In his catalogue essay, Alan Cruickshank, the curator of Remove, ruminates on what he calls "...a pervading sense of ...alienation and expiration in contemporary art...", Now there's no doubt that there's something like that in the wind, but hasn't that always been the case? Putting issues millennial aside, is this alleged malaise evident 'in' the work of artists, or does it emanate from the cultural context in which artists work? Is it because artists (that is to say, those artists who seek creative autonomy) are being disenfranchised in the expanding context of commodity culture? Is it because as a consequence of the new media revolution art-like experiences are increasingly accessible? Is it because what we've known as 'the art world' is becoming increasingly invisible?

While the curatorial intention is not specific in these matters, the curator has succeeded in gathering together a body of work that is riddled with the semiotics of displacement and work that camouflages itself under the riddles of its own disappearance.

There is, however, little angst evident on the visages of the two men in Shaun Kirby's Philosophy: The Basics. One man is drinking deeply and holding a bottle, the other leers drunkenly at the camera. The images have a documentary look - mug shots from the files of the Temperance Society, perhaps. These images are mounted on 'placards' and between them is a third 'placard' on which is scrawled, "different people deserve different amounts". In a typically Kirbyesque 'remove', this text doesn't refer specifically to the drinking men and it originates from a philosophy primer. The 'placards' make ironic reference to a perceived failure of avant-garde agendas in the current age of economic rationalism and collapsing grand narratives - an increasingly popular view, of which this artist is deeply suspicious.

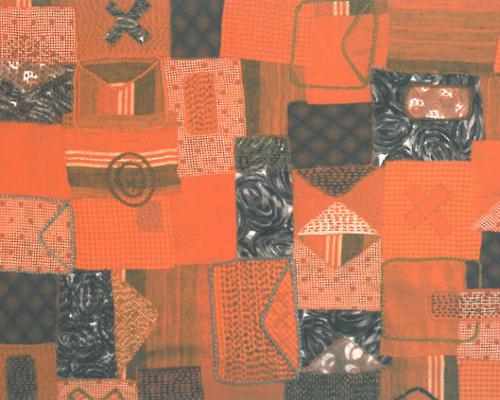

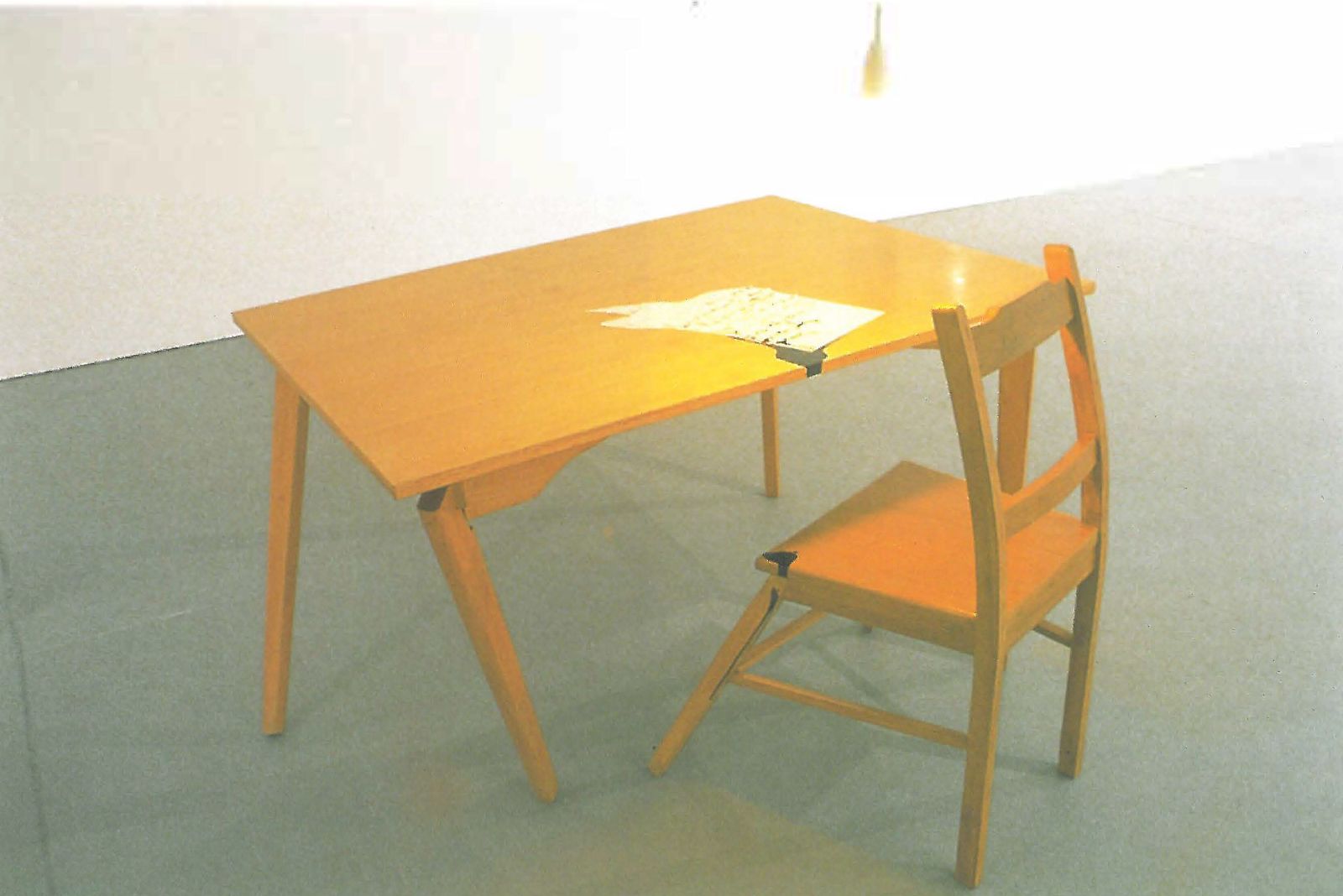

Kirby's wry commentary on the veracity of postmodern ennui finds an ally of sorts in Sally-Ann Rowland's darkly playful commentary on the vicissitudes of love and art. Love-letter 2000 is art about writing about love. The work is also suffused with other elements pointing to interrogation and torture, creativity and confession, isolation, despair and abandonment. The ubiquity and decrepit state of the table and the chair as the basic furniture of the writer's art reads as an ironic cliché on the condition of the creative psyche in a post-narrative age. The 'letter', painterly and expressionistic, isn't going anywhere; it 'melts' on the table dripping off onto the chair. And yet the solitary light globe is also evocative of an idea, an inspiration.

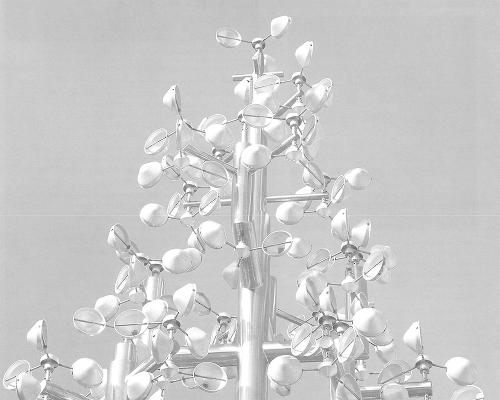

The photography in this show was interesting at a number of levels. Of the five artists involved, two showed work that is exclusively photographic although poles apart in conception and presentation. Jacky Redgate's Life of the System is a series of highly crafted life-size, C type images of some highly crafted antique objects set starkly against matte black grounds and framed as exotic specimens, veritable cabinets of curiosities, their immaculate presence consuming the gaze. It is as if these images appear to defy the notion that only new media has verisimilitude in the increasingly flattened space of reality between the image and the thing imaged.

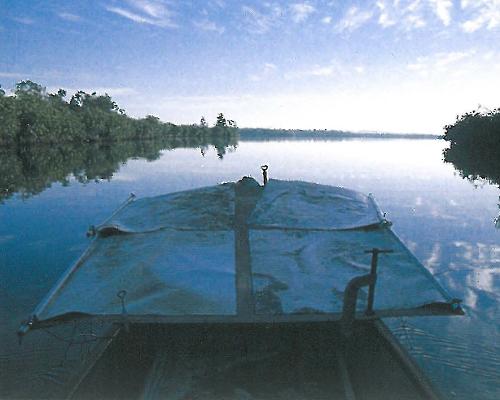

At the other extreme of the photographic method is the series of images Still Life in the Australian landscape, the aesthetic content of which is set at craft-level zero. Hope Lovelock Deane handed out disposable cameras to a bunch of people, some artists, some not, with the instructions to seek out and record a still-life in the landscape. The resultant images are shown as slides projected onto a stretched raw canvas, the inclusion of which extrapolates on the relativities of texture and authorship.

The artist as mini curator is an interesting conceit in its reference to systems within systems of representation. In this context the non- artists became artists and their work is indistinguishable from that of the artists, bringing into play ruminations on the nature of art and the role of the artist that are as old as the 20th Century and as recent as the current debate as to what constitutes public art in the age of spectacle.

Derek Kreckler toys with an arcane notion of spectacle in his installation BlindNed in which looped 'footage', that looks as though it was made at the birth of cinema, depicts a blind Ned Kelly, his white stick totally ineffectual in the scrub, tentatively moving forward, only to suddenly vanish and then reappear at the beginning of the loop. The installation also comprises a tableau of a couple of stuffed mammals, a kangaroo and a wombat. The use of these absurdly 'authentic' props, along with the counterfeit look of the DVD loop and muted lighting, combine to create a surrealistic mytho-poetic twilight, an antipodean Gotterdammerung of simulacra and repetition.