In an age where images are routinely cropped, airbrushed, retouched, scanned and re-imaged, photographic images which purport to reveal 'truth' are something that prompt immediate suspicion and warrant scrutiny. Editing images has always been an integral part of photography, with the limitations of lens and negative, and decisions by the photographer defining what will or will not be included in the frame, and what will suffice to document a certain event or situation. However, a semiotics of documentary photography has developed that uses specific devices to signify 'truth'. This documentary tradition, which has its origins in early photography, is best known through the work of contemporary German photographers belonging to the Düsseldorf school, the best known of whom are Berndt and Hiller Becher.

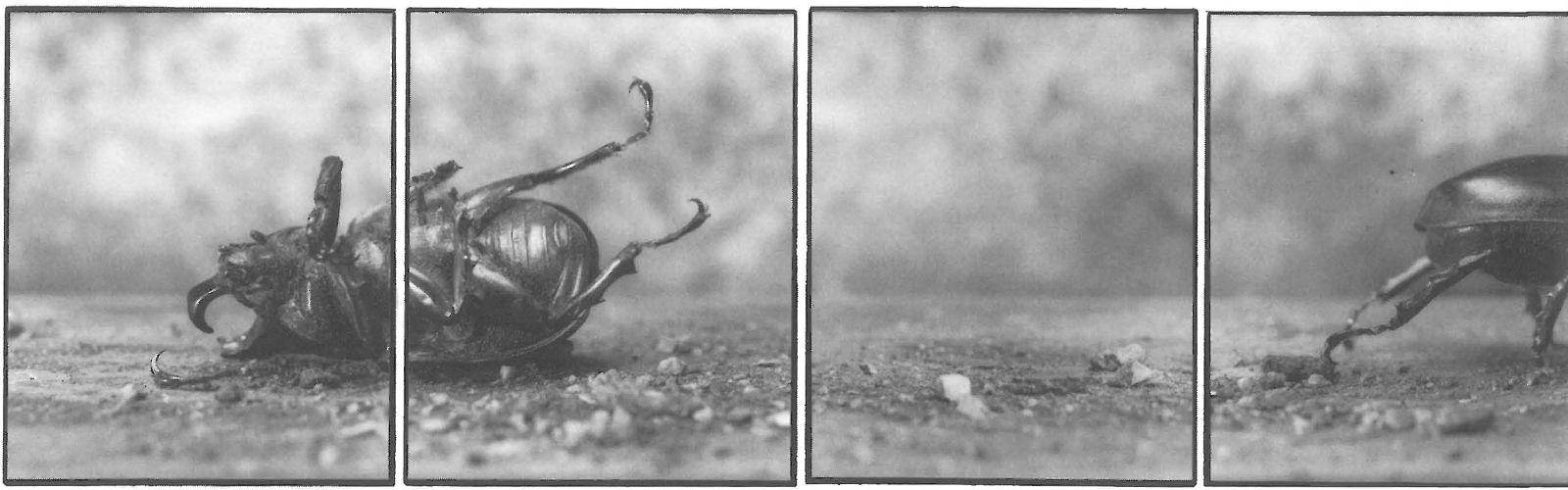

The Bechers' deadpan, resolutely black and white, sharply focussed fine print technique is also practised by Brisbane-based artist Joachim Froese, whose exhibition Rhopography questioned the validity of this technique to deliver the goods. Froese's photographs bore all the hallmarks of an event which actually happened, but one which was absolutely constructed, as theatrical as a Baroque still-life and as darkly humorous as a Samuel Beckett play. Froese created a world where disregarded, unimportant events or situations took centre stage and were writ larger than life. His series of multi-panelled photographs depicted the dehydrated corpses of various insects – moths, beetles, flies – in mock dramas reminiscent of miniature soap operas set on a dusty, dilapidated stage. The title, Rhopography, comes from the word rhopos, referring to the mundane or trivial things of daily life.

Each image comprised part of a series, from which a strange narrative could be deduced. With our own training in David Attenborough's insect documentaries from television, we may understand the life cycle and mobility of insects, but this direction was not taken in Rhopography. Froese presented us with a danse macabre, an allegorical tale that revealed the human traits of greed, lust and flirtatiousness in the midst of a slowly crumbling environment. One could follow, from left to right, or in reverse, a tale of withering relationships. This was a wickedly constructed, rather than revealing, look at the so-called natural world.

The action took place in an extremely narrow field of focus, creating a space not only grey and dusty, but claustrophobic as well. The insects, caught in this sliver of perfect focus, were revealed as gloriously textured, shiny and sensuous creatures. The viewer became slowly aware of the insects' imperfections - the holes and perforations in the shells, the fragmented skin, the detached legs – all pointed to the slow disintegration of this constructed world.

Despite the comically macabre subject matter, it was this gloriously decadent celebration of stilted life amidst death and debris that was curiously optimistic, and also full of pathos, for the human condition.

Froese continues to be influenced by detailed Dutch still-life paintings of vanitas in which bountiful flowers are depicted in their glory, but threatened by hungry insects, symbolising the ephemeral nature of life and the inevitability of death. Both the allegorical and visual aspects of this work are important to Froese, but have different meanings when translated into the photographic medium. For photography is not an interpretation or rendering mediated through an artist's hand, as there is always some trace, some vestigial registration of the 'real' object captured on paper. Whereas other artists can invent an insect on the canvas or screen, for the ardent documentary photographer, that insect must exist in reality.

It is important, therefore, that viewers be convinced that the images before them actually existed, in order for any fiction to be revealed as such. It is imperative that the code of documentary photography be adhered to, which it is to the extent that Froese does not crop or edit his negatives - what you see is what he also saw through the lens. This is not only a deliberate nod in the direction of historical painters who commented about life through their detailed allegorical paintings based on reality, but to contemporary media which manipulate documentary imagery to suggest a version of 'truth' which may never have occurred. His deliberate use of a non-digital medium questions the role that digital is taking – as it would be a far easier task to scan and manipulate images to achieve the same visual effect. But the photograph does not occupy the same space, its link to the 'truth', especially through the use of documentary photography, has become more critical in the face of increasingly manipulated images.