1. The artworld has been doing forced stocktaking since the Treasurer and his servants at the Australian Tax Office started asking questions such as: are you in business or are you a hobbyist? do you make a profit from your work? It has been a humiliating time for artists, who have been used to thinking of what they do as a vocation rather than a business. Which is not to say that many artists are not aware of the various issues of an industrial kind that surround them, for example whether they get paid copyright fees or not. But being aware of and supporting campaigns to improve their lot does not necessarily translate into a full-blown attitude of obeisance to the bottom line. Most have other things on their mind when they are dreaming what to do next.

Almost all artists do not make a profit from their work. Some manage to break even each year on their costs, but often by having another source of income. A very small minority make more than the $50,000 p.a. which forces them to register for the GST. A smaller minority earn a very great deal of money from their art sales.

Internationally there has emerged recently a class of star artists who are in demand everywhere for Biennales and Triennales, and who employ lawyers, not gallerists, to manage and control their many engagements. In Australia those whose work belongs within the currently favoured boundaries of installation, digitally enhanced, or very obscure art, some of whom need magazines like Artlink to interpret and explain their meaning, are likely to have a better chance of being bought by national collections and winning big prizes. Others, like William Robinson, who sells very well at the moment to all kinds of collectors, may have chanced on a zeitgeist which is hugely to his advantage. Trouble with zeitgeists is that they can suddenly fade away.

Mid-career artists, especially male artists, used to be optimistic about their chances of recognition and reward. These days it is even more difficult than before to hold on to your niche. If you are an individualist who follows a personal course and are not attracted to the art world network you may find the going very tough indeed. Your gallery may do its best to promote you and yet the buyers are few and far between. This is a syndrome of a very large range of interacting forces which make it impossible to diagnose individual cases. The simple fact, which everybody knows, is that excellence and success do not necessarily go hand in hand. If artists are philosophical and maintain another source of income, they can continue to do what they believe they should be doing, secure in the knowledge that the work they do is not only important but valued.

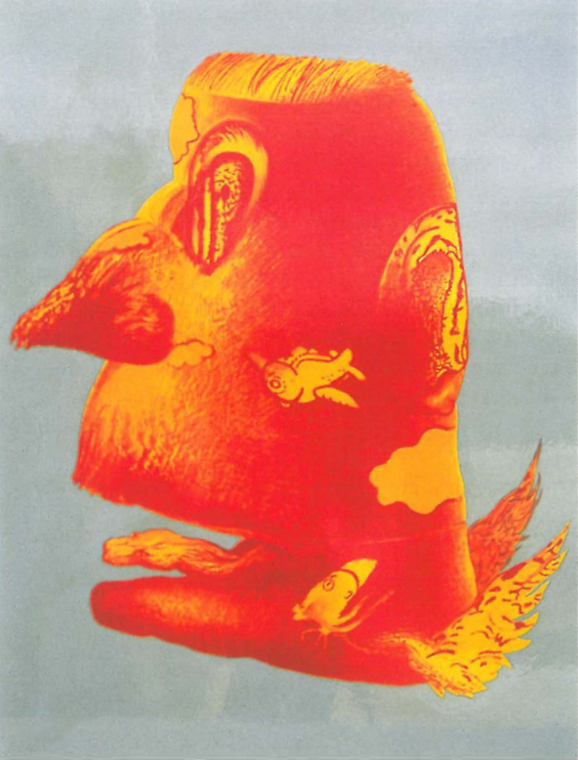

Four mid-career artists appear in this issue of Artlink - not a particularly unusual event for us. All of them are well-known and well respected in the art world and their work can be found in national and state collections. We are pleased to be able to bring readers up to date with what four committed individualists are doing: Victor Meertens, Asher Bilu, Frank Bauer and Jim Paterson.

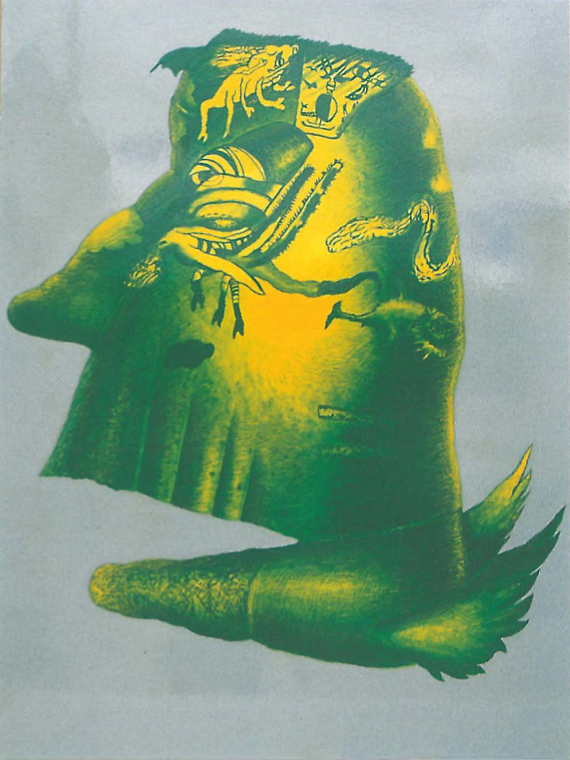

Works on these pages by Paterson are recent paintings, some of which have not yet been exhibited. Paterson is originally from Melbourne, now living and working in a huge former bakery in Broken Hill. Away from the distractions of Melbourne life he can be very productive and his output of canvases, boards and drawings is large. He turns his skill as draughtsman, designer and colourist to the creation of a population of forms, human and otherwise, which are frightening, pathetic and quirky at the same time. They morph from human to animal to vegetable; often they appear as from an unsettling dream. "Among Paterson's collection of oddities is Elephant Man, a glum-looking bare-footed man in a raincoat, who stumbles along, hands in pockets, with his enormous brain spilling out over his face."[1] Paterson's work does not lend itself to categorisation. His vision has elements in common with that of Peter Booth, but the range of his ideas is more inventive, more varied. Though the world he has invented is a fantasy, it is also familiar. We recognise the long faced cat-like man, the winged heads which fly across the canvas, the cars which are both people and weapons, the boats which tower up above us stacked with buildings and huge fingers, as things from our own world and not from an apocalyptic vision. They are paintings that talk of the weirdness of life but also make it human and manageable.

.png)

2. This issue provides another update - a tour around the country looking at new developments in public art, an area of phenomenal growth and seemingly more contested than ever. The position of artists at the bottom of the food chain in which the top feeders are the architects and managers is now beginning to shift, and some of the essays hint at the beginning of a coming of age of public art in Australia.

3. In response to the many requests we have had from those who missed it, we are publishing a version of the epoch-making public lecture Go Back! you are going the wrong way given by Donald Brook on the occasion of Artlink's 20th Anniversary in September. The capacity audience at Adelaide's Mercury Cinema to witness this one-man iconoclasm had the extra diversion of Brook's neo-biblical parables to illuminate the meaning of the most exhilarating philosophy many of us art groupies have heard for many years. Art museums and their ilk will never seem the same again.

Footnotes

- ^ Peter Timms, 'Variety spices Mora shows' Herald Sun, 18 July 1995