Over the past six months AGWA has hosted a series of cutting-edge exhibitions exploring the socio-historic and psychological nuances of the spaces we occupy during our lives. The first was Nicola Kaye's installation, Facade and histories; as part of the Perth International Arts Festival, curators Gary Dufour, Trevor Smith and Tom Mulcaire brought the works of 14 international artists to Perth with home. Expressed through many of these works are concerns such as the importance of place to cultural identity and the need to nurture and respect both each other and the environment. My overwhelming impression of this exciting exhibition was of the tenderness with which many of the artists dealt with the issues of 'home'. This was due, in part, to many of the works being based on video or slide projection, flickering ephemeral images softly discreet on wall or screen. But also there is a tacit acknowledgment in most of the works that the inter-relationships between humans and their relationships with the world around them is extremely fragile. Lucy Orta's strangely enigmatic tent installation, Life Nexus Village Fete (1999), out of place in the gallery, is extraordinarily soft-edged and organic, oozing across the marble floor, a structured shelter raising largely ignored issues of social concern in relation to dominant liberal ideologies of individualism.

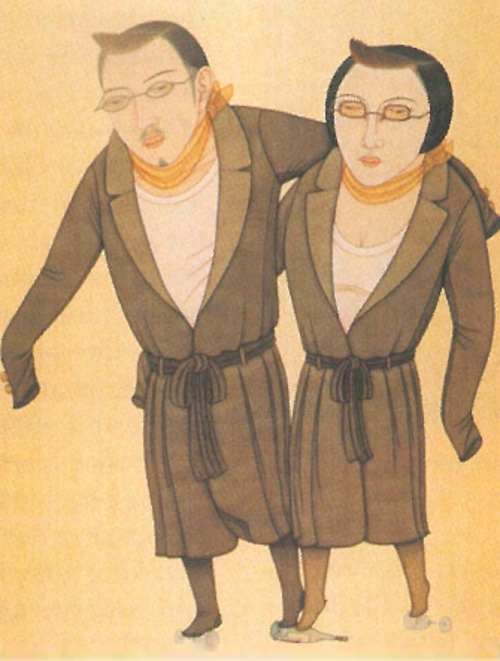

David Goldblatt, whose photographs Structures (1998) explore the ideological constructions of his South African home culture, shifts his focus to Wittenoom in Western Australia in a further series of images (1999). These document sites where government policies have indelibly marked both the landscape and its inhabitants. This concern with the land is reiterated in Matthew Ngui's Saltbush: Blue Heeler/Kookaburra (2000) and Our Landscape (1998). In this mixed media installation I observed myself observing the projection of a sketch of a blue heeler, quintessential icon of the Australian bush and masculinity. But here Ngui's collaborative work, combining children's sketches, plants and plywood, reminds us of the fragility of this environment. This work spills across the gallery floor to the base of a cabinet displaying eighteenth and nineteenth century ceramics, ('Nature and Fantasy' states the didactic), from the Gallery's collection. The juxtaposition reminds us that nature, the bush, a powerful cultural myth in contemporary Australian society, is under siege and in danger of becoming simply a fantasy. The land, seemingly so vital to every Australian's sense of identity and marker of home, is slowly being destroyed.

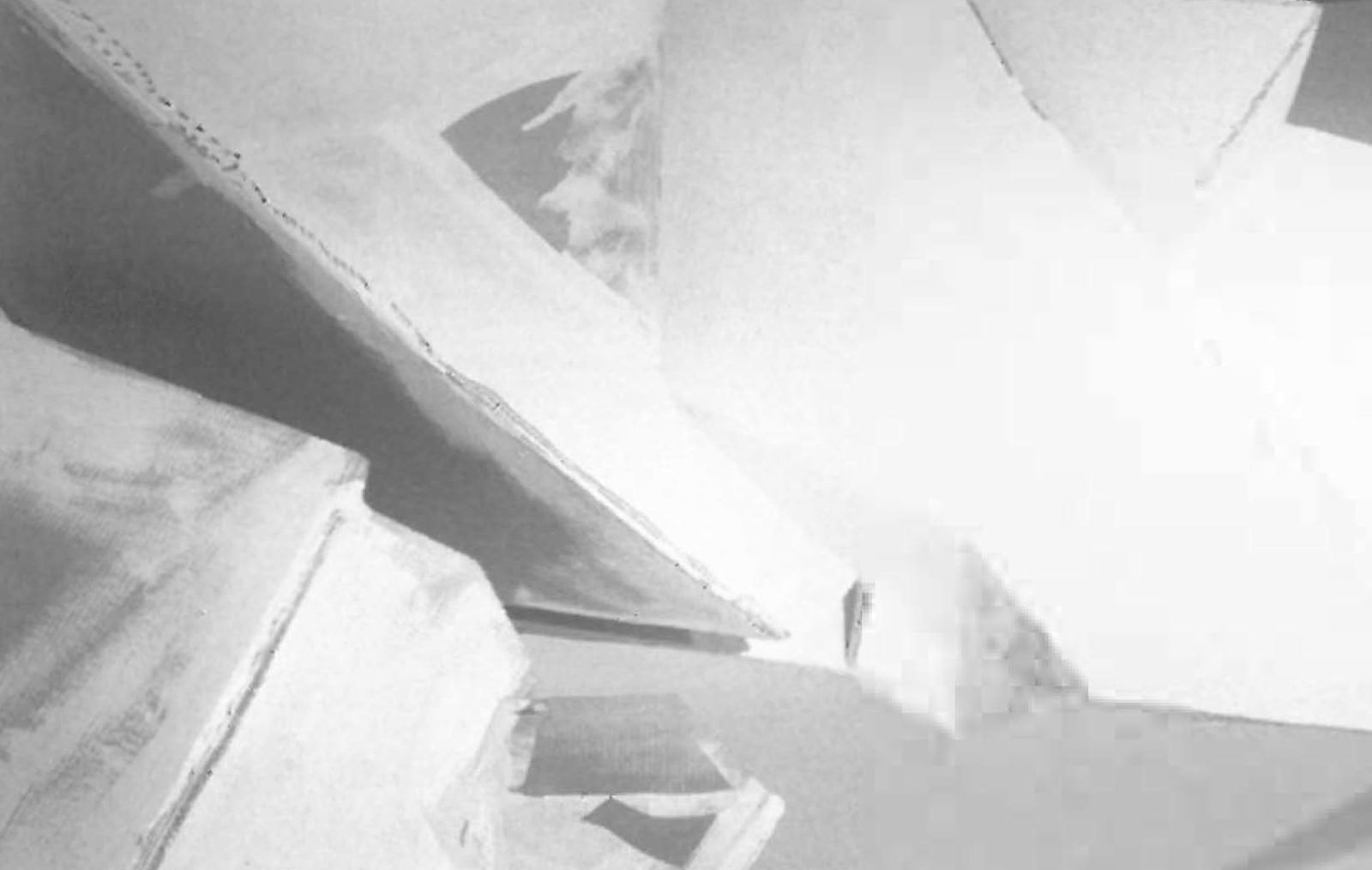

In Rodney Glick's installation, Mountain (2000) painted cardboard reconstructs the sharp angles and crevices of a mountain. Enjoyable and evocative, it also speaks of mountains of junk and refuse. Cardboard is a disposable item in our consumer society. From its protective packaging we construct our homes, filling our domestic spaces with a range of luxury items, fridges, washing machines, televisions, computers etc. At the other extreme those displaced by our society often shelter in cardboard. So this eloquent mountain speaks of both home and homelessness, domestic and public spaces.

The slippage between private/public recurs in Annelies Strba's Shades of Time 2 (1999), a haunting triple slide projection. Family photographs capture mother and daughter over the years in a shifting kaleidoscope of images that challenge the viewer to construct a narrative and yet constantly deny that possibility. Accompanied by a rhythmic and hypnotic sound track these slides are brief glimpses across time and generations. Images, including what eventually become familiar items, such as pieces of furniture, pets and the 'family face' recur, interspersed with strangely anonymous buildings and gardens. These fragmented family memories speak of home as a place of histories, of personal stories, poignant moments remembering the sleep of young children, beloved pets and then the brutal, impersonal public spaces of industrial cities. The intimacy of Strba's images of kin within bedroom, bathroom or kitchen, that ultimate domestic space, sit uncomfortably next to idealised landscapes and gardens. Are these holiday snaps, we wonder? Did these women and children escape the confinement of the small apartment and familiar kitchen furniture?

projection. Courtesy the artist.

This exhibition requires time to both observe and absorb. That 'home' is a fiction is a constantly explored theme here. We understand ourselves through memories of peoples and places. Thus the clearly recognised importance of place, the environment or land, to our socio-psychic well-being is reiterated from Cape Town to Kellerberrin, from Perth to Vancouver, and Igloolik to Paris.