Irene Briant has always been adept at making apparently simple materials and forms convey complex ideas. Her arresting installation draws the viewer into a new voyage of discovery: a journey to the Antipodes in striking images through which we re-view early European scientific exploration of Australia. Briant manages to make this re-seeing ironic, as the title suggests, but at the same time witty, rueful, postcolonially serious, and full of generous wonder at these travellers and their beautiful, strange illustrations.

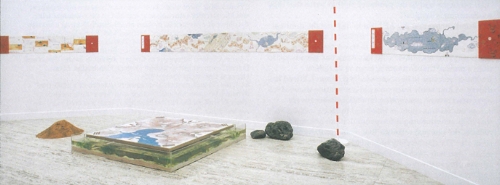

At one end of the gallery three pieces, Terra Australis Incognita, Trellis and Mirrors of the Imagination bring the Northern hemisphere of Napoleonic Europe vividly to life, its gaze turned towards the mysterious south. Terra Australis Incognita has four gold discs mounted at eye-level on slender stands which appear, from the viewer's side, to be plain gold, but on each reverse is an exquisite circular painting, a miniature of distant coast and sky as it would appear from the sea. As one walks past, these are reflected in four gold 'mirrors' (shining gold plastic plates) mounted on the wall. The effect is intermittent glimpses of a far-off landscape seen through a telescope - or through the mind's eye in Europe.

Trellis brings to mind the ornate formal gardens of the eighteenth century with their grand spaces and their trompe l'oeil manipulation of perspective. Here Briant hints at the distortions, deliberate and otherwise, which pervade human perception. Mirrors of the Imagination extends this idea. Fourteen 'mirrors' arranged in a long formal pattern on the wall suggest the gilded artifice of the palaces and courts where these voyages originated, where Baroque and Romantic frames of reference influenced imaginings of Australia. Gold paper plates could have been risky. In Briant's hands they are compelling, utterly convincing as the sign for an aristocratic age and a particular system of values.

Moving towards the other end of the gallery we confront images of the south. Birds, animals, a woman, as seen by early illustrators, but strikingly transformed by Briant to offer new layers of thought. In her three-part piece Hunter's Parrot she takes the bird off the illustrated page into three dimensions and then back into two, as its image might pass from one form to another, one viewer to another. Finally, it becomes a Magritte bird, less bird than sky, dramatically seen because not seen clearly, but also wittily suggesting the influence of artistic styles on perception and illustration. Briant repaints Nicholas Martin Petit's Woman of Bruny Island life-size on a banner of gold gauze and the Aboriginal woman becomes confrontingly, poignantly real in spite of the original drawing's distortions. The secret 'behind the arras' is a dark shadow on the wall.

Treasury makes explicit the questions of value which glitter throughout the installation. The title leads us to expect heaps of gold, but here are ten gold plates on a row of wall shelves, like the treasuries of Europe in which reliquaries contain sacred items such as St Peter's fingerbone, or a sliver of the True Cross. Each plate in Briant's Antipodean treasury contains a sacred relic too; a suggestive shell necklace, a snakeskin, animal bones, nuggets of seedhusks. They are familiar but weird because each has been gilded - perhaps the only way, Briant implies, these precious relics can be appreciated by 'civilised' values, by those who voyaged in search of more recognisable treasure.

Walking around the installation one circumnavigates the superbly beautiful title piece The Same Sky. Central both physically and conceptually, it draws the individual pieces into a whole. A large oval painting of the sky is mounted on the ceiling above a formal garden pond constructed in layers of gauze, each layer offering images which superimpose on each other; the sky reflected, a migratory pattern of flying birds, glimpses of a map, where continents have coastlines but also man-made lines of division. Below again, Lesueur's starfish. In this piece, the binary divisions so dear to the new sciences of the Enlightenment emerge only to be re-evaluated.

Art/nature, art/science, real/imagined, north/south, surface/depth are demonstrated but shown to be arbitrary human divisions. In this beautiful and challenging installation Briant seems to make a visual statement of optimism: perhaps we do not have to choose between Europe and Australia. The world is one, each individual who loves both hemispheres brings the two together. Mind can jump space at the speed of sight.