It is not often that one thinks of Judy Watson in terms of printmaking and art installation; or rather her talismanic paintings on un-stretched canvas are what more immediately come to mind. Opening in November 2005, The University Art Museum at the Mayne Centre of the University of Queensland quietly took the initiative of mounting a survey of this artist's imagery. What is distinctive about this exhibition is that it comprised mostly works on paper and that the six canvases included reinforced their authority and cohesiveness.

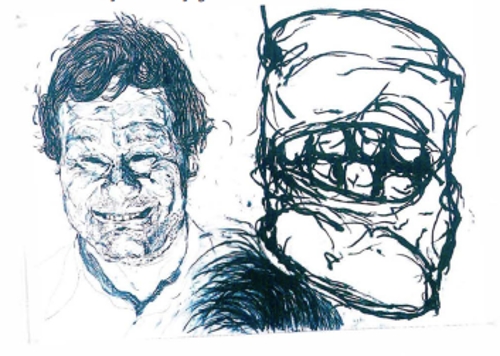

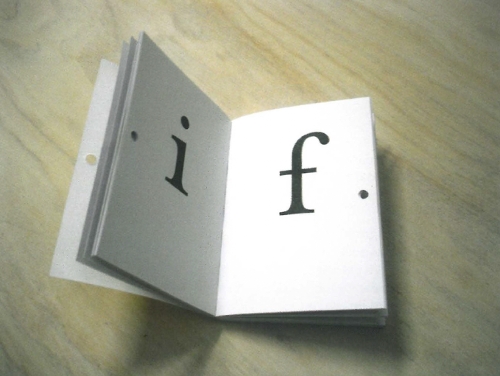

As a survey, viewers were able to trace Watson's development from the year she travelled to the country of her grandmother's birthplace in north-west Queensland to the present. This was a crucial decision as it is through her matrilineal heritage, the Waanyi people, that Watson has chiefly drawn inspiration. A small lithograph of 1990 titled the guardians gives an inkling of the potent connections Watson made with her Aboriginal heritage. The shadowy figures emerging from a shimmering background are like ancestors standing as witnesses in a dry and arid landscape. Through this and subsequent work the artist has paid respect and attention to these ancestors with imagery that is passionate, spiritual and restorative.

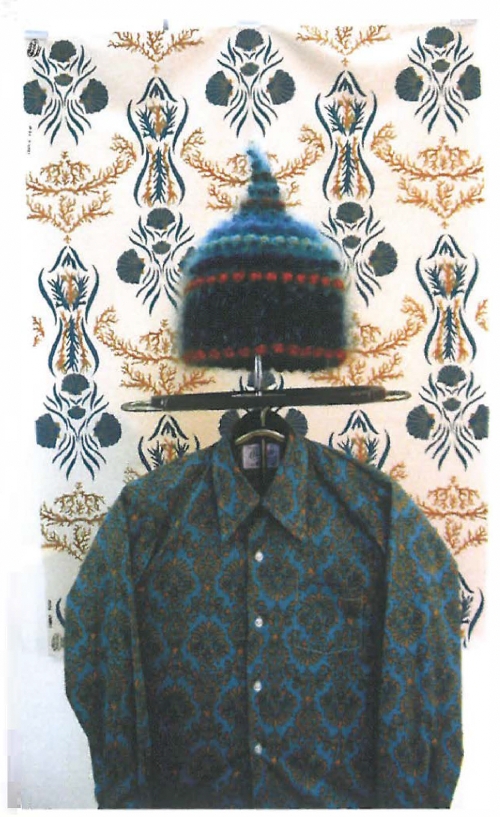

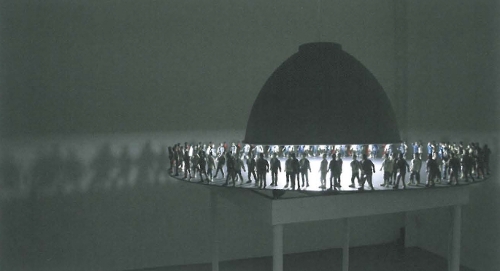

In the opening gallery, the stained canvases were grouped with their shield/head forms and intricate chalk marks hinting at traditional desert paintings and ritual body scarring. They are tactile maps of country and hides like those of animals (the wallaby for example). In her exhibition, Watson sought to remind her audience of non-urban landscape through the animal bones that punctuated the exhibition spaces in display cabinets and on the floor. Bones are potent. They remind us of our mortality, of time past, and generally have great symbolic power.

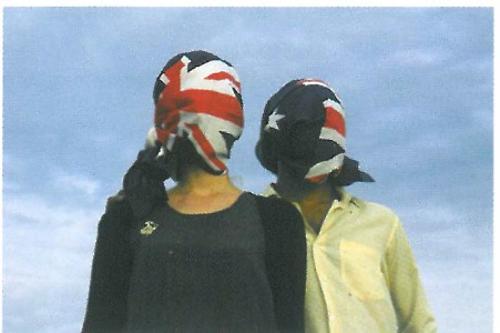

Watson not only expresses her identity as an Aboriginal person and as a woman but she is also fearless in taking a strong political stance. For example, the artist's recent portfolio of prints on display titled a preponderance of aboriginal blood (2005) drew on documents of not so long ago, such as the electoral enrolment statutes which classify whether a person is a full-blood Aborigine (and therefore not entitled to vote) or a so-called 'half-caste' (entitled to vote). Watson selected fragments of these official forms for duplication and in the printing process splashed them with blood-like ink. This meant that the didactic function of the portfolio is eloquent, yet muted; razor-sharp without posturing.

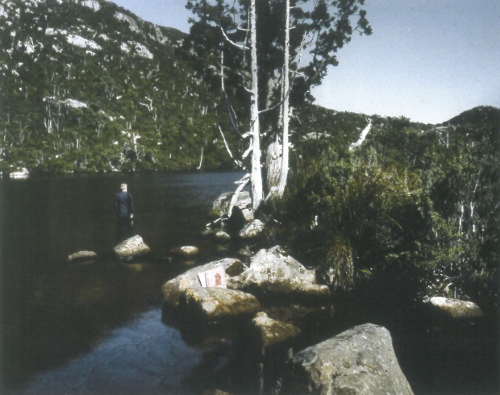

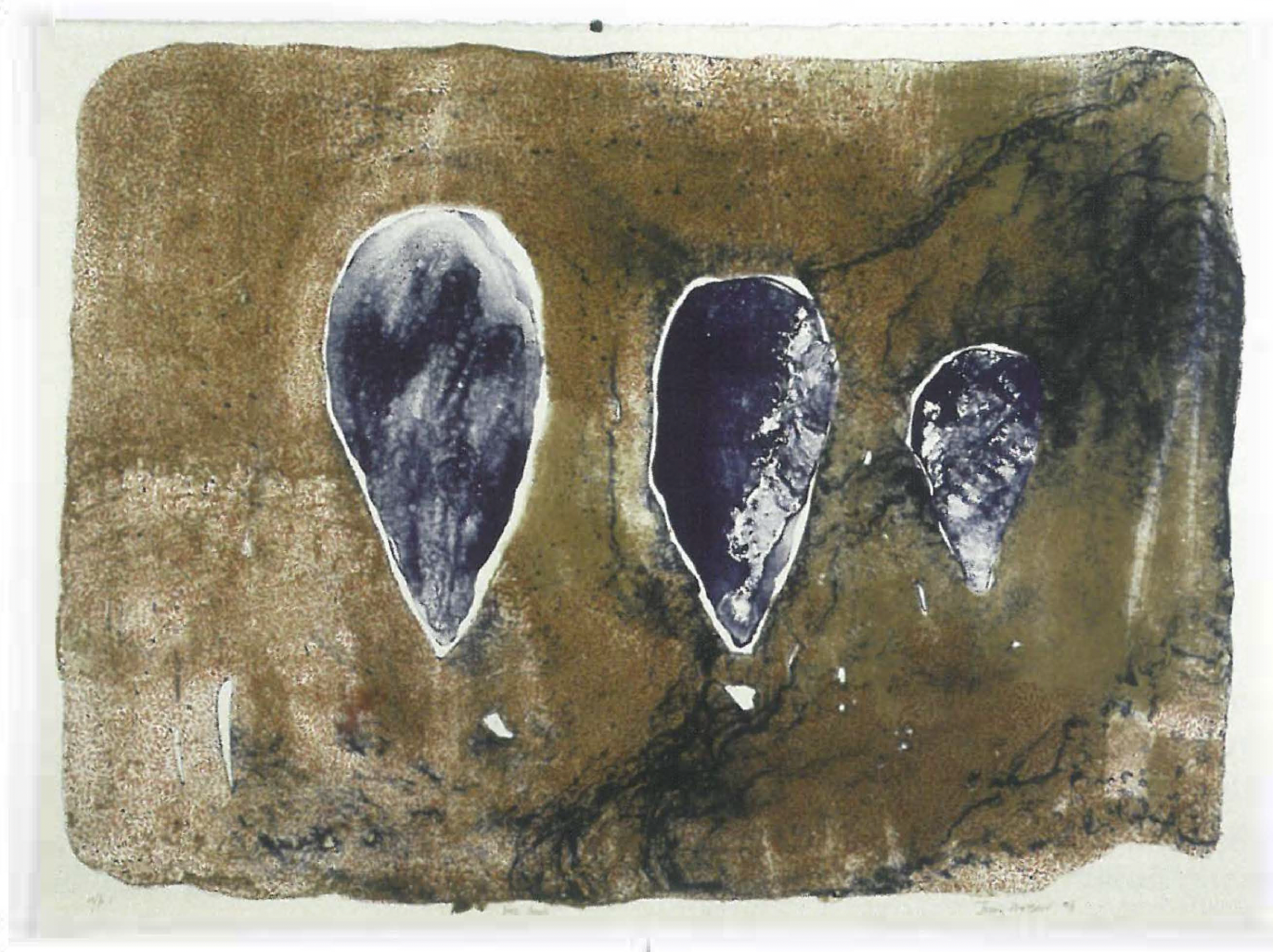

She is also an artist who conveys spiritual power across cultures and several of her works in the exhibition brought Buddhist references together with Aboriginal spirituality. The bell-like stupas in the painting big blue world with three stupas (2004), for instance, and the beautifully resonant lithograph blue pools of 1996 - surely a pun on the heroic Blue Poles by Pollock in Canberra? Watson produced the early prints herself until she realised that master printers (such as Martin King and Basil Hall) gave her more freedom to experiment and explore intricate processes. With King, she made lithographs using tusche for washes akin to the amorphous stains of her canvases and with Hall she was able to produce etchings bonded to the smooth surface of chine colle.

The physical reality of her textured canvases corresponds to a rock face and the chine colle, to the fineness of skin. With this exhibition, I was aware that Watson brings a ruggedness of natural terrain into the museum and a sensuousness of the body. But in acknowledging this context, she also asserts issues of how her indigenous ancestors have been traditionally categorised and collected (with anthropomorphic specimens and ceremonial objects). There were etchings with titles such as our hair in your collections (1997). Visual expressions of identity, of place, of country, of transformation and liberation were presented as a continuum in this important survey, however there was also an undercurrent of enquiry and vigilance.