Recently I sat down to read the lavish publication Interceptions: Art, Science and Land in Sunraysia which documents a series of collaborative interdisciplinary art projects, the products of an initiative developed over two years under the banner of SunRISE 21 Artists in Industry and the Mildura Arts Centre. This book, which holds within its covers an important sense of occasion for both Mildura and the Sunraysia region in general, has been ably edited by curator Helen Vivian and elegantly designed by David Bonsall. One gathers a sense that it may become a model for further artistic enterprises of this kind and that it has production values and a contextual-rich framework capable of having some critical purchase on the minds of metropolitan reading audiences in years to come.

Given that the project involved six artists, (Chris Booth, Craig Christie, Michael Doneman & Motoyuki Niwa, Megan Jones and Rodney Spooner) and an impressive mosaic of host organisations, including the CSIRO/Riverlink Consortium, the Murray-Darling Freshwater Research Centre, Lower Basin Laboratory, the First Mildura Irrigation Trust, the Salinity Management Consortium and the Horticultural Consortium, it is not surprising that Interceptions touts itself as "possibly the most ambitious Art project yet tackled in regional Australia".

It is important to note that SunRISE 21 is the anagram for Sunraysia's Regional Initiative for a Sustainable Economy in the 21st Century, and that its stated aim is to enhance the profitability and sustainability of irrigated agriculture by implementing projects to promote and facilitate beneficial change. This key to understanding one of the essential aims of the enterprise, given in Project Director Ian Ballantyne's Prologue, is unfortunately buried in the last pages of the book, along with sponsorship acknowledgments.

Interceptions is a valuable, if at times predictable, contribution to current interfaces being developed between art and science, the role of the arts in regional Australia, and how artists tackle a range of challenging environmental and cultural issues through their practice. Perhaps at no other time in their long association with contemporary art have Sunraysia and the Murray and Darling Rivers needed the collective voice of artists and cultural practitioners to be heard, even if to sing a eulogy or lament the loss of lagoons and billabongs.

As recently as January 2000 Senator Robert Hill (Federal Minister for the Environment) summarised the problems afflicting the Murray-Darling River System bluntly; "we have cleared too much land and we have extracted too much water from the river". Rarely has a Minister been so unequivocal about an issue, and his constituents been so unequivocal in their agreement with him. Accordingly, artists have important roles to play in the political processes now in hand regarding what must be done for the Murray-Darling basin.

One positive, if at times unsettling aspect of this book is that there is a chorus of different voices and different perspectives on offer. This democratic approach is perhaps neatly reflective of the kinds of vociferous debates and decision/non-decision making processes we have become accustomed to this last 150 years with regard to questions regarding the waters of the Murray River - so called riparian rights. And how timely that the publication is still relatively fresh off the press in this, our Centenary of Federation year, considering that the contest for and management of our water resources is as pressingly relevant now as it was to the mothers and fathers of the Federation one hundred years ago.

Chairman Lake's Foreword points out that the Interceptions project "is about using art to tell you about this landscape" - a kind of exclamatory statement that leaves one with a whiff of suspicion, perhaps an overreaction, that a public relations exercise is about to unfold. Who or what is doing the using, what is and isn't being told, and which landscape are we being informed about? Thus, much further into the fabric of the text we read: "The Trust saw it as a means by which it would receive widespread media coverage as well as promote Mildura/Sunraysia as the birthplace of large scale irrigation in Australia and assist in changing community views of the irrigation industry." It is perhaps not as well known as it should be that Renmark in South Australia was the birthplace of the first large scale irrigation colony to be developed in Australia, an agreement having been signed between the South Australian Government and the Chaffey brothers in February 1887.

Certainly Interceptions acts as a generous forum for writers as well as artists. Critics, journalists, scientists, and chief executive officers are all enabled to contextualise their various involvements in the enterprise and by so doing they articulate something about the complex political and social chemistry involved in the trafficking between art and science, land and community.

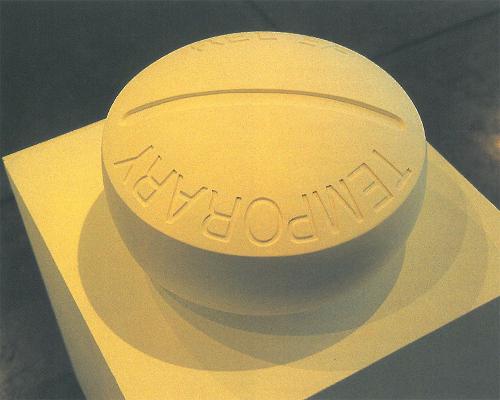

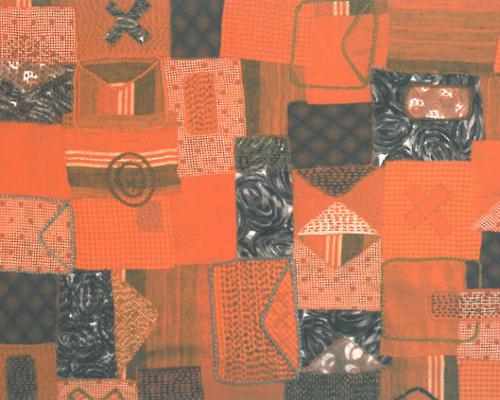

Despite the suggestion that positive and ongoing linkages have been fostered through the development of this project, this reader was left with a dizzying sense that there was a good deal of political opportunism being exercised by stakeholders in the project, no more clearly annunciated than in the manifesto-like account of the history of the First Mildura Irrigation Trust: "The threat of amalgamation to rationalise operation and management is always there and can be actioned at the whim of Government. The Trust [FMIT] must therefore remain competitive and have a strong grower support to resist any move of this nature." Putting aside any questioning of the merits of this proposition, it is sandwiched awkwardly between Tom Nicholson's and Kevin Murray's speculative commentaries and elaborations on Rodney Spooner's elegiac monument and Doneman/Niwa's works of opportunistic bricolage.

One of the insistent themes that runs through these pages is the tension between ecological sustainability and environmental disaster. As Mildura Arts Centre Director Ian Hamilton irritably notes in his Introduction, the term sustainable development, an oxymoron, is a term too glibly used, with the qualifying adjective perpetually subordinated. Indeed, the two words, in the context of the drama of epic proportions now unfolding across the Murray Darling Basin seem mutually exclusive terms.

In support of interdisciplinary efforts, Murray's essay succinctly sets the stage by quoting the Greek philosopher, Heraclitus. He quips that "the mixture that is not shaken soon stagnates" and that artists have an important and valuable role to play in facilitating an attitudinal change, enabling us to view things from a broader perspective. As he says, "we need a few of us [artists and scientists] to misbehave and so find alternative paths."

While this may be a commendable objective, few if any of these artworks illustrated conveys a sense of misbehaviour or the urgency of the issues at hand in our hinterlands. None have the eloquent simplicity nor the acerbic power of Bonita Ely's cry-in-the-wilderness Murray River Punch performance work conducted in Rundle Mall in 1980. (A mixture of cat's piss and mud in a solution of much gravity was on offer to shoppers and parliamentarians alike from a stall positioned within the pedestrian thoroughfare.) Nor have they the under-stated potency of the late John Davis' fugitive work Observatory, a soliloquy in sticks, made on the banks of the Murray in 1979 out of the local produce of eucalypts and mud. What we get instead is a kind of ersatz environ-mentality, monuments of permanence, and (god-help-us, let's hope not), memorials to contextualise our own cupidity and stupidity.

The authors lapse on occasion, given the absurdity of some of the following statements. A wild interpretation of artistic intention is posited for Earth, Water, People by Chris Booth (p.36): "The red sandy loam soil that forms the base of the sculpture provides a powerful message that this, together with the water nearby, is the basis for irrigated crop production." We are also informed, erroneously, that the cairns of stones used in the construction of Booth's 'earth blanket', echo the use of similar arrangements of stone by traditional Aboriginal people in the area, "marking graves and dreams" (p.31). Such was not the case; both written and visual records show the use by Aboriginal people of tree limbs and sheets of bark bound by a lattice of fishing nets to keep all in place.

Exasperatingly we are told by a triumvirate of writers (p.45) that "the river system, now regulated by four major water storages, sixteen weirs and 5 barrages have ensured a continuous supply of fresh water [which] has reduced and stabilised the salt levels in the Murray, which in the river's natural state fluctuated widely." Conclusion: man's intervention has improved the riverine environment!?

Similarly it is glibly announced (p.64) that "the land is now more productive than at any other time since irrigation commenced [attesting] to the use of sustainable practices and the long time viability and future of irrigation in Sunraysia". Meaning what - that increased productivity is a reliable barometer of sustainable land usage?

The bludgeon came for this reader when Henry Tankard (Chairman - SunRISE 21) pointed out that the "Sunraysia accounts for 30% of the nation's vintage, [has] some of the largest wineries in the Southern Hemisphere [which] are expanding their facilities to cater for a huge increase in the planted area." Such alarming statistics should worry the concerned citizen, particularly as we were all recently witness to the South Australian Government's announcement that more Murray water is destined to be piped to the thirsty Barossa Valley to service the wine production boom in that region. We were all listening, weren't we?

It is incumbent on all citizens to get involved, become informed, and to think more carefully about the purposes to which water is put, and realise that it will involve difficult decisions and choices within our lifetimes. While it is necessary to support efforts of governments and communities in their ongoing efforts to manage and contain the environmental problems that we have created, it is also imperative to be vigilant, and if possible not become despairing when confronted by the deep contradictions of western cultural and economic imperatives.

It is also necessary to keep an open and yet critical mind about what the role and value of art can be in all of this. It is vitally important that artists and scientists do not become the handmaidens of industry, or part of the easy vocabulary of spin-doctors. As artist Malcolm McKinnon pragmatically notes regarding the photographic series Sites of Interception by Megan Jones (p.41), "salinity affects the daily lives of many people living in Sunraysia - it's not somebody else's problem, to be rectified by a distant, benevolent agency".

Pertinent to this recognition may be the challenging observation made by Dr Stuart Hill, (who spoke lucidly and entertainingly at the Mildura Palimpsest Science/Art Symposium last year), that "it is important to distinguish between 'deep' sustainable change, which usually requires fundamental redesign of the systems involved, and of our relationships with them, and 'shallow' adaptive, substitutive and compensatory change, which usually unintentionally protects and perpetuates the very structures and processes that are the sources of the problems we are endeavouring to solve".

In conclusion, one dares to suggest that this interception between art and science has the flavour of being a dangerous liaison as much as a fruitful collaboration, a tradeoff between instrumentality and interpretation, and perhaps a poetic reminder of Helen Vivian's remark, sotto voce, that "our knowledge of this place is shallow." If Interceptions achieves nothing more than to foster a greater awareness, debate and understanding about the need for balance between the preservation and restitution of the natural environment against the demands of development then it will deserve a resounding endorsement but I'd rather be years in the judging of its efficacy, notwithstanding all of the efforts of the Save the Murray campaign run by The Advertiser throughout 1999-2000. Aptly opening his buoyant review of the 1978 Mildura Sculpture Triennial, David Dolan Advertiser art critic at the time, quoted the City of Mildura's motto; perhaps it is more relevant to close with it here: - "Ye shall know them by their fruits." Matthew 7, 16.