If there is a time that is truly one's own it is while walking. Going from here to there relieves us of having to be anywhere in particular, allows us to meander with the thoughts that follow. It is into such wanderings that Strange Strolls intervenes. This audio walking project sends us away from the artspace and back onto the street with headphones and one of 14 recordings by artists from different parts of the world. They were often equipped with no more than maps and photographs of their site.

Swiss artist Dorothee von Rechenberg juxtaposes the bare Fremantle pavement with snow crunching underfoot, while Portuguese artists Maria Manuela Lopes and Paulo Bernardino overlay the Port's colonial facades with the sounds of an aircraft's interior. They ask us to give up our lonely mindscape for the companionship of another.

Sometimes the differences are brutal. Feminist geographer Begum Basdas complains about being harassed by men in a late night crowd. Other recordings play on the comfort of resemblance, as local Minaxi May invites us into the multi-tracked layers of her thoughts on a shopping tour, inflected with David Bowie and the tinkle of cash.

Important to the success of these recordings is the degree to which they resonate with the experience of walking the street. While the sound of boots in snow is novel, and atmospherics are merely pleasant, recordings of street sounds while already walking the street bring one back to the actuality of walking. A passing car may be in this city or in another, of this time or of the past. Turning to look for that screaming child, leaning back to see that low flying aircraft, is to doubt the relation between the ears and the mind.

In a doubled similitude of soundtrack and sound, the pedestrian body turns out to have a whole set of learned reactions that are quickly undone, in a moment-by-moment interrogation of the automatisms provoked by the pavement. As one turns to find that, yes, there is a truck bearing down on the body, that this truck is not on the recording, urban space becomes increasingly dangerous and uncanny, both familiar and unfamiliar.

When Viv Corringham asks us whether, as in her London neighbourhood, Fremantle is too being built and rebuilt, and the sounds of machines filter through the ears, it is easy to imagine the scaffolding, the web of destruction and reconstruction, lain all around. When she politely asks, 'Do you see what I see?' the answer often turns out to be yes, as a palm tree on a London traffic island conjures itself in downtown Fremantle. These juxtapositions are already there in the heterogeneity of a cityspace that shows off its globality, its palm trees and languages, reshaping itself by wish and whim.

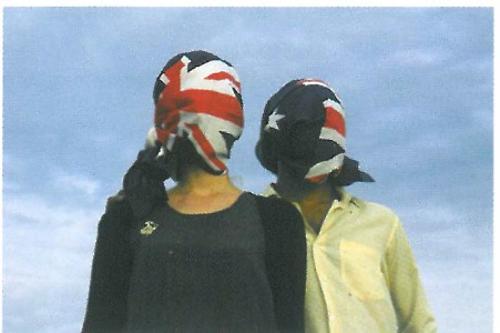

The defamiliarisation of walking turns out to be disorientating for a self that is used to navigating with all of its senses, and being safely ensconced in its own thoughts. It is this self-consciousness of walking, and of the solitude that it engenders, that marks out many of these pieces from the usual uses of the walkman that wants to overlay and shut out the world with music. The walkman more often encourages a wandering of thought than its interrogation.

In answering the solitude of the city with the intimacy of headphones many of these artists reach out, sometimes with song, at other times with confession, to offer a branch between places and times. For everyone else, however, this must look like another pedestrian to avoid. When a man asks Begum Badas, 'Are you playing the loneliness?' she answers, 'Yes, I am indeed playing the loneliness', before they go their separate ways.