For some people Tree Stories is the kind of book that must be devoured at one sitting. It is not a long book, in that it is made up of short stories and has large pictures, but that is not the reason for the inclination to read it immediately regardless of what else one should be doing. For people who feel strongly about trees this book feels as though it has been written especially for them, revealing as it does the sentiments of real people in cities, towns and in the country who feel the same way as they do.

This is no objective study of botanical history, or of the biogeography of plants, it does not track the debates over exotic or indigenous, nor does it give statistics of dieback or deforestation. It comes at trees from the perspective of the people who love them, not necessarily those who would go so far as to say they love trees in general, but those to whom a particular tree has meant something. The reasons for this aspect of human behaviour are defined variously by describing the effects that trees, especially large trees, can exert on us, their stillness, silence, strength, their apparently benign attitudes to what happens in the shade of their leaves and branches.

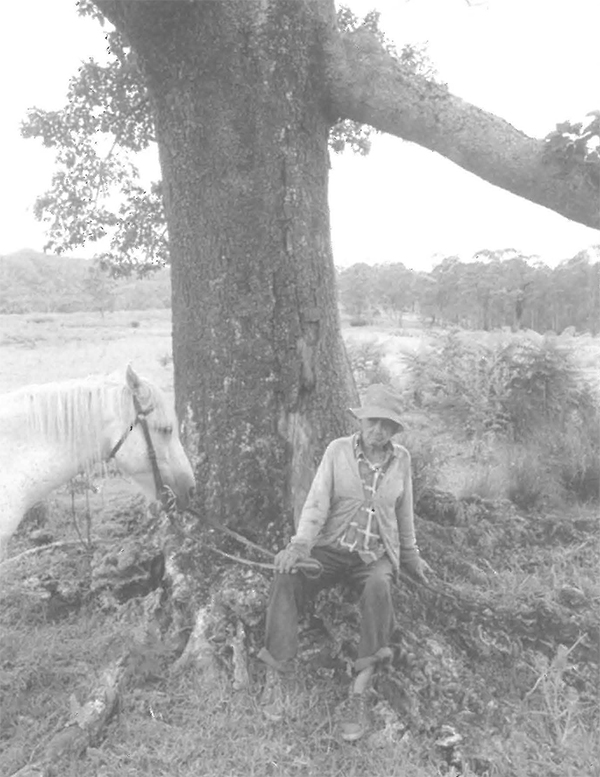

When Peter Solness, a photojournalist, first decided to make a book on this subject he had already spent 20 years travelling around Australia, South East Asia, South America and Melanesia. He started on a motorbike with a kitbag full of film, recording the outback from coast to coast, getting to know what made people tick in small communities. He has lived in cities, Sydney in particular, and seen its suburbs and its surrounds change over the years, as development encroached on open space. With the photographs he has documented whole generations of places and their people but it was in the mid-nineties that as a result of seeing a Four Corners program on industrial logging in Papua New Guinea that he came to the idea of telling the story of people and 'their' trees. On the spot in PNG he realised that the loss of the trees to the villagers was creating a deep wound in the culture.

"In the wake of the Melanesian experience I began to look at the way we portray our own trees in the Australian media. The Melanesian project also reminded me of the 'campassion fatigue' many people now feel about bleak issues such as environmental destruction in third world countries. I began to wonder if there was a more positive way to raise awareness towards trees in Australia."

Having decided on this, he found he already had the nucleus of this collection and then set out to go back to the trees he knew about and record interviews with those who regard themselves in special relationships with them.

One of the most common responses from people was that often they had not talked about how they felt because it is not a thing that one readily admits to. It is common to talk about someone's relationship to a special house or even their attachment to their car, but a tree - well it could sound a bit weird. But talk they did, children, cool teenagers, sports fans, families, mothers and fathers, the bereaved, the religious, the rough-as-guts, the rednecks and farmers, the surfies, even the wood-choppers. Absent from the list are ferals, hippies and new-agers, artists, nurserymen and truck drivers. Solness perhaps reckoned we would know their views already.

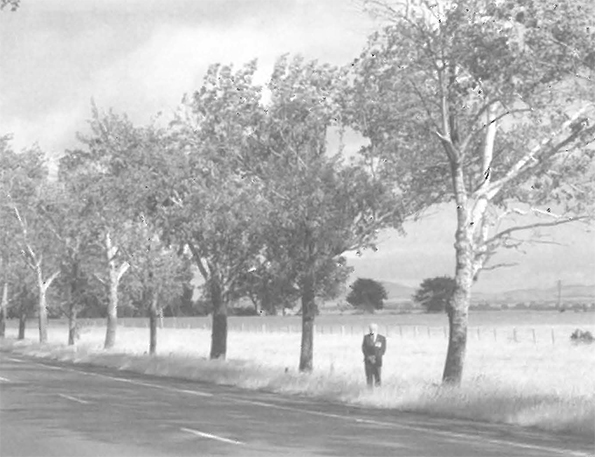

The book is divided into chapters according to the ways trees have been used in the culture. Birth Trees are the trees where babies used to be born not so long ago. Neville Bonner was born under a tree on the Tweed River, and most rural Aboriginal people over the age of 35 would know about the 'hospital tree' in their community. In white society the rituals around marriage and birth include weddings and christenings commonly performed with a grand old tree presiding serenely above. The Urban Tree is the one most familiar to most Australians, and Solness captures nicely the ongoing tension between trees and bureaucracy in the form of town planners and between trees and profit in the form of developers.

In the suburbs the fence-line battles between tree-loving and tree-hating neighbours are legion and sadly will strike a chord with many readers. Other chapters are about Meeting Trees, Historic Trees, Rural Trees, Extraordinary Trees, Campaign Trees, and so on. The saga of the Red Tree as described by John Smith in this issue (page 62) is told powerfully by the photograph itself (see page 10 this issue).

Throughout the book there is a meshing between the text and the pictures in which each enhances the other to a remarkable extent. At first sight this looks like a picture book with some stories; its genius is that it reveals a side of everyday life in modern Australia which is totally unexpected. Take hope, tree lovers - there are more out there like you than you may know!