In many ways Queenstown on Tasmania's West Coast is like a lot of towns around Australia, caught as it is in the general stresses which all remote and regional communities face. Queenstown is a mining town and its troubles are those peculiar to mining towns. Tough, hard country, single stream economy and the whole community hostage to vagaries in the price of metals and the knowledge that, at some time, inevitably, the mine must close. The residents of this unique and strangely beautiful place are strong, resilient people.

They have faced not one major mine closure but three - each touted as the end. Queenstown is reinventing itself, building a new economic base and imagining a new identity. This is no simple thing. Mining defines a place and its people in specific and powerful ways. It is hard to imagine a new consciousness for a place so steeped in its rich traditions and history or a community more welded by adversity. And in Queenstown there is no escaping the towering landscape, everywhere showing the traces of generations of human toil. This modification of the landscape is on the epic scale. The huge open cut mine behind the town is slowly sinking as it collapses into the deep drives below, like a mirror of the mountain which once stood above.

People like artist Martin Walch and writer and Unions Tasmania Arts Officer Richard Bladel are drawn to the west. Whether the initial attraction is the extraordinary landscape and the magnetic fascination of the mine or whether it is the complex and fascinating history and unique and resilient community, the west coast gets into your bones and doesn't leave you. In his own practice as a writer and playwright, Bladel, (who conceived and developed the project), has always shown a concern for social issues, and the dynamics of family and community.

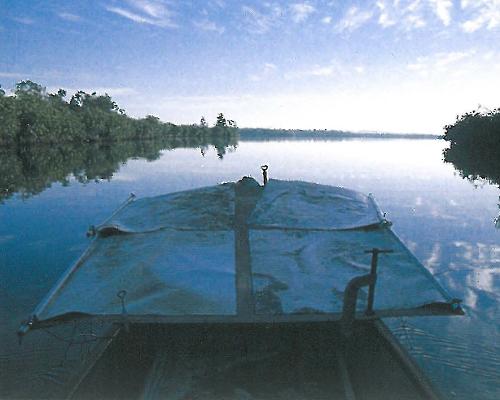

Few artists could be better equipped than Martin Walch to undertake an arts project such as Mining the Imagination. Walch has a long association with the west coast, initially through acting as a guide to the Tasmanian University's Centre for the Arts Wilderness Research Program and later through two self-initiated arts projects working with the Mt Lyell Mine. Through this Walch has built close and trusted relationships with the community of the Coast as well as the mine management. In mining towns this is often a divide which places people clearly on one side or the other but Walch straddles it comfortably. When he uses the term 'Wilderness', he applies it in its archaic sense as freely as in its current usage. In this context the term refers to the fact that a place is, for whatever reason, uninhabitable and one of those reasons may well be that humans have created that place through their activity. The construction and deconstruction of the landscape is a particular fascination Walch brings to this and other projects. His apprehension of the ethical environmental implication of mining activity does not disallow a deep awe and appreciation of the resultant structural modification to the landscape and even the remnant hulks of machinery and workings, slowly returning to the land. This character of ambivalence is highly attenuated in this context. Locals share with Walch a strange mixture of awe, affection and frustration with this place.

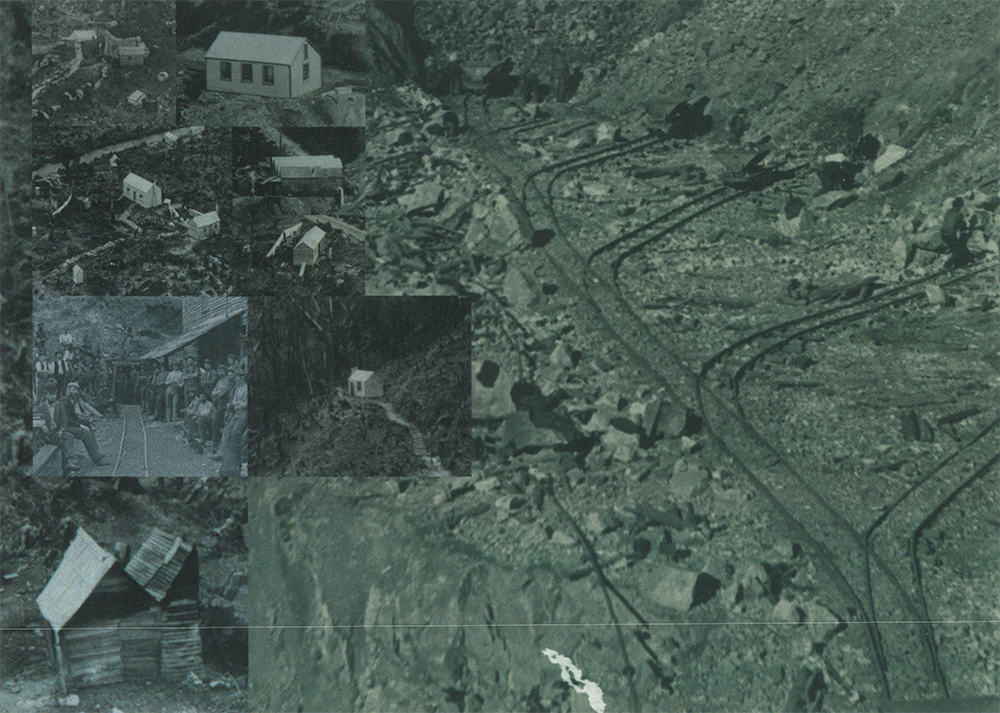

He uses a digital collaging technique to draw together historical images, images provided by the community as well as his own in a seamless amalgam which reflects the complex overlay of experience and collisions in time typical of the coast.

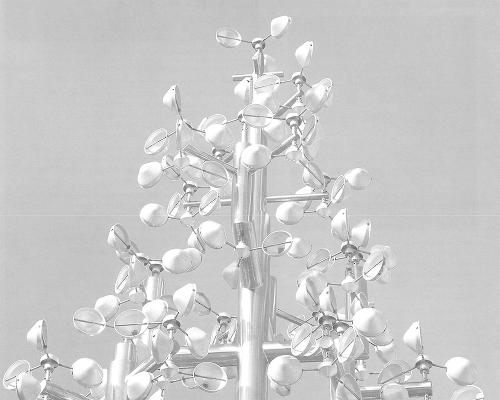

Bladel was aware that an investigation of the mythologising and romanticising of the coast and its lives was overdue and this expansive project does just that. A writing project How wild is your West, enabled local community members to put a personal case. Numerous photographs, drawings, models and some installation components made this a huge and diverse show, with all the attendant variations in artistic experience one might expect. The time-frame for development was punishing and success depended on the dedicated involvement of artists like local photographer Rick Eaves. Sound artist Poonkhin Khut worked with samples of conversations from a diverse range of people and these were discreetly woven into an aural background and second level of information for the show.

Community consultation not only formed the basis of a relevant project but also proved that the concept was not one being simply foisted on the community from the outside. Bladel explained that if the project designers and participants had got this wrong in Queenstown, quite simply, no-one would turn up. The idea that this was a project which could initiate further projects is a key premise on which it was founded.

The site for the exhibition was the old Mine Management office. One local miner confided to me that in his whole working life the opening of the show was the first time that he had crossed that threshold. It was therefore amusing to note, under the portico at the entrance to the building, wry touches like the washing line installation developed by Leisa Tyler and a group of Queenstown women, making reference to the Queenstown tradition of hanging washing under the verandah due to the enormous rainfall in the region, neatly foregrounding the role of women whilst thumbing the nose at the centre of power and prestige.

If community engagement with art and artists can be effective it is through dialogue and that was evident up to and beyond the crowded opening. The balance of talented (and sensitive) professional artists with people who have a story to tell can produce great results. And there is something almost beyond description about the experience of hearing a brass band in an enclosed space with a stubby in hand ...