life cut short, has become the launching pad for so many careers. Successive guest curators have tracked across the country, to artist run spaces, art schools and studios, and found the faces of the future.

In the past curators have shaped their selection around themes or worked hard to make the exhibition visually coherent. This has not been one of Aaron Seeto's concerns. He writes in the introduction that he wanted a 'survey bounded not by an artificial sense of connectedness'. Instead much of what we have here is a pastiche of ideas not fully formed.

Some of the most stylish pieces work best as elaborate jokes. Christian de Vietri's elegant elongated figures are separated in style and content, but only by degree. Here is a case of the execution being more profound than the idea. This is not true of Benjamin Armstrong's beautiful, elongated objects in glass and wax. They also are predicated on elaborate puns, but the visual and the conceptual do work in harmony - although I was sorely tempted to discover what would happen if another element – fire - was added to the delicately blown glass, the wax and the wood that looks like wick. The mixing of elements has another twist with Julia Deville's stuffed and bejeweled small animals. These are cute enough, but the whole process seems a bit laboured.

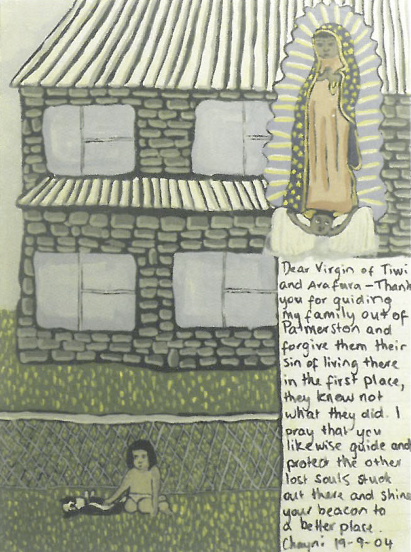

There is one point where the works act as a visual counterpoint to each other. Chayni Henry's rough as guts series of retablo paintings, where the potential elevated imagery of icons meet the realities of the underclass are one of the visual highpoints of the show. In scale they relate to Rob McHaffie's cute whimsical paintings that gently take the piss out of postmodern life. Seen by themselves McHaffie's little paintings aren't half bad. But because they hang in the room next to Henry's raw exposures of the black humour of the cultural outsider, they appear trite. This juxtaposition highlights a problem with the exhibition. Without an intellectual framework, hanging objects and artefacts together can work if there are strong aesthetic connections. But here there is no cultural connection.

All too often something that appears to have the potential to be profound disappears into a flippant joke. Peter McKay's Galaxy Project photographs appear to quote those photographic affirmations of the Sublime so beloved by astronomers, but then a foot imposed at the edge of the image warns the viewer that it is all an artificial construct with glitter. It is a good joke, but it does not have enough substance to justify its space on a main exhibiting wall in a major art museum. Other objects by the same photographer are simply twee. Their banality is brought into sharp focus by the wonderfully intelligent and exuberant paintings by David Griggs, which understandably have dominated all the promotional material. Griggs combines an understanding of the medium of paint with the complexity of cultural mix which is perhaps what Seeto was aiming for with the whole exhibition. A pity he could not sustain it. The worst of the lowlights by a country mile is Wilkins Hill's The Plague of Inheritance, which can best be described as 'bad drawings of Bart Simpson meet poorly conceptualised installation art'. It might have seemed a good idea at the time, but it is a pity this piece wasn't culled from the show.

It isn't an easy exercise to try to capture a moment in art, when all are young and there is more promise than achievement. The work of the best of these artists will change, transforming into something that will be hard to connect with this early striving. The rest will remain as a footnote to the art that was one curator's idea of the future in 2006.